By Bernard Zuel

It may be true that the principal calling card of Charlie Starr is that he is singer/guitarist and principal songwriter of Atlanta southern rock/Americana band, Blackberry Smoke, which is no small thing.

Seven studio albums between 2003 and 2021, a couple of live recordings, and six EPs suggests a catalogue of some heft. That five of those were top ten Country chart records – two of them making number one – with the most recent album peaking at number one on the Americana chart, indicates people are buying. And a virtually unchanged lineup since 2000 of Starr, drummer Brit Turner, bassist Richard Turn, guitarist Paul Jackson and new kid (since 2009), Brandon Still on keyboards shows solidarity alongside longevity.

Seven studio albums between 2003 and 2021, a couple of live recordings, and six EPs suggests a catalogue of some heft. That five of those were top ten Country chart records – two of them making number one – with the most recent album peaking at number one on the Americana chart, indicates people are buying. And a virtually unchanged lineup since 2000 of Starr, drummer Brit Turner, bassist Richard Turn, guitarist Paul Jackson and new kid (since 2009), Brandon Still on keyboards shows solidarity alongside longevity.

But attention should be paid to the fact that Starr is the owner of a most excellent pair of sidelevers. The kind of facial furniture that helped subdue India, forge past the Darling Downs into outback Queensland, and squired young ladies to antebellum cotillions. Long, furry and defiantly squatting on his cheeks, you don’t get those things casually. Respect.

“I didn’t do much,” demurs Starr. “I just avoided those parts of my face with a razor.”

Oh no, sir, that’s admirable. Already I can tell that he is a man prepared to dedicate himself to the task and so I feel justified in coming to Starr for advice. No, not on sideburns – at least not today – but on Georgia. No, not the one in the Caucasus, but the southern US state which gave us a president whose stature has grown every year since he left office (Jimmy Carter) and a socio-cultural giant (Martin Luther King Jr.), two of the greatest American bands (The Allman Brothers, who relocated from Florida and were claimed by their new home, and R.E.M.), some of the best or most enjoyable hip-hop (Outkast, Killer Mike, Ludacris, Young Jeezy) and peerless musical giants (James Brown, Ray Charles, Otis Redding and Little Richard).

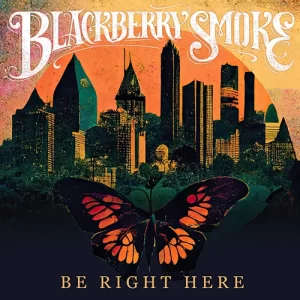

So, Mr Starr, your new album is called Be Right Here, your last record was called You Hear Georgia, so hit me with some reasons why we should move right here to Georgia.

So, Mr Starr, your new album is called Be Right Here, your last record was called You Hear Georgia, so hit me with some reasons why we should move right here to Georgia.

“Oh, I don’t have any reasons why you should move to Georgia. Be right here means be right here in your heart,” he says, before conceding somewhat. “Actually, Georgia is great. Atlanta specifically is great. It’s a very large city, there are now three Michelin starred restaurants – [the third] just happened a month ago.”

Don’t let the sideburns and rocking barroom sound fool you into making cheap assumptions, Starr knows his culinary onions.

“I like to cook, I like good food and my wife was in the restaurant business for years so we have friends who are chefs,” he says. “We have one good friend that’s a chef that’s really successful: he has lots of restaurants, lots of – what’s the word they use? – ‘concepts’, and he is also a guitar collector. So we are nerds about all that.”

To that end, almost screaming “here’s one I prepared earlier”, on the wall over his shoulder can be seen a Flying V guitar, and there is a Gibson Explorer nearby. The man likes his angles. But on a sombre note, tempering the enthusiasm for Atlanta is the fact that “we don’t have a good sports team, so don’t get excited about that”, though he will grant that the Braves aren’t doing so badly. “They blew it in the play-offs, but that’s nothing new.”

In his home, surrounded by favourite tools of the trade, a few steps from an oft-used kitchen and an easy drive away from other fine fare, it’s easy enough to grasp the underpinnings of the Blackberry Smoke album concept to be present, to understand and be yourself. However, how much of knowing himself and being himself is identifying with where he is from?

“I don’t know about that for myself, because we spend most of our lives elsewhere,” Starr says. “But I’ve spent many a mile in some sort of vehicle and put on music from the south-eastern United States to take myself home. So I guess it is a huge part. When we get scared and uncomfortable, we want to feel home, going back to the thoughts and memories of childhood and stories, whether it’s literature or music or whatever.”

