By Michael Goldberg.

Improbable as it might seem at first, Dylan has recorded an album of songs associated with Frank Sinatra – and it’s damn good.

I hated Frank Sinatra. As a teenager, Sinatra, who was my mother’s favorite singer, represented my parents’ middle class world, a world I was desperate to escape. I wrote Sinatra off as one of those puppets, a Hollywood-invented pop star who sang Tin Pan Alley love songs, the kind that rhymed moon and June.

Silly love songs. That was what Frank Sinatra was all about. Trivial.

And worse still, I read that he hated rock ‘n’ roll.

In 1957, in the Paris magazine Western World, Sinatra called rock ‘n’ roll “the most brutal, ugly, degenerate, vicious form of expression it has been my displeasure to hear … It fosters almost totally negative and destructive reactions in young people. It smells phony and false. It is sung, played and written for the most part by cretinous goons and by means of its almost imbecilic reiterations and sly, lewd—in plain fact dirty—lyrics, and as I said before, it manages to be the martial music of every sideburned delinquent on the face of the earth. This rancid smelling aphrodisiac I deplore.”

So yeah, for me Sinatra was Public Enemy #1.

Sinatra was, in my opinion, the polar opposite of my idol, Bob Dylan, the brainy rock ‘n’ roll star who had in rapid succession released three of the greatest albums ever: Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde.

Dylan wrote his own songs, sang with a voice like no other, was a poet, brought the art of songwriting to a level it had never previously reached and was the hippest of the hip.

In 1965, while Sinatra was singing retro pop like “The September Of My Years” and “Last Night When We Were Young,” Dylan was spitting out such modern cubist masterpieces as “Ballad Of A Thin Man,” “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and “Like A Rolling Stone.”

Sinatra was ancient history, the pop singer my mother’s heart beat fast for during her teenage years as a bobby soxer.

I had no interest and no time for Frank Sinatra.

But 23 years later, in 1988, thanks to Beach Boy Brian Wilson, my attitude towards Sinatra changed. I was on assignment for Rolling Stone, writing a feature story about Wilson, who had a debut solo album about to be released. I was hanging out with Wilson at his townhouse in Malibu, and I was checking out some of his favorite CDs, which included recordings by Randy Newman and Phil Spector. There was one by Frank Sinatra, possibly In the Wee Hours or it might have been September Of My Years. Whichever it was, I listened to it there at Wilson’s place, and I opened up to Sinatra. I heard him for the first time.

I came to appreciate Sinatra, and the songs he sang, and I came to dig the often sentimental arrangements provided by Nelson Riddle and others.

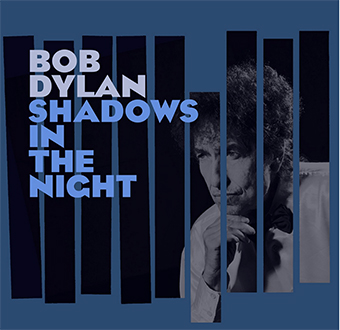

Still, when I learned that Bob Dylan, BOB DYLAN, had recorded Shadows In The Night, a full album of songs previously recorded by Sinatra, my initial reaction was that of my 15-year-old self: horror.

Dylan singing those songs? Those corny Tin Pan Alley songs? How could he?

Still, this was Bob Dylan. I’d jumped to conclusions in the past, and then changed my mind once I really listened. So I would give this one a chance.

When I heard “Full Moon and Empty Arms,” which in May of 2014 was streaming off Dylan’s website, I found it moving. Beautiful and tragic.

And more. For this wasn’t Dylan covering Sinatra. This was different. Dylan had made the song his own. Most prominently, beneath his blue vocal, a mournful pedal steel guitar like fog rolling in, as Dylan once said of the Staple Singers “Uncloudy Day.”

I saw Dylan perform at the Paramount Theater in Oakland last October and heard him encore with “Stay With Me,” another song from Shadows In The Night, and the deal was sealed. I could imagine Dylan singing an album of old school songs, and I could imagine it as a Bob Dylan album.

Well now it’s here, and it’s wonderful.

