The Whole World In a Song: An Interview with Critic Greil Marcus on Bob Dylan, His New Dylan Book, the Role of the Critic and Much More

By Michael Goldberg

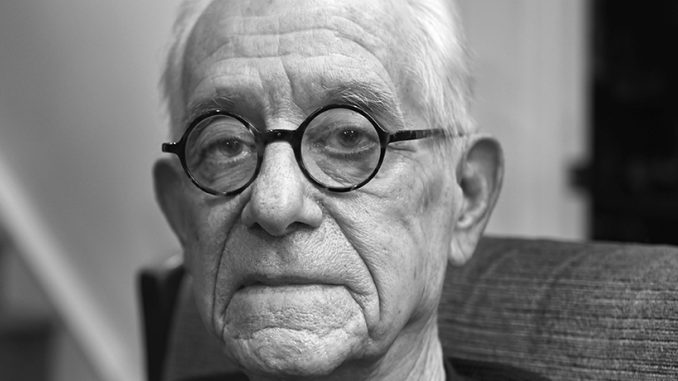

Greil Marcus writing or talking about Bob Dylan is the holy grail. He is the leading authority on Dylan, and the best known and most respected rock critic in the U.S. (and probably the world). His first in-depth book about rock music, Mystery Train (the title coming from one of Elvis’ Sun Records recordings), published in 1975, established him as a leading authority on rock music, and his stature has only grown since then.

David Cantwell wrote in a December 2015 profile of Marcus published in the New Yorker, that nearly as soon as Mystery Train was published it was “short-listed as ‘the best’ or ‘the finest’ or ‘most compelling’ book ever written about popular music…”

After the book was first published, Frank Rich wrote in the Village Voice, Mystery Train is determinedly and proudly in the tradition of such ground-breaking works of American cultural criticism as Leslie Fiedler’s Love and Death in the American Novel, D.H. Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature and F.O. Matthiessen’s American Renaissance (the first two of which Marcus draws from in his work); as his predecessors sought to understand Poe’s nightmares or the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock in terms of our most substantial national myths, so Marcus attempts to place such songs as Randy Newman’s “Sail Away,” The Band’s “Across the Great Divide,” and Elvis Presley’s early efforts for Sam Phillips at Sun Records into the same broad cultural context.”

Although Mystery Train might have seemed to some to be about a handful of musicians—Harmonica Frank, Robert Johnson, The Band, Sly Stone, Randy Newman and Elvis Presley—the book is about much more than that. As Marcus states in the intro, the book is “an attempt to broaden the context in which the music is heard; to deal with rock ’n’ roll not as youth culture, or counterculture, but simply as American culture. … [These musicians] share unique musical and public personalities, enough ambition to make even their failures interesting, and a lack of critical commentary extensive or committed enough to do their work justice. In their music and in their careers, they share a range and a depth that seem to crystalize naturally in visions and versions of America: its possibilities, limits, openings, traps. Their stories are hardly the whole story, but they can tell us how much the story matters.” This was the beginning of where Greil Marcus would go for the next 47 years, finding America, and so much more, within a handful of songs, sometimes a single song.

Born during the summer of 1945 in San Francisco, Marcus grew up in Menlo Park, a suburb south of the city; he attended U.C. Berkeley, where he earned an undergraduate degree in American studies. He saw Bob Dylan for the first time in 1963, when Joan Baez brought the determinedly scruffy singer/songwriter onstage at a show that took place in “a field in New Jersey.” One of the songs Dylan sang that day was “With God on Our Side” and, as Marcus told me during our interview, he was “absolutely stunned.” It was the beginning of an obsession with Dylan and his music.

In 1968 Marcus wrote a review of an album by the Who, and, unsolicited, sent it to Rolling Stone, the rock magazine that had begun a year earlier; two weeks later it was published in the record reviews section. Soon he was on-staff and spent six months as Rolling Stone’s record reviews editor; he lost the job due to a dispute with publisher/editor-in-chief Jann Wenner over Bob Dylan’s Self Portrait; Marcus infamously began his review of the album this way: “What is this shit?”

Over the years Marcus wrote for Creem, the Village Voice, New West, Artforum, Interview, the Wire, Salon, The Believerand many other publications including the New York Times and the New Yorker. He has written 19 books and edited another six. Perhaps his most remarkable book (and a favorite of mine) is Lipstick Traces, which he spent nine years researching and writing; as Andy Beckett wrote in The Independent, “Lipstick Traces began as a book about the Sex Pistols; then expanded crazily back in time to Paris in 1968, Dada in 1917, the French Revolution, and ultimately to libertarian heresies in the Middle Ages. Marcus found himself writing ‘a secret history of the 20th century,’ a search for the origins and story of the nihilistic impulse that the Sex Pistols had stumbled upon.”

Marcus wrote a monthly column, “Real Life Rock,” for New West magazine from 1978 to 1983; that column combined an essay with a top ten at the end. Three years later, Marcus was asked to take the top ten and turn it into a 700-word column for the Village Voice, which he titled, “Real Life Rock Top Ten.” The column “had room for anything,” Marcus wrote in his introduction to Real Life Rock, a book that collects every column he wrote from 1986 through September 2014 (a second book, More Real Life Rock, was published earlier this year), “music, movies, fiction, critical theory, ads, television shows, remarks overheard waiting in line, news items, contributions from correspondents… treating the column as a forum or a good site for gossip, or the everyday conversation it has always wanted to be.”

Over time, the “Real Life Rock Top Ten” moved to Salon, The Believer, Interview, Rolling Stone and some other publications. Most recently, Marcus wrote it for The Los Angeles Review of Books, where it was published until February 2022; he was about to move it to Substack when he became ill; he has been recovering for many months and the future of the column was up in the air when I spoke to him in mid-September.

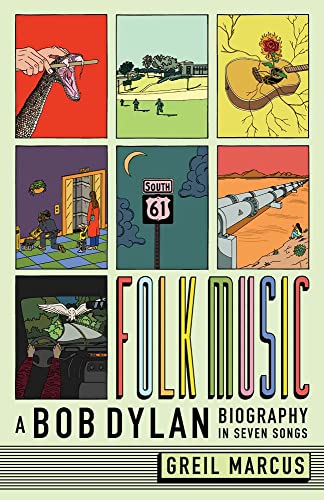

His most recent book, Folk Music: A Bob Dylan Biography in Seven Songs (Yale University Press), was published on October 1, 2022. It’s the fourth book Marcus has written about Dylan, the others being The Old Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes, Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads, and Bob Dylan by Greil Marcus: Writings, 1968-2010. Additionally, a third of his book Three Songs, Three Singers, Three Nations is devoted to Dylan’s “Ballad of Hollis Brown.”

