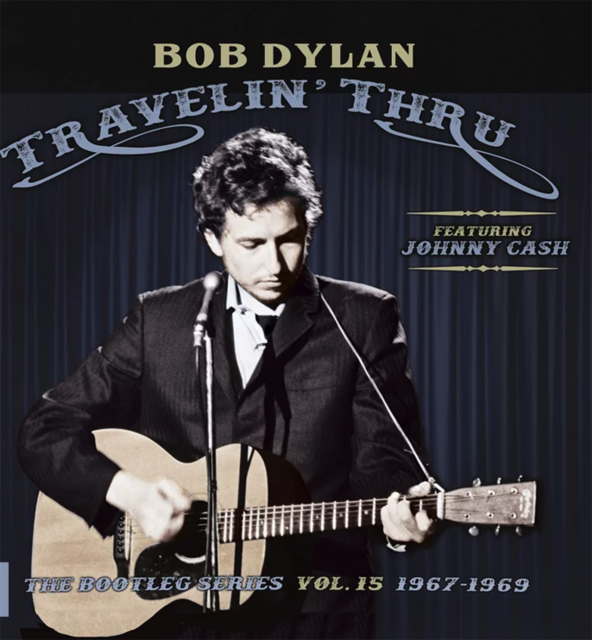

TRAVELIN’ THROUGH 1967-1969: THE BOOTLEG SERIES, VOL.15

By Michael Goldberg.

Bob Dylan had vanished. In the midst of a 1966 world tour in which he played his recent rock music with the future members of the Band, while taking a break in Woodstock, New York in July of that year, he fell off his motorcycle, sustaining injuries to his neck. I was 13 at the time, a big fan of Dylan’s rock sound, but I don’t recall knowing about the accident back then. Nor did I know it when Dylan began working with his backing musicians, recording the infamous Basement Tapes.

What I eventually did know, when I heard John Wesley Harding in December 1967, was that Dylan had changed, yet again. He had abandoned rock music for a whole different sound. And what struck me as particularly odd was that while most of that album sounded like a throwback, hillbilly mountain music, two songs at the end of the album – songs that I thought seemed so out of character they belonged on a different record – were country. Those two songs – “Down Along the Cove” and “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” – were unlike anything else Dylan had recorded that I had heard. Country? How could hipster Bob Dylan be into country? My 13-year-old self thought country was lame, man.

After I got over the shock, I realized that I really dug those songs, and thus I had to confront my anti-country prejudice. Before long the Byrds would release Sweetheart of the Rodeo and the Stones would start including country songs on their albums. Country-rock would become a new genre.

As we all know, Dylan followed up John Wesley Harding with Nashville Skyline, an entire album of country music. The shocker on that one was Dylan’s voice. He’d traded in the nasal sarcasm typified by “Like A Rolling Stone” for a smooth baritone croon. Prepped for this new change by those two songs at the end of John Wesley Harding, I immediately embraced Nashville Skyline and became an ardent defender of Dylan’s country sound. Leading off that album was a marvelous duet with Johnny Cash on an old Dylan song, “Girl From the North Country.”

Dylan had first met Johnny Cash at 1964’s Newport Folk Festival, and they were mutual fans. In his book, Cash: The Autobiography, Johnny Cash wrote, “I had a portable record player that I’d take along on the road And I’d put on [The] Freewheelin’ [Bob Dylan] backstage, then go out and do my show, then listen again as soon as I came off. After a while I wrote Bob a letter telling him how much of a fan I was. He wrote back almost immediately, saying he’d been following my music since [1956’s] ‘I Walk the Line,’ and so we began a correspondence.”

Following Cash’s death in 2003, Dylan wrote, “In plain terms, Johnny was and is the North Star, you could guide your ship by him – the greatest of the greats then and now. Truly he is what the land and country is all about, the heart and soul of it personified and what it means to be here; and he said it all in plain English. I think we can have recollections of him but we can’t define him any more than we can define a fountain of truth, light and beauty. If we want to know what it means to be mortal, we need look no further than the Man in Black. Blessed with a profound imagination, he used the gift to express all the various causes of the human soul.”

