In his new book, Hollywood Eden, Joel Selvin tells the compelling story of the beginnings of the Southern California rock scene.

By Michael Goldberg.

The Beach Boys “Good Vibrations” may be the greatest rock recording every made, and an excellent new book, Hollywood Eden: Electric Guitars, Fast Cars, and the Myth of the California Paradise, written by author/rock critic Joel Selvin, details how a new Hollywood-centered rock scene that began in the late ’50s led to Brian Wilson’s 1966 masterpiece.

Selvin’s book is much more than the story of “Good Vibrations.” It’s a fascinating, at times thrilling, at times heartbreaking, social history of a scene that created a new California youth culture: as the songs of Jan & Dean, Dick Dale, the Beach Boys and others topped the pop charts, kids across the country came to know southern California as home to sun, surf and “two girls for every boy,” as Jan and Dean sang in their 1963 number one hit, “Surf City. From Selvin’s opening sentence I was hooked; I read the book straight through over about two days, barely able to put it down for meals and sleep.

To tell his story, Selvin follows a number of essential characters, starting when most of them were still teenagers and attending one of five Los Angeles area high schools. Included are Jan Berry, Dean Torrence, singer/songwriter Jill Gibson (who became Berry’s girlfriend and co-wrote songs with her lover), drummer Sandy Nelson (who played on Phil Spector’s “To Know Him is To Love Him” and scored a #4 hit with his own song, “Teen Beat”), Nancy Sinatra, producer/manager Kim Fowley, Phil Spector, Brian Wilson, producer Lou Adler, surfer Kathy “Gidget” Kohner, saxophonist Steve Douglas and singer/songwriter Phil (P.F.) Sloan, best known for writing the #1 1965 U.S. hit, “Eve of Destruction.”

As Selvin tells it, the L.A. rock scene began in the locker room showers of University High in the fall of 1957 when a naked Jan Berry, blonde-haired and “movie star handsome,” walked in and began singing the Silhouettes current hit, “Get a Job,” immediately joined by Dean Torrence and perhaps a dozen football players who had just finished practice. Berry became obsessed with rock ‘n’ roll and turned his parents garage into a rehearsal and recording studio where, using two used Ampex tape recorders that his electrical-engineer father had bought, he begin cutting demos of the songs he was writing.

In the beginning, Selvin makes clear, Berry and many of the other young men and women who would develop or inspire L.A. rock were naïve, clueless to the sometimes dark ways of the music business; their innocence would soon fade. By June of 1958, Jan and Dean had scored their first Top 10 hit with the Joe Lubin-produced “Jennie Lee,” a song credited to Jan and his friend Arnie Ginsburg, written after Dean, Ginsburg and some of their friends saw a stripper named Jennie Lee, the “Bazoom Girl,” do her thing at the New Follies Burlesk on Main Street in downtown L.A.

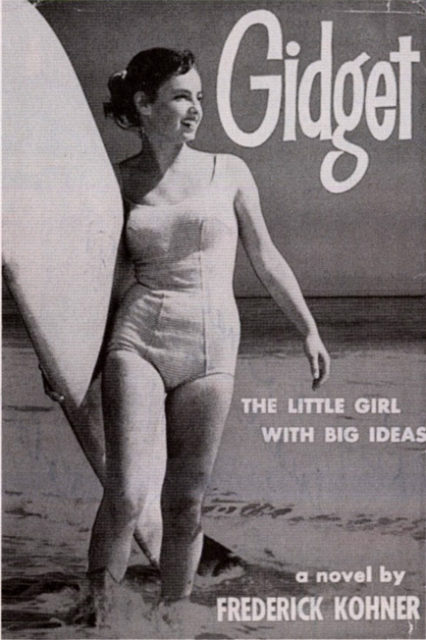

A year earlier, in June of 1956, University High School student Kathy Kohner, who was hanging out at Malibu Pier watching a handful of surfers ride the waves, decided she wanted to learn to surf. At the time, surfing was an obscure sport; at Malibu Pier, it was practiced by “a group of determined outcasts who lived in a palm-frond-and-driftwood shack on the beach,” Selvin writes. The surfers there gave Kohner a nickname; “they called her the girl midget—Gidget.”

Kohner kept a diary and wrote about her summer of surfing. By the fall she wanted to write a book about her exploits but when she spoke to her screenwriter father about it, after reading her diary he told her he would write it. His book, “Gidget: The Little Girl with Big Ideas,” was published in October 1957 and as Selvin writes, the book “introduced the world to the California paradise and the nascent surf culture.”

Rather than write a traditional non-fiction book attributing everything stated to his sources and quoting all of those sources frequently, Selvin has written his book as if it were a novel, only including quotes when they are part of a scene he is describing. Confident in his research, Selvin’s approach brings the Southern California environment where the action takes place and his idiosyncratic characters to life; he puts the reader in the room with them as the action unfolds. Selvin suggested during a recent radio interview, Hollywood Eden would translate into a wonderful multi-episode TV series and he’s right. As much as the book is about the musical successes and failures of the artists, producers, session musicians and other characters Selvin writes about, it’s also about their personal lives, and how the way they lived profoundly impacted their professional lives, and thus, the history or popular music.