Folk Music is unlike any other book about Bob Dylan, and other than Dylan’s own memoir, Chronicles, it gets as close as may be possible to who Dylan the singer, songwriter, recording artist and performer is, and what can be found within his recorded songs, and sometimes many different versions of the same song as performed in concert.

As Marcus discusses the seven songs of the book’s title, he turns up numerous details about Dylan including recordings that I was unaware of, and that you may be unaware of as well. For instance, he discusses the 31 live performances of “Jim Jones” that Dylan did during 1993 (which one of Marcus’ readers had burned onto three CDs and sent to him); how the way Dylan performs “Jim Jones” changes from night to night, and how he eventually finds his way deep into the song. “And then, on February 9, still in London, it’s all there,” Marcus writes. “Though in the previous nights the song could drag on for nearly seven minutes, here it’s barely five, yet it seems to unfold more slowly—and that’s because for the first time there is a sense of a story being told, of something present to unfold.”

One footnote explores a rehearsal session with Dylan, Keith Richards and Ron Wood that took place shortly before they performed at Live Aid in 1985. That session, which could be heard on YouTube at the time I wrote this, finds the three men jamming on “Ballad of Hollis Brown,” “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and the old Appalachian song, “Little Maggie.” They talk among themselves, apparently unhindered by any thought that their conversation and jam session would eventually be made public.

Marcus quotes the music critic Paul Nelson: “Dylan’s talent evoked such an intense degree of personal participation from both his admirers and detractors that he could not be permitted so much as a random action. Hungry for a sign, the world used to follow him around, just waiting for him to drop a cigarette butt. When he did they’d sift through the remains, looking for significance. The scary part is they’d find it—and it really would be significant.”

And then Marcus writes: “So, this is a book of cigarette butts.”

It’s also a book packed with often-novel ideas. Every page seems to reveal something new, a fresh way of considering Dylan or one of his songs, or a song he sang, or a song that influenced him.

In the “Jim Jones” chapter, Marcus tells us quite a bit about the folk singer/historian Mike Seeger (Pete Seeger’s brother) and how in the early ’60s Dylan tried for a while to play the old folk songs Seeger played as good as Seeger but decided that was pointless. “He [Mike Seeger] played them as good as it was possible to play them…” Marcus quotes Dylan writing in Chronicles. “The thought occurred to me that I’d have to write my own folk songs, ones Mike didn’t know.” And then Marcus writes: “And so he did; that is Bob Dylan’s practical biography. He rewrote the songbook and then the book took on a new shape and all the credited sources that might have been printed on the title page disappeared until only one was left…”

I’ve known Greil Marcus since the late ’70s, when he was writing for New West (and, at the request of an editor there to whom I had pitched a profile of the Flamin’ Groovies, I called him up to make sure he wasn’t planning to write about the Groovies; he wasn’t). Since then, we’ve stayed in occasional contact; I consider him a friend. He wrote the foreword to my upcoming book, Addicted To Noise: The Music Writings of Michael Goldberg (Backbeat Books). I’ve read nearly all of Marcus’ books, and Folk Music is brilliant. He told me he thinks it’s his best, and I agree with him.

I met with Marcus on September 16, 2022, at his home on a quiet, tree-shaded street in Oakland, not far from the borderline that separates Oakland from Berkeley. We talked for an hour and a half in his basement office, which, as might be expected, contains shelves of CDs, DVDs, Records and books. A hardbound copy of Folk Music, which was not yet available at the time of our conversation, was close at hand. He was wearing a black sweater, jeans and his round tortoise shell glasses.

Michael Goldberg: You’ve previously written three books about Bob Dylan. Why did you want to write a fourth book about him?

Greil Marcus: Well, I didn’t. I thought the idea of me writing another book about Bob Dylan was ridiculous and pointless. You can only write so many books about one figure before becoming sort of a self-parody. That was my attitude a few years ago. And then I was approached by the person who runs the Yale Jewish Lives series. And that’s a series that’s been going on for quite a number of years and it’s been really successful. They find an author to write about some significant Jewish figure and write a short biography that is new and different and called for because the writer has an original perspective. That’s the concept. So, they’ll do Albert Einstein. David Ben-Gurion. These very eminent figures. And then they start going further afield. Maybe Sarah Bernhardt. All kinds of people and it really opens up. And so, I was asked to do a book on Dylan as a Jewish life. And these books have sold well, they’ve been reviewed well, there are people who follow the series and buy them all. So, it really has a following.

So, I sat down with the person who approached me and I said, “I don’t really see the point of this.” There have been dozens of Bob Dylan biographies. Some are good, most of them are terrible, most of the people who write them can’t write, some people do remarkable original research, some people cobble together what other people have said but all in all what it comes down to are there are certain stations of the cross that you have to account for. These various turning points in his career. And it’s been—there is a narrative, there is a fixed story already that any biography would have to address and what’s the point. It’s been done; it’s been done to death. So, I said, “No, I’m not the right person, I don’t even think it’s a good idea.”

But then I thought about it a little bit, and I thought, what if you organized it around a limited number of songs without any notion of what those songs would be. And you’d ask questions like, What sort of person would it be who could write these songs? And what do these songs tell you about the kind of person needed to write them? So, you focus it all on the songs. You get to the question of who this person is and where he’s been and what he’s done without addressing that directly. You don’t go into private life. My talisman for this book was something he said in a short interview in USA Today, where he said, “Look, I’ve been married a bunch of times. I’ve never tried to hide that”—which isn’t really true but he’s talking, I’m not talking. He said, “I just don’t advertise my life,” which struck me as a very eloquent and lovely thing to say. “I don’t advertise my life.” He said, “I write songs, I make records, I play on stage, that’s it. The rest is nobody’s business.”

And I said, “Yeah, the rest is nobody’s business, certainly not my business.” It’s not something I’m interested in. I don’t care about Bob Dylan’s inner life. The only way you’re going to capture Bob Dylan’s inner life is in a novel like Don DeLillo wrote with Greater Jones Street. I’m not a novelist. That’s not my purview, that’s not my territory. So, I said, “This is a person who writes songs, who makes records, who plays on stage—those will be the parameters of the biography I’m going to write.” And when I focus on a given song, say it’s “Ain’t Talkin’” from 2006, I’m going to look at many, many live performances of that song to see how it changes, how it grows, how maybe he loses interest in it, how it begins to fade. Whatever it turns out to be. I’ll follow the performances and I’ll try to tell the story that they tell. And that will be a story of both the person who created the song, who is singing it, but also the song as a thing in itself, that makes certain demands, that asks to be sung more quietly or more loudly, whatever it might be in a given moment.