In his 2004 autobiography, Chronicles: Volume One, Dylan wrote, “Johnny didn’t have a piercing yell, but ten thousand years of culture fell from him. He could have been a cave dweller. He sounds like he’s at the edge of the fire, or in deep snow, or in a ghostly forest, the coolness of conscious obvious strength, full tilt and vibrant with danger.”

Dylan’s new three-CD set, Travelin’ Thru (Featuring Johnny Cash): The Bootleg Series Vol. 15, compiles alternative takes and outtakes from John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline, includes three recordings Dylan made with Earl Scruggs (“East Virginia Blues,” “To Be Alone With You” and “Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance”) and three songs Dylan sang on “The Johnny Cash Show” including his duet with Cash on “Girl From the North Country,” but the heart of the set are 25 songs and partial songs in which Dylan duets with Cash, all of which recorded during a two-day session in Nashville that took place on February 17 and 18, 1969 in Columbia’s Studio A. Dylan was in Nashville recording Nashville Skyline at the time.

The songs were recorded for a proposed Dylan-Cash duet album, but at least a third session was needed and that never happened; until now, the only recording from the sessions officially released was “Girl From the North Country.”

I love these recordings. Others have complained that Dylan and Cash’s voices don’t work well together. I totally disagree, and if you dug “Girl From the North Country,” I think you’ll agree with me.

A highlight here is “Wanted Man,” which Dylan likely wrote with Cash in mind, and which Cash played on February 24, 1969 at San Quentin State Prison in California; “Wanted Man” led off the album recorded during that show.

Dueting on “Wanted Man” in Nashville eight days before the San Quentin date, Dylan and Cash were in a great mood. The premise of the song is that the “Wanted Man,” is wanted everywhere for breaking the law (“Wanted man in Indiana/ Wanted man in Ohio/ Wanted man in Texarcana/ Wanted man in Mexico/…Wherever you may look tonight/ You may see this wanted man.”). He’s also wanted by a bunch of women for two-timing them, or leaving them behind, or both (Wanted man by Lucy Watson/ Wanted man by Jeannie Brown/ Wanted man by Nellie Johnson…)”. As they sing the song, Dylan forgets some of the lyrics, and then towards the end Cash starts adlibbing cities, finally throwing out “Hibbing” (where Dylan grew up) with Dylan laughing.

The session band includes an original member of Cash’s first band, the Tennessee Two (Marshall Grant, bass) and two musicians who later played with Cash (drummer W.S. Holland, 1960 and guitarist Bob Wootton, 1968). Also on guitar, the great Carl Perkins, whose song “Matchbox” (recorded by the Beatles in 1964) is covered here.

There are two beautiful versions of “I Still Miss Someone,” the song Dylan and Cash sing in the unreleased Dylan film, “Eat the Document.” The two men also pay tribute to Jimmie Rodgers with “Jimmie Rodgers Medley No. 1” and “Jimmie Rodgers Medley No. 2,” and sing ”Careless Love,” “Guess Things Happen That Way,” “Ring of Fire” and others.

Most of the songs that Dylan and Cash sing together are classics. They are songs that some of us grew up on (“Matchbox,” “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright,” “Big River,” “One Too Many Mornings,” “I Walk the Line,” “This Train Is Bound For Glory,” “Mystery Train”), and they’re in the history books.

The spirit of these recordings is a couple guys, clearly equals, sitting around having a ball jamming on some of their favorites – two of the world’s greatest musicians having the best of times.

It never happened again. This was the only time Dylan and Cash collaborated in the studio. If that means something to you, than you need to hear these sessions, and if you’ve gotten this far in this essay, I’d say it does mean something to you.

Michael Goldberg, a former Rolling Stone Senior Writer and founder of the original Addicted To Noise online magazine, is author of three rock & roll novels including 2016’s “Untitled.”