In fact, if anything, I wish it were longer. At about 33 minutes, every time it ends I crave another couple of songs. And since Dylan cut 23 songs, according to engineer Al Schmitt, who recorded the album at Capitol Records Studio B in Los Angeles, there must have been others worthy of inclusion. Oh well. Maybe we’ll be lucky and get a volume two.

In a statement included in a press release announcing the album, Dylan said:

“I’ve wanted to do something like this for a long time but was never brave enough to approach 30-piece complicated arrangements and refine them down for a 5-piece band. That’s the key to all these performances. We knew these songs extremely well. It was all done live. Maybe one or two takes. No overdubbing. No vocal booths. No headphones. No separate tracking, and, for the most part, mixed as it was recorded. I don’t see myself as covering these songs in any way. They’ve been covered enough. Buried, as a matter a fact. What me and my band are basically doing is uncovering them. Lifting them out of the grave and bringing them into the light of day.”

So don’t be fooled by the fact that these songs were written by other writers and think that this is a “covers album,” or a standards album, or simply a collection of other people’s songs that Dylan is interpreting.

No, this is a Dylan album, a Dylan album recorded by a man in his seventies, a man who has, as we know, had serious love relationships, who has known romance and heartache and the pain of a once cherished marriage that went to pieces. Dylan knows the emotions in these songs. He’s lived them.

This is a mature album that deals with desire and regret, romance and disappointment, moral weakness and, finally, death. It’s a heavy album, and Bob Dylan brings a gravity to these songs, a version of the gravity he brought to an album he recorded so long ago that mostly contained songs written by other writers. I’m thinking of his 1961 debut, Bob Dylan, an album of songs about some of the same themes that run through Shadows In The Night.

Yet where the Dylan who sang the songs on Bob Dylan sang with the strength of a young man with his life still in front of him, I imagine the Dylan singing Shadows In The Night compromised by romantic dreams that didn’t pan out, by betrayals of one sort or another, some inflicted on him, some inflicted by him, sitting in a dark bar, on his third or fourth Jack Daniels, reflecting on all that has slipped through his fingers.

The album opens with a breathtaking version of “I’m A Fool To Want You,” a song first recorded by Sinatra in 1951, but it’s the second version Sinatra cut in 1957 with an arrangement by the great Gordon Jenkins and which was included on the Sinatra album Where Are You? (four of the ten songs on Dylan’s album are also on that Sinatra album) that inspired Dylan to record it.

With this song, the mood and sound of the entire album is immediately established by Dylan’s band members – Donnie Herron’s pedal steel, Charlie Sexton’s sensitive electric guitar along with Tony Garnier’s upright bass – and Dylan’s yearning yet forsaken vocal.

“I’m a fool to hold you,” Dylan sings. “Such a fool to hold you, To seek a kiss not mine alone, To share a kiss that the Devil has known.”

This is a song about succoming to temptation, and it’s the first song on the album. You could say it sets the theme, and it shows just how far Dylan has come from the days when he mocked an ex-love with a “new boyfriend” who the singer sees “makin’ love to you, You forgot to close the garage door” in 1966’s “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat.” Now he doesn’t care about the “new boyfriend.” He’s willing to take this woman on her terms, whatever they are – even if he has to share her with the Devil himself.

This song once again establishes Dylan’s authority as a singer, and his singing throughout the album is remarkable. In fact, I think Dylan proves what a genius singer he is time and time again on Shadows In The Night. One of those magic moments comes when he sings the third verse of “I’m A Fool To Want You.”

When Sinatra sang this song in 1951, he sang each of the four verses once. But in 1957, after completing the four verses, he sang the last two verses again, only with a bit more heartache. Dylan also sings those two verses twice, and it’s the second time through where he trumps Sinatra.

These are the lyrics Dylan sings:

“Time and time again I said I’d leave you

Time and time again I went away

But then would come a time when I would need you

And once again these words I had to say

Take me back, I love you

I need you

I know it’s wrong, it must be wrong

But right or wrong I can’t get along

Without you”

The first time through Dylan sings it fairly straight, nuanced but for the most part with equal weight on each word, although when he sings “Time and time again,” he holds on “again” in a way that makes us feel just how many times he’s been through this, and then with the next line – “Time and time again I went away” — there’s such a wistfulness to his delivery.