So, I went back to the guy and I said, “What if I approach it this way?” And he let it slip that they had already commissioned a Dylan biography and it had been delivered and they rejected it. That’s a fairly unprofessional thing to do, to let that go. I was kind of taken aback by that. I said, “You got a book and you turned it down?” That’s very unusual for a publisher. They might say, “We have problems here. We’d like you to go back and look at that.” But it’s unusual for an author who has some reputation, which I assumed the person they had in mind had, to just be rejected. Then he let it slip who the person was. I later found out, looking at an earlier Jewish Lives book of Hank Greenberg the baseball player, that they had listed “Coming Soon: Bob Dylan by Ron Rosenbaum. Ron Rosenbaum’s a very eminent journalist who has interviewed Dylan a number of times, did a Playboy interview with him in 1978, so that’s a very comprehensive interview and I thought, “You’ve got a book from Ron Rosenbaum, who I know very slightly, who’s a great journalist. How bad could it be?” Anyway, he liked my idea. He took it to the editorial board, but they were feeling so burned by whatever the problem had been that they didn’t want to take a chance on odd.”

So, in December 2019 I was meeting with my publisher at Yale to talk about a book that I had coming out and he said, “What’s next, what are you going to do, what do you want to do?” I said, “There isn’t anything really.” But I told him this story that I just told you and I added more. I mean I had written up a précis for the book—two, three pages—but it included the story of my grandparents and the 1933 San Jose lynching which he found just riveting. He said, “Whatever the Jewish Lives series does with Yale has nothing to do with what I do. I want to publish this book. I’ll just do it with Yale.” I said, “OK,” ’cause by then I didn’t want to give it up. I had an idea; I wanted to pursue it.

So, that’s how the book came about. It wasn’t that difficult to write. I did it kind of slowly for me and I knew when I finished it, it was good. It basically had no editing—I mean the copy edit took months and it was every single sentence scrutinized. The Yale copy editor I worked with is a real editor. I mean he fact-checks everything, he questions sentences, he makes fun of you, he writes emails where he’s basically throwing up his hands and saying, “You’ve got to be kidding me.” It’s a very contentious, wonderful process. And I knew, for what it’s worth, this is the best I can do now. I think it’s my best book. And it’s good to feel that way about a new book. But I know that I can’t write better than I did in this book. And I was surprised that at this age I could still do that.

Goldberg: It’s interesting that you came 180 degrees around. You went from, there’s no point, to where you had this idea that there was something new that could be done.

Marcus: Well, yeah. I managed to think of a way to tell the story without talking about “Dylan goes electric at Newport,” “Dylan becomes a born-again Christian”—I mean those things are mentioned in stray sentences, they’re not examined. I didn’t feel the responsibility to explain his life. And that’s why the book begins with a two-page chapter called “Biography,” where I simply run down the arc of his life up to this point and I felt in two pages you could really do that. You could say, here is a person who was born at a certain time, he did certain things, this is why we’re interested, that’s that.

Goldberg: What’s so special about Bob Dylan?

Marcus: Well, I’ve always said, I’ve always believed, that it’s the voice, it’s the inflection, it’s the way of dramatizing small things, enormous things: small things expand in the way he sings about them, enormous things like the meaning of life or the nature of freedom are brought down to earth in the way that he sings about those things. It goes back to the first time I ever saw him. In 1963 at a Joan Baez show in New Jersey, an open-air rotating stage show where she brings out this guy whose name I didn’t even catch and he sings two or three songs, one of which is “With God On Our Side” and I’m just absolutely stunned. He sings that song once and it’s like I’ve memorized the entire song, or rather, the entire song simply lodges itself in my memory, I didn’t make any effort to memorize it, it’s just there. It has come across that directly and that powerfully because of the modesty and restraint and regret and cynicism he’s able to convey as he sings this song. It’s not a text, it’s not a statement, it’s an event, it’s an act. And anybody else could have sung that same song and have no effect at all. It is a set of propositions, it is an argument, so anybody can make that argument, but not anybody can make that argument come to life and make you feel like you’ve already lived out that song because you went to a public school and learned public school history, which is what that song is about. This is what we learn in school about the modern world.

So that’s what’s so special. Yeah, he writes songs that nobody else could write. He did that in the early sixties, he’s still doing it today. There’s no question about that. He has a purchase on the world. He’s able to play with the world – with its fears, with its desires, with terror and fulfillment and gratification. All those things come into play. But were Bob Dylan to die tomorrow and make no more records and sing no more songs, his legacy would continue and people would continue to sing his songs and record them but they would lose one, two, three dimensions. They would be tributes, they would be footnotes, they would not be capable of bringing something new into the world, which is what he does.

I mean I said I was surprised that at my age I could write as well as I think I have in this book. But Bob Dylan, in 2020, when he was 79, puts out “Murder Most Foul,” which is not like anything anyone has ever heard from him before in any way, and it becomes—and who knows how Billboard calculates these things these days because it was never released as an object until it became part of the Rough and Rowdy Ways album, but it wasn’t released as a single—but it became the number one single in the country, simply by the number of hits it got on his website and then all the other places where it immediately popped up. Anyway, you can tell I’m very loquacious so stop me if you want to ’cause I can go on forever about anything.

Goldberg: Early on in the book you write that because “in the songs he sings Dylan can make anyone’s life his own, it calls the whole notion of biography or even biographical significance into question.” Can you elaborate?

Marcus: Yeah. Let’s put it this way. Mick LaSalle, who I think is a truly great critic, and he is the most incisive critic I know, he can say so much, he can make a complex argument in a very few sentences. And so, he’s talking about the Johnny Cash bio-flick of a number of years ago [Walk the Line] where Joaquin Phoenix plays Johnny Cash. It really is a tremendous performance, a real inhabiting. You get the feeling about two-thirds of the way through that Joaquin Phoenix feels like he really is Johnny Cash. I don’t mean that we think he is; he thinks he is.

And Mick LaSalle says, the problem with the movie just has to do with the limits of the biographical film. There are real severe limits there. They boil things down to a simple notion of causation. I’m saying this in much more words than Mick did. He says, Are Ray Charles and Johnny Cash both great artists because their brother died? Is that what really warped them and impelled them to live a larger life than most people do. And he said, Yeah, sure, that makes sense. And then he says, But of course not. That has nothing to do with it. You don’t find causation. It doesn’t work that way. So, you aren’t going to find causation if you are alive to the rhythms of life. You cannot say that this incident in Bob Dylan’s life, this trauma, this decision, this break, whatever it might be, is the reason he was able to write with such stark and shocking imagery in “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”— “I saw ladders covered with water…” Ladders covered with water? What does that mean? I mean it doesn’t mean anything, but it’s a fearsome image and that’s what it’s meant to be. And is it because Bob Dylan only had one younger brother instead of sisters and brothers all over the place that he wrote that song? Of course not. It has nothing to do with that. And has nothing to do with his inner life. It has nothing to do with him lying awake at night reliving some mean thing his father once said to him and suddenly these verses came out. It could have happened that way. Who knows? Who cares? You know?

