By Jonathan Alley

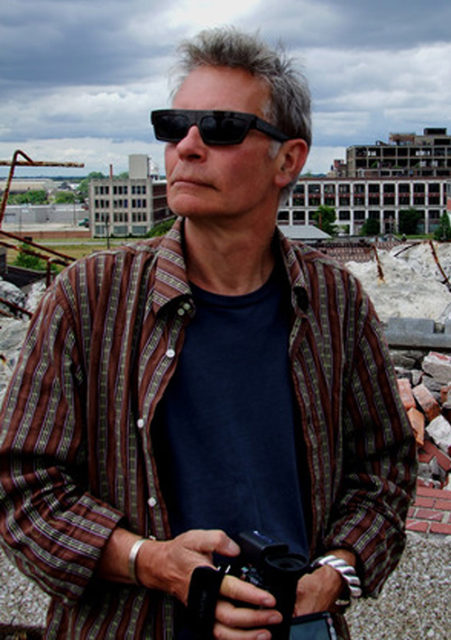

The British director Julien Temple specialises in bringing the story of wayward, controversial and often brilliant musical figures to vivid life on screen. The Sex Pistols, The Clash’s Joe Strummer, ground zero pub-rockers Dr Feelgood, and that band’s original guitarist Wilko Johnson have all found themselves in the cinematic crosshairs of the maverick British director’s self-described “mutant pieces of cinema”: he firmly eschews the term ‘documentary’.

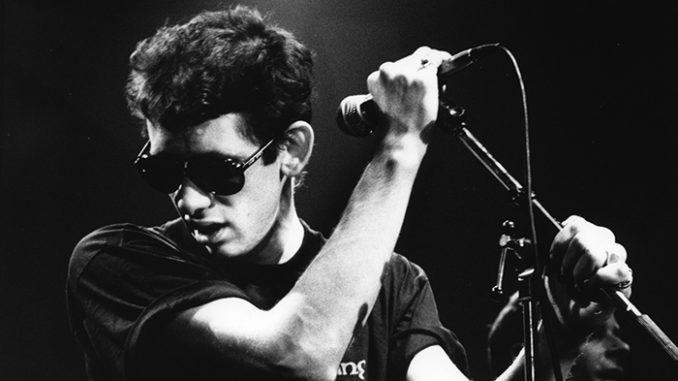

Temple’s latest subject is Irish songwriter, poet and all-round scoundrel Shane McGowan, best known for fronting The Pogues. Crock of Gold: A Few Rounds with Shane McGowan faces the not-inconsiderable-challenge of extracting some lucid sense from the legendarily alcohol-sodden Irishman, but — with subtitles provided – a far sharper, and more complex picture of McGowan is allowed to emerge.

While McGowan is inevitably prematurely aged and diminished by his addiction, his mental faculties are far more intact than most might realise. Intriguingly, Temple has left the interviews — really more a round of filmed informal chats — to McGowan’s friends and contemporaries; figures like Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie, the now infamous Johnny Depp (the film’s co-producer, whom McGowan effortlessly barbs with a single riposte that destroys the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise), and even Sinn Fein elder Gerry Adams.

“Your songs broadened our sense of ourselves. Redemption, sorrow, the ordinary person’s story,” says Adams at one point. McGowan hardly seems to register such praise in the moment, but elsewhere in the film — as a devout Catholic — speak of God’s plan for this young man to reignite the national music of Ireland. While McGowan — inevitably and effortlessly— looms over Temple’s film as its largest character, the other major player is not a person, but Ireland itself, in both its traditional and modern senses. Temple uses animation and archive footage to illustrate the Ireland of yesteryear McGowan that shaped his formative landscape. The emerald fields of green, the Guinness and whiskey-soaked friends and neighbours, the songs, the poems, the history. Modern Ireland, in McGowan’s world, is formed and inevitably given its contemporary shape, by yester-year. The sins of the past create the now and the future. It’s when this is given some musical expression that Temple’s film is at its strongest. The Pogues themselves though, remain firmly represented by the archives.

“We did ask the guys in The Pogues , but they also said ‘no’ “ Temple told Melbourne’s Triple R FM in 2020, “and in a way I think that’s better; this is Shane’s story and it was better to get an undiluted view of his childhood, what shaped him, the clear memory the imagery around his upbringing, the poetry, the land, and the journey onward and since, if you bring in the story of the band, as opposed to Shane’s own story, you’d get side-tracked”.

In his conversation with Adams, McGowan relates the writing of The Pogues song The Bones. As children, McGowan and a friend cycled through the local sand dunes. Their two-wheeled travels upset the thin and barely effective cover of the sand, exposing the skeletal remains of hundreds of local people buried on the beach during ‘the great starvation'(both Adams and McGowan refuse to refer it as ‘the famine’, as they see it in overtly political terms, as an avoidable disaster). The recreation of this innocent afternoon trip, under-scored by the music of The Pogues, brings this dreadful period roaring back to present day.

Indeed, the other driver — apart from alcohol and poetry — of this quintessentially Irish story is, almost inevitably, religion. McGowan’s fire and brimstone Catholic aunt would offer the young boy alcohol if he renounced The Devil; the young lad was only too happy to give Satan the boot for a drop and remains steadfast in his view that drinking is not a sin.

McGowan’s hell-raising is certainly covered unflinchingly: the animated sequence of his hallucination that dead Maori warriors are commanding him to paint his entire New Zealand hotel room blue (an order to McGowan happily acquiesced) is one uproarious highlight.

But, Temple’s film successfully makes a case that McGowan’s major contribution to music transcends his substance-fuelled adventures: McGowan’s goal was to return Irish lyricism and traditional music to its rightful place. Temple’s film, correctly, makes the case that The Pogues — particularly via the albums Rum, Sodomy and the Lash and If I Should Fall from Grace with God, did just that.

Interviewed in a more conventional sense are McGowan’s family — his parents largely via archive — but his sister, the Irish journalist Sinead McGowan, emerges in the piece as a sharp and unwavering observer of all the extreme elements, good and bad, that have shaped her brother.

“He went away …. and didn’t come back. Not the Shane that I knew. Then doctors told me he had six months to live,” she relates when speaking of McGowan’s mental and physical state at the height of The Pogues’ commercial success. This particular medical advice was provided thirty years ago now.

The mystery of what’s kept McGowan alive may not be answerable: however, Temple’s film makes the case that the artist remains just ahead of the legend, albeit by a whisker.

“Shane won’t tell me what he thinks of the film…. I’m never going to get that out of him…” Temple told Triple R “but I do know he and Gerry Adams went to see it together, in a cinema, for a private screening. According to Gerry, Shane was in tears”.