Selvin writes eloquently about Phil Spector, and the “Wall of Sound” producer’s successes: successes that came to an abrupt halt in 1966 with the release of what Spector thought was his greatest recording, Ike and Tina Turner’s “River Deep Mountain High.” Spector never recovered from the failure of that song to become a hit in the U.S. Selvin also covers the rise and fall of the Mamas and the Papas, the reinvention of Nancy Sinatra with “These Boots Are Made for Walkin’,” and much more.

And then there’s “Good Vibrations.” Brian Wilson tried LSD for the first time in April of 1965; he believed acid brought out his insecurities, which showed up in many of the brilliant songs he wrote or co-wrote for Pet Sounds, the album he told his wife would be “the greatest rock album ever made!” He was also smoking weed at the time and said it added to his creativity.

Wilson, a major fan of Phil Spector’s recordings, began work on “Good Vibrations” in early 1966, a few months after he’d begun working on the songs that would comprise Pet Sounds. Selvin writes that Wilson “had first composed this new piece of music … on his third LSD trip, an ecstatic and enlightening spiritual experience for Brian.” The first recording session for “Good Vibrations” took place on February 17 at Gold Star, the studio where Phil Spector had recorded many of his epic Wall of Sound hits. Wilson and the session musicians he hired recorded twenty-six takes that night; the next night they recorded another 28 takes. Soon enough, Wilson decided the song wasn’t right for Pet Sounds, the album that would be the both the creative highlight of his career, and a commercial disaster. So, he put it aside.

On May 16, Pet Sounds was released. It peaked at #10 on the Billboard Top 200, but was considered a failure, which, along with the insecurity and paranoia that Wilson felt do to his continued use of LSD and other drugs, made him question whether “Good Vibrations” was good enough. “Brian envisioned the piece as his greatest work, a self-conscious masterpiece,” Selvin writes.

Over the next four months, Wilson divided his time between working on the never completed Smile album with his most recent writing partner, Van Dyke Parks, and working and reworking “Good Vibrations.” “After more than seven months, twenty-two sessions, and somewhere between six and ten finished versions of the song, Brian had spend more than $50,000 on the record, more than any single ever,” Selvin writes. “Good Vibrations” was released on October 10, 1966 and sold more than one hundred thousand copies a day during the first week, according to Selvin. “It was the biggest hit the Beach Boys ever had.” Sadly, the drugs Wilson was taking during ’65 and ’66 sent him on a downhill spiral and he never again equaled the creative work he did on Pet Sounds and “Good Vibrations.”

Selvin’s book concludes in 1966, when the early days of L.A. rock were over, and the next phase, which includes the folk-rock of the Byrds and the hard rock of the Doors, had begun. The ending of Hollywood Eden is bittersweet, and just as the book began with Jan Berry, so it concludes.

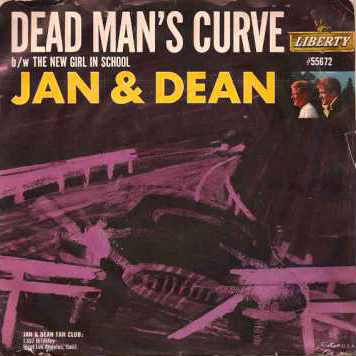

On April 12, 1966. Berry, who frequently drove too fast, was furious as he got into his Corvette Stingray. The U.S. was at war in Vietnam, and Berry had been drafted. He had just met with the draft board hoping to convince them to give him a deferment. The board hadn’t bought into his arguments. Taking the route he and Dean had sung about in “Dead Man’s Curve,” Berry eventually turned onto North Whittier and accelerated. A gardener, Mitsuru Ondo, was watching. Selvin writes, Ondo “saw the car waver slightly and strike the curb with its right rear wheel. The car flew out of control down the street until it smashed into the back of Ondo’s truck [near the intersection of Sunset Blvd. in Beverly Hills] and, as the sound of breaking glass and screeching metal tore through the air, shoved the truck another seventy feet down the street before coming to rest. Jan’s Stingray was crushed underneath the rear of Ondo’s pickup. Jan had smashed into the truck at something like eighty miles an hour. The fiberglass body of the Stingray exploded.”

Selvin writes that “after brain surgery at UCLA Medical Center, Berry was left in a deep coma.” Eventually he recovered from partial paralysis and brain damage. No longer “movie-star handsome,” Berry “looked beat up, his face swollen, his eyes dark, a tracheotomy scar across his neck.” By starting and ending his book with Berry, so young, so fearless in the beginning, so sad and pathetic by the end, the surf rock singer/songwriter is both a man and a symbol. By 1966 the Eden of the early Hollywood rock scene was done.

The final scene of the book shows us Berry sitting in a wheel chair in a Westwood diner as he emerges from his post-accident haze and recognizes someone sitting—in this case Joe Lubin, who had produced “Jennie Lee,” Jan and Dean’s first hit—for the first time. Jan and Dead would never have another hit, but at least Berry’s memory had returned.

Michael Goldberg, a former Rolling Stone Senior Writer and founder of the original Addicted To Noise online magazine, is author of three rock & roll novels including 2016’s “Untitled.”