The creative act is a mystery even to the person to whom it happens. I mean Dylan once said, he’s talking to Robert Hilburn about writing “Like a Rolling Stone,” and he said, “It’s like a ghost came and gave me that song. I didn’t write it. It was just given to me.” Well, any person who’s ever been involved in creative activity knows that feeling. That’s simply part of the creative process where things—if you’re a singer, if you’re a painter, if you’re a writer—things appear on the canvas, something comes out of your mouth, something appears on the page and you think, “Where did that come from?” I didn’t conceptualize that. I didn’t work that sentence out. I didn’t even think of it. It just showed up. Who wrote that? I didn’t write that. Everybody knows that feeling. So, you weren’t going to find a source for that other than the creative process itself.

I mean Dylan himself has often said, “You have to put yourself in a semi-conscious mode, you have to put yourself almost in a trance state so you can receive these external messages that tell you what you’re doing and how you should do it. You have to put yourself in a state of being open and receptive.”

In order to write this book, I read one biography, which is my favorite Dylan biography, which I’ve read before by Howard Sounes called Down the Highway. I think it’s the most interesting and original and unburdened of the biographies that I’ve seen and might be the only one I’ve read all the way through other than Anthony Scaduto’s Dylan that came out in 1972. And then I read every book I could find collecting interviews with Dylan. And I read them through, and I made notes, but I pretty much absorbed pretty much everything Bob Dylan said about anything. So, I had this reserve of his own understanding of his own work at hand. And along with listening, that’s really all I needed.

Goldberg: This is a really interesting thing you wrote. “The engine of his songs is empathy: the desire and ability to enter other lives, even to restage and re-enact the dynamic others have played out, in search of different endings.” Was that just obvious to you? Have you always felt that way about the songs he writes and sings?

Marcus: I had felt that way, but I didn’t conceptualize it until I read him say, “I can see myself in others.” He said that at a press conference in Rome in 2002. So that’s a long ways into his life and into his career. But even when he was first in Greenwich Village and he’s hanging around the Folk Center that Izzy Young has and he’s getting his mail there and he’s trying out instruments and looking up old sheet music, you know, learning, ’cause it’s like a library, it is a center of knowledge. And everybody else is coming by and they’re swapping songs and whatever they do. And he talks to Izzy Young, who makes notes on this. He says, “You know I just had this great idea. I’m going to write a song about Emmett Till.” Now that’s interesting. Emmett Till was lynched in 1955 and here it is, 1961, and people are still very focused on Emmett Till as an event that’s happening in the moment even though it’s six years in the past. He says, “I’m going to write a song about Emmett Till in the first person and I’m going to pretend I am him.”

In other words, he’s going to sing, he’s going to be Emmett Till down in Money, Mississippi, he’s going to be Emmett Till while he’s being beaten to death, he’s going to be Emmett Till after he’s dead and still thinking about what happened to him and what is this about. You can begin to imagine what an interesting song maybe that might be, which he never did write. He wrote a song about Emmett Till, about a terrible thing that happened down in Mississippi, but it was a straight third person narrative. What an interesting idea. And then he says I’m writing a song about the death of Robert Johnson, this is after he first hears Robert Johnson in 1961, he’s never heard of him before, most people hadn’t at that point. And I thought, maybe he’s going to write a first-person song about Robert Johnson too. What an interesting idea. That’s what he finally ends up doing with “Murder Most Foul,” where he’s singing out of the mind of JFK, after he’s been shot for the first time. After he’s taken the first bullet but isn’t dead yet. And he’s thinking, “What’s going on? What’s happening? Do you know who I am?” It’s just incredible that it takes him all those years to fulfill that fantasy of a song, from Emmett Till to JFK, from the least powerful person in the United States to the most powerful person in the United States and both of them subject to being killed at any moment at any time. Just amazing.

So, I always thought—I never heard “Like a Rolling Stone” as this spiteful putdown of some obnoxious rich girl who needed to be put in her place. Now I know lots of people have heard this as just that. I never heard it that way. It just never communicated to me that way. It was always somebody saying, “You’re in trouble. You need help. You don’t understand what’s going on. Other people might have a better idea of what’s going to happen to you and if you listen to them, you might be better off.” It’s not about any specific person, it’s just about anybody who suddenly finds themselves with the ground beneath their feet [that] has disappeared and they’re floundering and there’s no connection that can be made and everything that you ever relied on has betrayed you, what are you going to do? How does it feel? It feels terrifying and by the end of the song it feels absolutely liberating. That’s what the song is about to me. So, it is a song about empathy. Dylan himself said, “I was trying to save somebody from drowning.” And, well, OK, even if he didn’t say that you can hear that.

But, like I said, I read through all these interviews. Hundreds of different kinds of interviews and I followed Dylan’s cues. In a way I let him tell the story. Not just quoting from [Dylan’s memoir] Chronicles, which I tried to do as little as possible, but it was difficult because the book is so alive, so ridden, it is just as rich in its imagery as his songs. That party at the beginning of the book. The grand Greenwich Village party that he walks the reader into. There’s so and so and here’s this person and here’s that person and I remember reading it, this is too good to be true. This is 20 different parties over three years and they’re parties Dylan went to and parties that he heard about and he’s all putting them into this one fantastic set piece. I don’t know if that’s true. Maybe it was one party but that’s how it came across to me and it was more wonderful to me that it was in a sense fiction than if it had simply been a report on this great party I got to go to. Who knows?

Goldberg: What do you hope people will get from reading the book?

Marcus: I hope they have fun reading it. I don’t have ambitions for my books. I don’t want them to teach people anything. I don’t want people to come away feeling different about themselves. I think life is interesting and it’s the writer’s job to make it more interesting than it might otherwise appear to be. And if people have fun reading it, if they find it interesting, then they will find other things in their life more interesting. Not necessarily a Bob Dylan song.

One of the truest things about influence, about the effect that a creative work has on another person was said by Bob Rosenthal, who was Allen Ginsberg’s secretary for 20 years. There was a book [The Poem That Changed America: ‘Howl’ Fifty Years Later] that came out a number of years ago, and it brought together god knows how many writers to write about “Howl,” the Ginsberg poem, and just about every single thing in that book begins with, “The first time I read ‘Howl’ I realized I had to be a poet or I had to be a novelist, I had to be this creative person, I had to give voice to what was in me and give it to the world”, and it was just unbearable, the pompousness and the pretentiousness of this and at the very end, Bob Rosenthal addresses this. He says, “People are always saying, ‘Oh, I read “Howl” and I was supposed to go to law school, or I was supposed to go into my father’s plumbing business and I realized no, I’m a poet. I have things to say. And so, I became a poet’.” And he said, “If the poem is liberating, that really is a very narrow view of what it might do. Maybe it’s that poem that made you become a lawyer or, for that matter, a good plumber. I mean, maybe people thought you were worthless, you were never going to amount to anything, you were just a lump of clay that no one ever bothered to mold into anything. And you read that poem and you said, ‘No, I’m going to go out and live in the world. And the way I’m going to do that is I’m going to go to law school. And I’m going to learn now the world works and I’m going to see what I can do to become part of that.’ That’s a great ambition. So, instead of turning someone from the conformist, soulless life of becoming a lawyer as opposed to a poet, maybe this poem helps you become a lawyer.”