From the outside, with all the assumptions and ignorance that comes with that, it can seem as if the South generally, and the south-east/Georgia specifically, is tied to its past and its stories. Does he feel that as a storytelling songwriter? Does he have a drive to tell stories that draw from this past?

“Maybe. I don’t know that I feel the need to but it’s definitely where I feel the most comfortable. I think I heard John Mellencamp years ago say write about what you know and that’s what I know, or I think I do,” he says. “But there’s also to me a very romantic tradition, a storytelling tradition – and I’m not in any way including myself in this category – in this part of the country. Harper Lee is buried here, Truman Capote is from Alabama, and there’s this whole cast of amazing Southern writers, contemporaries now, that I can’t stop reading. Or I can’t stop soaking up what they are putting out there.

“I have a good friend named Michael Farris Smith who is a great novelist, and I said hey man I’m just trying to do what you guys do but in three minutes at a time, in the key of G.”

Like Irish writers, literary and musical, it does feel as if Southern writers don’t feel that they have to separate the past and the present – one informs the other.

“I don’t know that I’m good at that but I have so much respect for people who can do that, like Shane MacGowan,” says Starr. “All those Pogues songs, they feel like they are 300 years old, the stories that he’s telling. Oh to be able to do that.”

Except he does do that: his characters working in lives and experiencing conditions that aren’t locked into a timeframe.

“I noticed not long ago I was listening to someone and it was a similar feeling, like I can see this, and then all of a sudden he mentions a cell phone in the lyrics, and I was like, oh, ok, it’s modern,” Starr chuckles.

The downside to being associated with a tradition is that people can make assumptions about your approach or your thinking or your attitudes, whether it’s a preference for fast food at a roadside diner, basic boogie or narrowminded social values. What should we not say, or not assume of a Southern man generally, a Georgia man more specifically, and Starr in particular, when we meet them?

“I don’t know. None of that applies to me, personally, really, because nothing is off limits. Assumptions abound,” he says. “But I will say this, and I guess it can be the elephant in the room when you talk about the South, and specifically Atlanta, Georgia: there are no burning crosses.

“I’m 49 years old, I didn’t grow up around a bunch of racist people. Even watching movies, even as an adult, it was really easy to cast these toothless bumpkins in some dramatic movies as being Southerners. It’s very cartoonish. You can go to small towns just about anywhere in the United States, not specifically in the South – and I learned this when I started to travel – and find hatred. Not just about skin colour, but about difference: cultures, the way you dress, the length of your hair. I was fortunate not to be surrounded by what you see in movies.”

Hey, sitting here in Australia with an alternative Prime Minister prone to race baiting and media culture primed for angertainment, I’m certainly not in a position to be talking down to or assuming levels of prejudice are worse in another country.

“One thing that I’ve noticed, fortunately, even as I would dig into the history of music is that music and art would seem to be a safe space as far as hate goes, in a lot of ways and a lot of different stories,” says Starr. “I remember being fascinated by stories like Louis Armstrong and Jimmie Rodgers recording together in the late ‘20s, and Lonnie Johnson and Eddie Lang – two guitar players, one white guy, one black guy – playing together when you would think it was unheard of.

“And then fast forward to the ‘60s and the Allman Brothers have Jaimoe (drummer/percussionist John Lee Johnson) join their band, and they wind up with a black drummer in arguably the first Southern rock ‘n’ roll band. In Macon, Georgia, of all places, which is a very small town and is not a place you would think that there would have been an interracial band in 1969.”

Same same but different?

“Duane and Gregg both told stories about not being able to eat in some places with Jaimoe in the band, but none of us have experienced things like that; it almost seems like a fairy tale, a horrible fairy tale. But it’s not,” he says. “My stepdad is from Haiti and he moved here in 1968 and I asked him once, ‘did you experience racism in New York City in 1968?’ and he said ‘I didn’t. I knew it was going on because the United States was in a serious state of upheaval, but it was nothing compared to what I was leaving.’ Haiti was basically on fire.

“And I asked him specifically if it felt harder then then it does right now and specifically 2020 with Covid and it seemed like the world was on fire again, and he said ‘no, this is nothing compared to the late ‘60s where there were Kent State students being shot and killed in broad daylight’. So, perspective I guess.”

You can purchase Be Right Here right here: Be Right Here