Review by Des Cowley.

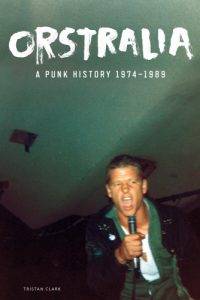

Orstralia: A Punk History 1974-1989 By Tristan Clark (PM Press, p/b)

There are those who believe punk music died off in the early ‘80s, having morphed into a range of user-friendly styles, from New Wave to New Romantics. Others argue differently, convinced it just went underground, providing succour to subsequent genres: hardcore, alternative, thrash metal, grunge.

Author Tristan Clark is an advocate of the latter school of thought. He has no truck with those who consider the Clash’s 1982 single ‘Rock the Casbah’, a remarkably snappy number that roared up the charts, spelt the demise of punk, proof it had gone mainstream.

Down under, similar currents were at play. By the early ‘80s, the embryonic energy and mayhem of Australian punk had metamorphosed into an assortment of bands familiar to us today: the Birthday Party, The Church, Models, the Moodists, Laughing Clowns. But at the same time, according to Clark, the spirit of punk thrived, typified by a new, aggressive sound that took its lead from US hardcore: bands like Sick Things, Civil Dissident, Depression, Mad Flowers.

Clark’s unwavering belief in the enduring vitality of punk is given full rein in Orstralia: A Punk History, covering the years 1974-1989 (a second volume covering 1990-1999 is slated for release shortly). Christening his book an ‘oral history’, it draws from over 130 interviews.

Clark’s unwavering belief in the enduring vitality of punk is given full rein in Orstralia: A Punk History, covering the years 1974-1989 (a second volume covering 1990-1999 is slated for release shortly). Christening his book an ‘oral history’, it draws from over 130 interviews.

While it’s customary to associate Australian punk with the likes of the Saints or Radio Birdman, those bands are just the tip of a very large iceberg. Clark is just as eager to document little-known bands, aiming to dig a little deeper, probe the scene from bottom up, celebrating the renowned and the trivial, the eminent and the unknown.

One of the enigmas of punk is how it exploded globally near simultaneously, eons before social media made such occurrences the norm. When it burst in Australia, Brisbane was ground zero. With its repressive politics and police surveillance, it most closely resembled the UK scene, where legions of disaffected youth spawned the Sex Pistols, the Buzzcocks, the Slits, the Clash, and countless others.

The fact that you could play this music with the barest minimum of musical competency made it attractive to any sixteen-year-old with a guitar or set of drums. Bands sprang up all over the land, many lasting no longer than a season, often playing no more than a handful of gigs. The most successful might have managed a 7” single, while the rest were relegated to memory, now given a fleeting second life in Clark’s account.

Because punk’s ethos was antithetical to established hierarchies, Clark has chosen to organise his account democratically, dividing it by geographic locale as distinct from more obvious classifiers like fame or success. Clark begins with Qld (Brisbane, Ipswich, Rockhampton, Townsville), before moving south to Sydney, Canberra, Melbourne, and further afield to Hobart, Adelaide, Darwin, Perth. If you’d asked me to name a Rockhampton punk band before I read Clark’s book, I’d have drawn a blank.

While the Saint’s ‘(I’m) Stranded’ is generally heralded as our first local punk single, the fact that the band relocated to London by May 1977 meant they had little to do with subsequent events. By then, Brisbane was swarming with punk bands: the Leftovers, Survivors, Razar, Disposable Fits, all drawing from a mish-mash of UK and US punk, filtered through echoey strains of the Velvet Underground, the Stooges, and MC5. By 1979-1980, many had relocated to Sydney, a move accelerated by continuing police harassment, and a rampant drug culture that was taking a heavy toll.

Down south, the more liberal culture of Sydney was dominated by Radio Birdman, who were soon joined by the Psychosurgeons, the Scabs, Filth, Kamikaze Kids, and others. In those pre-internet days, music was a local phenomenon, emerging out of its own specific determinants. Melbourne boasted a more eclectic and arthouse scene, reflected in bands like the Primitive Calculators, best captured in Richard Lowenstein’s 2009 documentary We’re Living on Dog Food.

Punk was very much a male pursuit, though there were exceptions. Gash guitarist Liz remembers going to Cold Chisel and Rose Tattoo gigs, and thinking: “Why aren’t there more women doing that?”. Lead singer with Def FX, Fiona Horne, recounts a music scene rampant with drug use and sexism. Diversity was also in short supply, though Sydney band the Hard-Ons, a trio hailing from then Yugoslavia, South Korea, and Sri Lanka, would prove a rare multicultural success story.

One of the consistent threads of Clark’s history is the violent behaviour rife at punk gigs. Was it really that bad? Or is that how people chiefly remember it? Clark’s reliance on oral testimony comes with obvious pitfalls, given those involved are retrieving memories decades old. Stories, after all, grow with age. But the plus side, we are hearing first-hand from the proverbial horse’s mouth.

Out of the maelstrom of little bands would emerge figures like Kim Salmon, Dave Graney, Clare Moore, Dave Warner, alongside founding members of the Hoodoo Gurus, and Triffids. Others washed up elsewhere. After Jeff Fatt and Anthony Field left the Cockroaches, they formed the Wiggles, a far cry from their punk beginnings. For some, it is all distant memory, a brief wild precursor to subsequent lives as teachers and public servants.

The 35-or-so photos included give a feel for the period. Rather than Vivien Westwood fashion statements – all leather, safety pins, glamour, and spiky hair – there is a refreshing lack of pretentiousness in the Australian scene: long hair still abounds, singlets and sloppy joes, and the club interiors are suitably drecky. This was Australia of the late seventies, for anyone who can remember.

I suspect anyone unacquainted with the underground punk scene in Australia is destined to find Clark’s book a slog. But that’s not his audience. Far easier to acknowledge his achievement: to have stitched together a patchwork narrative from first-hand accounts, highlighting that punk music in this country far outlived its explosive origins nearly half-a-century ago.