And I thought, that is so great, that is really wonderful. That is really an open spirit and it speaks for the narrow, the small souls that so many so-called poets carry around inside themselves. That is an expansive vision of life. That is not a shrunken vision of life. And so, you know, if people read an interesting book it will spark their interest in other things. Not necessarily having anything to do with what the book is about. I hope people read the book and get to the end and they say, “That was something. I’ve been somewhere reading this book. Now I can put it aside and maybe the day is 10% bigger than it would have been before.”

Goldberg: What is the job of the critic and what value do critics bring to the work they are writing about?

Marcus: Well, they’re able to dive into stuff that people care about without necessarily even knowing that they care about [it]. Whether it’s a political speech, whether it’s a historical event taking place in our present, whether it’s a book or a movie or a song, a creative act in the world, and dive as deeply into that as they can. And say, This is what’s happening here, this is what might be happening here. The whole world can be found in this song, in this painting. You’re never going to get to the bottom of it but you can swim in it, you can make it define your world for a moment. And the reason other people don’t necessarily approach these things that way is because they’re busy. They’re doing other things. They have other kinds of jobs. They have other demands on their time. Whereas the critic, that is his or her job. That’s what they’re supposed to be doing. So, they can devote all their time to it and go as far as they can.

You have critical events in your life, anybody does. The last time I was in Venice [Italy] I went to the Peggy Guggenheim Museum, as I had done any number of times before. I stood in front of the Jackson Pollock painting “Alchemy” from 1947. I’d seen it before, but I’d never really looked at it. So, I walked up to this painting, which is as dense a Pollock painting as there exists on earth, and I walked up to it and I was drawn in by its gravity, by the weight of detail of paint on the canvas. And it began to seem, as random or as thrown as the paint might have been—here’s the yellow and here’s the red and slop here and slop there and all of my fingers, however it was made—everything in the painting began to seem intentional, began to seem composed or made. So, I said to myself, OK, I’m just going to look at one square inch of this painting—and it’s a big painting—and see what I see.

So, I spent about half an hour looking at a square inch, and I realized it would take me my entire life, or maybe longer than I have, to see the whole painting, to look at the whole painting. That not just the world, the universe was in this painting and the universe is unlimited. There’s no way you’re ever going to map the universe and find out everything that’s in it. It’s not going to happen and that’s because of human limitations and also because the universe is constantly creating new stars and new planets and you can’t keep up with it, and it’s racing away from itself, you’re never going to catch up with the universe unless it implodes and goes back to the one tiny bit of carbon that it started out as before the big bang. That’s what a critic does. A critic can say, I’m going to devote the next year of my life to looking at this painting or listening to this song and I’m going to see how far I can go with it. Other people have other things to do with their lives but they might find it interesting to follow someone else doing what they don’t have time to do in regards to something that has touched them too.

Goldberg: Well, you do that. You’ve been doing that for quite a while. You certainly have been doing that since you started writing about certain songs and going really deep into them and you did that back in your Basement Tapes book. But my impression is most critics don’t do that.

Marcus: Some people do, some people don’t. I don’t know why other people do what they do, why they don’t go farther or how they go so far. Again, going back to Mick LaSalle, he wrote a paragraph about Brokeback Mountain, and in that paragraph, and it wasn’t a long paragraph, was an explication of the ethos of what it means to be an American. That if you can’t say who you are then you’re not free and you’re supposed to be free in America, you’re supposed to have the right to say whatever you want to say and if you can’t do that, somehow you’re not an American. Is that your fault? Is that because someone has prohibited you from living a full life? Well, you have to think about those things. So, I think Mick has the ability to go absolutely down to the bottom and not necessarily have to write a whole book about it. I don’t know why other people what they do. I know that some critics, like Tony Scott in the New York Times, can occasionally come up with a sentence or two sentences that illuminate a film and take it into the larger world. Just in a weekly review of something. He can leap out in a very few words, he can connect the occasion of somebody making a movie and releasing it and maybe you’re going to go see it, into something much more expansive and liberating and invigorating.

Goldberg: You started writing about music but you were talking about many other things in the context of writing about music, particularly politics. Did you make a decision to become a critic?

Marcus: Well, no. I had written college papers about music and politics, music and America, music and the greater world. I started doing that when I was maybe a junior in college, probably in 1965. And then in 1967, late 1967, I noticed a bundle of newspapers outside Whelan’s Smoke Shop across from the Berkeley campus on Bancroft and I looked at it, something called Rolling Stone, and I pulled one up and I started looking through the pages and I could tell, just by looking at the design and what the stories were about, this was Jann Wenner, who I had met years before when we were both freshman at Cal. And I followed his career writing in the Daily Cal as Mr. Jones and writing in Ramparts and Sunday Ramparts, record reviews he had written and sort of polemical pieces he had written, I just knew this was Jann, it has his fingerprints on it.

And about a year later I went into Record City, which was a little record store on Telegraph just steps off of Bancroft, a little cavern of a place but full of stuff, and in the window they had an album called Magic Bus: The Who on Tour. And I thought, Oh my god, a Who live album, how great. This is what anybody who cared about the Who had been waiting for, for years. It was 1968. We first saw them the year before, but I’d been listening to their records since well before that. Oh fantastic, a Who live album! I go in, I buy it, I take it home I play it, it’s not a live album, it’s just a bunch of B-sides from singles and stuff they hadn’t bothered to release on albums because it wasn’t good enough. It’s just a bunch of throwaways and I felt ripped off and cheated and I began to think of all the random Who tracks that were out there like the 45 they put out when Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were jailed for drug possession and they [The Who] wanted to keep their work before the public so they re-recorded Rolling Stones songs. All kinds of stuff.

So, I put together—if they’re going to put together an album of random this and that, they could have done a whole lot better and here’s what they should have done. And I wrote it up as a record review and I sent it into Rolling Stone and two weeks later I pick up the next issue and it’s there and a week after that I get a check for actual money, for $12.50, and I think, this is easy, this is fun, I should do this more often. And then I get attacked in the San Francisco Express Times as a naïve amateur who doesn’t understand the vagaries of record production and what a record company needs to do to keep an act before the public and they have to rush out product. This is by Paul Williams, the editor of Crawdaddy, the most eminent rock critic in the world, attacking me for the first piece I’ve ever published anywhere. That felt kind of weird.