The second time around is a whole other deal. When he sings “Time and time again I said I’d leave you,” he stretches out the word “said” in this remarkable way that conveys such a weariness, before he sings “I’d,” and stretches the words “leave you,” and in those words and the passing of time as he sings them, you feel all those times he said he was leaving, all that struggle against a desire that is so powerful he can’t deny it, which is driven home when he pauses on “need you,” the last words of the third line of that verse.

“When Dylan sings the final verse, ending with “But right or wrong I can’t get along without you,” we hear the voice of a man caught in a trap with no way out. It’s Jimmy Stewart in “Vertigo” obsessed with Kim Novak, or Fred MacMurray in “Double Indemnity” willing to do anything for Barbara Stanwyck.

The music across the whole album is strangely beautiful. There’s almost a western swing quality, only that’s not it. The steel guitar brings to mind the Hawaiian islands, only that’s not it either. As I listen I see Orson Welles’ “Lady From Shanghai,” the doomed romantic scenes on the boat with Michael (Welles) and Elsa (Rita Hayworth) and the scene on the beach where Elsa and her husband Arthur (Everett Sloane) and George (Glen Anders), all of them drunk, go at each other, as Michael puts it, like sharks inflamed by the smell of blood.

I think what Dylan has done here is taken the idea of the Nelson Riddle and Gordon Jenkins orchestrations of Sinatra’s versions and loosely interpreted them using his five piece band, a band that typically plays a Dylanesque Americana, and so we get the drama that was built into these songs, which were written between the 1920s and the early 1960s, and yet we’re hearing musicians (Dylan’s band including Stu Kimball, guitar, and George C. Receli, percussion, along with a handful of horn players) playing instruments associated with jazz and/or country music.

It makes for a retro sound, only I don’t believe any sound like this existed back in the past these songs seem to reference. So we are thrown back to an imaginary time, a romantic time which is appropriate since these songs originally dramatized in the extreme way that songs often do, and that old school Hollywood films did, the emotions we experience in our own attempts at love.

While this is a real album, one that works as a coherent whole and not a collection of unrelated songs, one that you listen to from start to finish, several other songs in addition to “I’m A Fool To Love You” are standouts.

“Full Moon and Empty Arms” is one of those, and when you hear it in the context of this album, coming as it does after the Rodgers and Hammerstein-written standard, “Some Enchanted Evening,” it hits hard in a way it didn’t when I first heard it last May. This one, like “I’m A Fool For You,” has the otherworldly sound of Dali’s surrealist dream sequence in Hitchcock’s “Spellbound,” if you could turn that scene into music.

“What’ll I Do?,” written by Irving Berlin in the 1920s, is sadly beautiful. When Dylan sings the lines, “What’ll I do with just a photograph, To tell my troubles to, When I’m alone with only dreams of you, That won’t come true,” you feel the singer’s despair.

And then there is “Autumn Leaves.” Also from Sinatra’s 1957 Where Are You? album, Dylan’s version is perfect. This is another song about remembering a love that went south. The singer’s lover left him, and he can’t forget her.

“I see your lips, The summer kisses, The sumburned hands, I used to hold.”

The singer is broken and lost, and you hear that in Dylan’s voice throughout the song, and most poignantly when he sings the final lines:

“But I miss you most of all, My darling, When autumn leaves start to fall.”

The album ends with “Lucky Old Sun,” which as Dylan sings it is more a spiritual than a pop song. It was originally a hit for Frankie Laine in 1949. Dylan performed it live 27 times beginning in 1985 at Farm Aid. By opening the album with “I’m A Fool To Love You,” and ending with “Lucky Old Sun,” Dylan makes it clear that the story this album tells is, in theatrical terms, a tragedy.

“Lucky Old Sun” is a song about death – or at least a wish for death. The singer is asking God to take him to heaven. “Dear Lord above, can’t you know I’m pining, tears all in my eyes, Send down that cloud with a silver lining, lift me to Paradise.”

The song is a hope for something better than having to “work like the devil for my pay.” A hope that there is an after-life. The singer believes in a God who can, if he so chooses, “show me that river, take me across, wash all my troubles away.”

It is the perfect ending to this album, an album I never could have imagined Dylan making, but am so glad he did.

Dylan, man, he’s the best.