But I realized, also, I wrote something and people read it. So, I started doing that and I became an editor at Rolling Stone and then I became part of the four-person editorial board that ran the magazine, for six months, until I got fired in 1970; and I was in graduate school all the time. I was planning to become a professor. And then in 1971 I was given the chance to teach the American Studies honors seminar for sophomores, a class I had taken in 1964, ’65 I guess, and it was the class that really did change my life, that really did open me up to the world I wanted to live in and investigate and write about always and I had great teachers: I had Mike Rogin and Larzer Ziff, Mike from Political Science, Larzer Ziff from English. This honors seminar was a bond between the students and the professors, it was all taking place during the Free Speech Movement, where everything you read and talked about was heightened, [and] had an immediate relevance to your life.

So, I’m given the chance to teach this as a graduate student. They’ve never had a graduate student teach it before; it’s always been professors. I’m just thrilled, I’m honored, I’ve been knighted, I’m so proud of myself and I taught that seminar for a year and I was God awful, I was terrible, I was an awful teacher. I had no patience. A teacher without patience is not a teacher. And I realized that I could not do what I’d always thought I was going to do, I’m not going to become a professor, I can’t devote my life to doing something I’m not good at, that I’d be faking. So, I dropped out of graduate school, I didn’t get my PhD and at that point the only other thing I knew how to do with my life was write. So, I wrote Mystery Train.

Goldberg: What’s been the most challenging thing for you about being a writer and a critic?

Marcus: Do you mean in general, in specific?

Goldberg: If this doesn’t make sense as a question we can do something else… In looking back now, were there things that were challenging where you had to really look at what you were doing in a certain way or something you were doing was really hard?

Marcus: No, it hasn’t been hard. When you’re writing and you’re just fixed on something, you can sit there for five or six hours and write constantly because you’re so interested in what you’re doing and what might come next and what might turn up as you write. You want to find out what that is. Some books have taken a long time. Lipstick Traces took nine years. The research only took about three, but after three years I had basically everything I was going to need to write that book, and understanding how to write it, how to tell the story. There were a lot of sort of failed experiments but finally I figured it out. And at one point I got stuck but I got stuck because I was so fascinated, because the story was so big, that’s how it appeared to me, and I had to find some way to bring it down into human scale so that I could make it a story that would both make sense and be interesting. Learn what to leave out and how to do damage to the material, not be in awe of things people had done, but to look with something of a cynical or critical eye. Not let the people who I was writing about write the book. It’s what I think; it’s not what they think.

That was difficult. It took me a long time. Here I am writing a book about the European avant-garde going back into the Middle Ages where a self-selected elite, the avant-garde, says, “We see the future, we understand what this is all about, nobody else does, and we have to put this knowledge into the world either surreptitiously or in the most loud and spectacular way possible, but we have to get the word out. We’re operating behind enemy lines but this is a matter of life and death, but we know the truth and the truth will save the world and it’s up to us to do that.” That was the ethos of the European avant-garde. There is nothing less American than that perspective on the world.

America is built on—whatever the realities may be—the valorization of every individual, the right and the burden and the obligation of every person to say what they think, to affirm what they believe, to recognize the essential equality of all of us in any given community, whatever our level of education, whatever our background, however we appear to be. You have to recognize the humanity of every other person and you cannot presume that you’re better than anybody else or that anyone is better than you are. That’s the American ethos. That is an absolute contradiction of the European avant-garde ethos and here I am, Reagan has become president, and I’m fleeing to Europe, I’m fleeing hundreds of years into the past of Europe to live in a different world because I’m turning my back on America and America has turned its back on me by electing Reagan as president. That’s how I felt.

That was the journey I was on. And it was sometimes painful and sometimes, often, confusing and I didn’t know what I was doing but it’s where I wanted to be. Now you can call that a challenge or you can say what a fucking paradise for a writer to be able to live in this other world and investigate it and even make sense of it and make it into a story that other people might find appealing and even life changing in some small way, opening them up to possibilities in their own life that they didn’t know were there. So, I don’t really think of that as a challenge. I think of that as a privilege.

Goldberg: Getting back to Bob Dylan, In the book you quote Suze Rotolo: “Much time was spent in front of the mirror trying on one wrinkled article of clothing after another, until it all came together to look as if Bob had just gotten up and thrown something on. Image meant everything. Folk music was taking hold of a generation and it was important to get it right, including the look—be authentic, be cool, and have something to say.” Why did you include that in the book? What do you think that says about Dylan?

Marcus: I think it says that he was thinking through everything he did all the time. Towards some greater goal. Which essentially, in Dylan’s case, meant not just being bigger than Elvis but also bigger than Thomas Jefferson, let’s say. People don’t have great careers without ambition, without fantasies. There’s a way in which the truest pop song there is, is, “Everybody Wants to Rule the World.” To acknowledge that. “Yeah, I want to rule the world. Maybe I’m not the right person, maybe I just want to damn the world, maybe that will do. Maybe I just want to celebrate the world. Now that’s pretty sappy. I think I want to speak for the world. People have great ambitions. Elvis did. Bob Dylan did.

One of the great things that Elvis did was he showed people how big, big could be. Nobody had any idea before Elvis. The way in which teenagers screamed for Frank Sinatra as they screamed for Elvis. Sure, that had happened before. They screamed for Rudy Vallée. For that matter, they screamed for Al Jolson. But they didn’t divide the world in half, for and against. This is the end of civilization; this is the beginning of civilization. That’s what Elvis did. He divided the world in half. You had to take a side. You had to make a stand. You had to have an opinion. That was not true with Frank Sinatra. Or Rudy Vallée. That’s how big, big could be. And that’s the much-expanded arena where Bob Dylan was able to do his work.

And so yeah, if you’re going to come across as somebody who just got out of bed and was suddenly impelled to sing a song, to tell people how the world looked to you, you couldn’t look as if you’d spent weeks and weeks and weeks figuring out how to do that. It just had to come out. And Dylan’s very clear. He writes in Chronicles about going to the New York Public Library and reading newspapers on microfilm from the time of the Civil War. First, he wants to go read about this battle, then he starts to read all the advertisements and the advice to the lovelorn columns or whatever else is in the newspaper and getting a sense of this is a whole world, this is what was happening. The Civil War was being fought out on this battlefield and in this household but over here in this town it’s not even happening. Or in the pages of ‘how do I cure my grippe’ it’s not even happening.

And so, he gets a sense of how these enormous historical events can upend the lives of millions of people and at the same time not touch those of others. How strange. How weird. And it makes him realize that he could sing a song about the end of the world, and maybe its redemption, like “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” and somehow find a way to tell people that everything is in jeopardy, that everything is up for grabs, that which way history will go has not been determined and partly it’s up to you and how you will understand your place in the world and what you might do about it.

And in order to put that across in a given milieu, the milieu of folk music in New York City, you have to look a certain way, you have to have a certain attitude, you got to have a certain authenticity which is completely made up and constructed, in order to make your case. You’ve got to look the part in order to get people to listen to you and take you seriously. That’s what she’s saying. That was a complex statement of hers.

Goldberg: You quote John Hiatt who says he was 13 years old, in the car with the radio on and his mom went into a drug store and then “Like a Rolling Stone” came on the radio. “I was certain when she came back out she wouldn’t recognize me. I felt like the song had changed me that much, just by hearing it.” Did you have that kind of experience when you first heard Dylan?

Marcus: I never had that particular thought, but there was a time when I was 20 and “Like a Rolling Stone” came out, maybe over the next year, over the next two years, and I found myself listening to that song over and over again and I found ways to listen to it on headphones where I could tune out certain instruments and only listen to the piano or only listen to the guitar playing. I mean I could cognitively do that and hear the song in its parts, and it became endless and bottomless. I never got tired of listening to it, I never have. It always carries with it a sense of event, of contingency, not of a finished product, not of a text, not of something that has been perfected, but of something that is happening as you listen, which means that it might not have happened. And all through that song you can hear that sense of contingency, that people are finding their way through the song in the dark. They don’t know where they’re going; they don’t know what’s going to happen when they get there or even if they ever are. That’s how it felt to me, that’s how the song felt to me.

And it was a shock when I finally got to listen to the whole recording session to find out that that was true. That by the time they get into the third verse when they’re recording the song in the studio and they’ve done god knows how many takes before and they’ve never gotten past the second verse. It breaks down, somebody makes a mistake, Dylan flubs a line, it just doesn’t feel right.

Sometimes they don’t make it through the first verse, sometimes they make it all the way to the second verse and this is the first time that they get past the second verse and Dylan is singing and they’re following, they’re trying to play with him, but in their rehearsals they’ve never gotten to the third verse. They don’t know what’s happening in the third verse and Dylan is singing and then they get to the fourth verse, and they don’t know if there’s a fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth verse. There could be. Maybe they were going to go all day. Who knows? But there are only four verses and Dylan leads them out and they follow him out of the song and then they go back to trying to record it again and stopping again with the first verse. One more time making it all the way through but by then it’s a complete mess.

And it just so happened that there was one take in this two-day recording session where the song had a body. This is the only take. And that means that they could have gone through these whole two days and never gotten to the third verse and finally said, you know, maybe we’ll go back to this sometime, but it’s just not happening. And so that song wouldn’t exist. That sense of accident, that sense of grabbing onto the accident and saying, “No, this isn’t an accident, this is the way it was supposed to be, we just didn’t know that.” That is what I do as a critic. I look for those kinds of moments where something is happening that didn’t necessarily have to happen. It’s interesting, there’s a version of “Ain’t Talkin’” that isn’t nearly as good as the one that was released where all these lines from [the Roman poet] Ovid that Dylan weaves into his song aren’t there. They’re not there yet. And he realizes that something’s missing. Some spark, some sense of timelessness, the world’s end. “If I find my enemies ever sleeping, I’ll just slaughter them where they lie.” The song needs that. It needs a sense that more is at stake. Somebody is walking through the world and part of him doesn’t care if the world ends under his feet and part of him wants justice, wants revenge, and part of him is standing outside this drama and simply watching himself and other people move through it, as if everything is fated, as if nothing could affect the ultimate outcome. And you watch that with a sense of cynicism and despair, but also maybe a sense that this is what life is. It is beyond our control. And so, the song is rumination over that.

I knew when I first heard that song, I just knew, the song came to me, as a critic, as a writer, I’m never going to get to the bottom of this song and this song is always going to be mocking me saying you don’t know, you can’t hear, you don’t understand and you know how much is here and you’re seduced by this song but you’re never going to get it, not really. And so, for years I wrote around it and I circled it and I wanted to do that and with this book I thought, well I’m just going to give it everything I’ve got. Not to solve the mystery of the song or to decode its puzzle or anything like that, because it is a lived experience. I wanted to see how deeply and broadly I could live in this song, as if it were the world. So that’s play, that’s fun. That’s not a challenge. It is a challenge, but once I gave up on the idea that I could ever meet it, then I’m just having fun.

Goldberg: You wrote about “Blowin’ in the Wind,” that it was the song you liked least on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, you thought it was obvious and then, later, a point came where you had a very different take on the song and you spend 80 pages or so talking about that. You express your opinions very strongly over the years. You once wrote that the Beatles singing “Money,” a song they didn’t write, was the best thing they’d done of their early recordings. Obviously, a lot of people would have a different opinion. Do you ever feel like, “Maybe I’m wrong about this song that I have this opinion about.” To make a statement like that—this is the best song the Beatles did at this point in time—

Marcus: Sure. Everybody can be wrong. But what does that mean to be wrong. What you should really wish for is the ability to be open to hearing or seeing or understanding something in a way that you didn’t before, rather than to hold onto your own opinion as if to change it or have it changed for you somehow brings your integrity into question. No, I didn’t like “Blowin’ in the Wind.” I thought it was pious. I thought it was condescending. I thought it was boring. I thought it was everything you didn’t want a song to be when I was 20, when I was 18, when I was 30, when I was 40, whatever it was. And I didn’t ever think about it as something that was interesting. And then I was asked to write an afterword to an illustrated book of “Blowin’ in the Wind.” The lyrics on the page and somebody doing pictures to illustrate the lyrics. It’s a kids’ book. It’s a little kid’s book. And so, I’m asked to do this and I agree to do it because the pay was really good and I could use the money so that’s why I did it. So, then I thought, “What am I going to write about this?” And I began to think, “Ok, this is a book for six-year-olds. If I were six years old and I was hearing this song, what might I think? What might it say to me?” And hearing it and trying to listen to it that way opened the song up for me and completely changed it. And made it come across in any given performance—by Dylan, by other people, by Dylan over the years, over many, many, many years—it just became an endless universe.

There was so much to say, so much to write about, so much to hear. And I don’t think it was because I was wrong before. I don’t know that I was wrong before. That was my honest reaction to that particular happenstance in the world. But then I was able to hear it differently, and to hear it differently from the beginning to the end. And hear why the song is so rich for Dylan. He is able to continue to sing it in radically different ways and have it become, not a reference to the past. If he sings it on this Election Day or that Election Day. It’s interesting how often he sings that song when he’s performing a concert on the day of an election. It’s like an election sermon in the Puritan sense, when Puritan preachers would give a sermon about the nature of the community on the day that electors to govern the community were selected. What are we really choosing? What burden is upon us? What will be the consequences of our right choice and our wrong choice? What is our true mission? Who is going to fulfill this mission, who is going to fall short?

It is performed and presented that way. I was there. I was in Northrop Auditorium at the University of Minnesota in 2008 and it’s on everybody’s mind, that’s all anybody is thinking about as they’re sitting listening to Dylan play and he ends by saying, “I was born in a word of darkness in 1941 and I grew up under the atomic bomb and I’ve lived my entire life in darkness but I think things are going to change now.” Using Obama’s campaign slogan. And he timed the concert. This was done very intentionally. He timed the concert so it would end five minutes before ten o’clock. And it was ten o’clock when the networks were going to be able to call the election because the polls had closed all over.

And we file out of the auditorium and we’re in the anteroom of Northrop Auditorium where there’s this giant TV screen that has been set up. And everybody’s there. Thousands of people from Northrop are jammed into this anteroom staring at this TV screen. He had ended the show so the audience would have time to file out and see the election called. It was all set up that way. He wasn’t going to stop a half an hour early; he wasn’t going to go five minutes too long. So that event became part of the concert and vice versa. And I did something—I was so shocked. I was standing next to one of my students ’cause I was teaching at the University of Minnesota at that time and she happened to be there too and I was standing next to her and when they called the election for Obama, I hugged her. And then I thought, “I’m a teacher, I’m hugging a student. I can’t do that. This is terrible.” And I said, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry. I got carried away. You could have been anybody.” She said, “I know, I know.” I’m the kind of teacher who never sees a student without the door open. I couldn’t be more scrupulous about that and I thought, “Oh, this is so terrible.” But it was just an impulse of joy.

Goldberg: You were so moved.

Marcus: Yeah, sure.

Goldberg: You quote Mavis Staples: “How could he write ‘How many roads must a man walk down before you can call him a man?’ That is what my father went through. He was the one who wasn’t called a man. So how, where is he coming from? White people don’t have hard times—that was my thinking back then because I was a kid, too. What he was writing was inspirational… It’s the same as gospel. He was writing truth.” And what she said is kind of in that film with Malcolm X and Sam Cooke—fictionalized. She seemed to think that was an amazing thing that he could write that. That he could think to write that.

Marcus: Well, that’s what the book is about. The book is about his ability, his instinct, his need to see himself in others. To live out other people’s lives in his imagination. And to write a song like “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which is about racial injustice and everybody knew it was about racial injustice, you didn’t need to have anybody explain to you that this was a song about, from, to the Civil Rights Movement, when nothing of the sort is mentioned in the song except “How many roads must a man walk down before you can call him a man” maybe. Except Bob Dylan says, “No, that just came from ‘John Henry’”— “Man ain’t nothin’ but a man.” We’re all the same; we’re all equal in our personhood, to the degree that it flowers, to the degree that it withers. The song has no specific reference in it at all. Can be about anything; can be about nothing. Except no one has ever misunderstood it. No one ever didn’t get what the song was about. And yet it’s bigger than that, it’s more open than that. Which is why it can still be sung generations after people don’t even know what the Civil Rights Movement was. Don’t know the phrase. Don’t understand why people capitalize it.

So sure. Mavis Staples hears that song and she’s saying, “How does he know me? How does he know my father?” “How many roads must a man walk down?” Did he ever walk down that road? No! But he was able to imagine himself walking down that road and understand how it would feel. What it would be about. And she’s saying, like other people have said, “How did he see me?” This is what, in “One Night in Miami,” that Kemp Powers play, that great film where Malcolm X is saying to Sam Cooke, “Here’s this white boy from Minnesota who is able to give voice to something that you can’t. How does that happen? How is this white kid from Minnesota able to express what we’re all going through and what our movement is about better than you can? Maybe even (unspoken), maybe even better than I can?” Now this is all fiction, it’s all made up, but it’s wonderful thing to make this into an historical even where two Black men are confronting themselves over a Bob Dylan song. How fantastic. How unlikely. How real. And the fact is, it has its real-world analogy, pretty much at the same time, where Huey Newton and Bobby Seale are drawing up the Black Panthers manifesto while playing “Ballad of a Thin Man” over and over and over again. And Huey Newton is posing holding a copy of Highway 61 on his chest, saying this is what it’s all about for me.

Goldberg: Could you imagine yourself writing one more book about Dylan?

Marcus: God, I hope not. No, no! You know, at this point I’m 77. I’ve spent the entire year sick. I’ve had three surgeries. I’m recovering now and I don’t know how far to being my old self I’m going to get to be. So, just the idea of writing another book about anything is not something I want to think about right now. I haven’t written anything for publication, I haven’t written anything but emails this entire year. The idea that I could just stop writing. The idea—I love to drink. It’s one of the great pleasures in my life. The idea that I could not drink for six months because the whole notion of it was repulsive, because I was so sick. That I could just give up alcohol without a second thought and it would no longer be part of my life—that’s what happened. Gone. So, who knows? I don’t know what the rest of my life is going to be like. How much of it is left. Or who I’m going to be in it. I don’t know any of this. But no, I don’t think I’ll write another book about Bob Dylan.

He has a different attitude, obviously. He announces a new tour, the Rough and Rowdy Ways Tour, which was announced as something that was going to run through 2024. That’s a long way from now for an old person. And I thought that was wonderfully audacious. Not to say, “I’ll still be alive in 2024,” but to say, “I’m still going to be on the road for 100 days out of the year and I’m going to do shows that are going to be terrible and disappointing and other shows that people are never going to forget.” Who knows? You never know what the chemistry of any given night is going to be. And you don’t. You don’t know. You can’t control it. You can’t walk out onto a stage and say, “I’m going to give the best performance of my life.” It just doesn’t work that way. You can give the worst performance of your life regardless of how hard you’re trying. You just don’t know.

Goldberg: That performing for people is such a driving force for him that it’s the Never Ending Tour.

Marcus: Well, he doesn’t need the money, so you got to figure, this is his life. This is him living his life. This is the high point; this is the challenge. “Can I do a good show even if I don’t want to. Why is it that I do a bad show when I want with all my being to do a good show?” When you don’t know what’s going to happen, night to night, and sometimes you don’t care and sometimes you care desperately.

Credit: Writer and photographer Michael Goldberg has been interviewing and photographing musicians since he was 17. He was a senior writer at Rolling Stone magazine for a decade. His writing has appeared in Esquire, New Musical Express, Creem, DownBeat, New York Rocker, Trouser Press, Musician, New West, Vibe, New Times, The San Francisco Chronicle, and other publications. He has had three novels published: True Love Scars, The Flowers Lied, and Untitled. In May 2022, Wicked Game: The True Story of Guitarist James Calvin Wilsey was published. Addicted To Noise: The Music Writings of Michael Goldberg was published on November 1, 2022.