By Steve Bell.

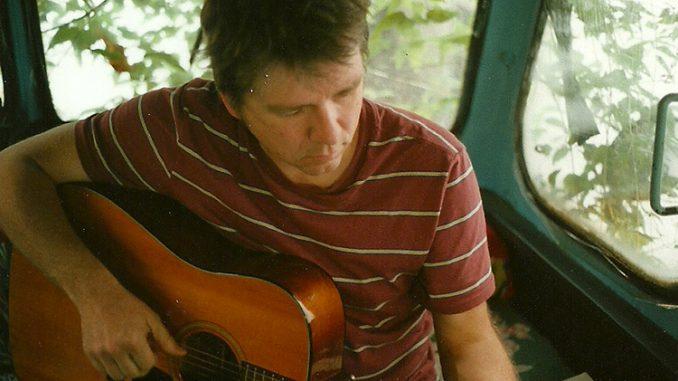

After decades on the road touring throughout Australia and the wider world, much-loved indie-pop singer-songwriter Darren Hanlon has become widely renowned as one of the finest musical exports ever to emanate from his birthplace in the Queensland town of Gympie. Yet his new sixth solo album Life Tax has its genesis far further south, down in Melbourne.

Living in the southern capital for a stretch in the pre-COVID times – and having ingratiated himself with the custodians of the local Uniting Church Hall in Northcote – Hanlon was soon utilising the space as a studio in which to both conceive and record Life Tax, alongside a cadre of talented friends from the thriving Melbourne scene.

They emerged with a sparse, stripped-back collection of acoustic-based songs – one still showcasing a pleasing diversity of feels – whose quiet nature allows focus to fall on Hanlon’s trademark wry observational lyrics and charmingly unaffected delivery, the results as laidback-yet-touching as ever.

“It’s definitely more of a gentle record,” the singer smiles. “Because even though we were in a hall I had to be mindful of the neighbours. It’s getting really gentrified around there.

“You know that process where it becomes a really interesting artistic suburb over time and then all the rich people want to live there, then they complain about the noise? It’s one of those deals, so I had to be really careful and kind of hushed-ly, quietly squirrel away in there with the songs, and I think that gave it a bit of a feel. But also the acoustics of the place played a role: I dunno, I just really like the way the it turned out sonically, you can feel the space in the vocal reverb.”

As with much of Hanlon’s best work these songs contain a strong autobiographical bent, the powerful ‘Lapsed Catholics’ in particular using narratives lifted directly from his own life to craft a powerful social treatise.

“I grew up pretty heavily in the Catholic faith up in Queensland – it’s like a football team, you’re born into it and you don’t question it too much,” he laughs. “I’m a shocker – or I was when I was younger – in terms of not questioning stuff, I had a pretty stable upbringing so I just went with the flow.

“It wasn’t until I left home that I started questioning things, and essentially the last straw was the anti-gay marriage petition that got handed out at the Mass – there were many cracks in the facade before that, but that was the thing that clutched it.

“I just couldn’t understand how the Catholic Church could take that position, it just staggered me. I was still an altar server up until I left high school, and still went to church when I went to university, but I kind of just lost the faith over the years after that. It was kind of meant to be a protest song, but it ended up a way more personal telling of my story in terms of the Catholics”.

Hanlon had spent the best part of a decade playing in and with a succession of great bands before eventually turning his attention to penning his own tunes, and although he makes the craft seem completely effortless he admits to a lot of toil taking place behind the scenes.

“I slave over it,” he reflects. “Some of the narrative songs I write are almost like a breather in-between the harder ones. With the other ones – the mysterious ones – there’s a kind of pain involved in getting some of them out. You know that they’re in there – you know that there’s something in there.

“But it’s the eternal mystery of songwriting – and a conversation I have with lots of my friends who are songwriters – how do you keep doing it? And how do you keep the quality, and how do you know if the quality’s slipping? If you knew exactly how to do it I would do it all the time, but the best I can do at this stage is just kind of turn up and just be available in case a song comes to you. But some of them are really painful, I’d say.

“I did come to songwriting late – I’d always wanted to be one, but didn’t really have the confidence to be one. All of my heroes were songwriters, but especially because I was surrounded by all these amazing songwriters. I was in these bands where I was a guitarist and I didn’t need to be one at that stage because all these people were doing it better than I could have at the time, so I kind of just sat back and watched and learned… a bit!

“By the time The Simpletons were done and I’d done a little bit with The Lucksmiths and was touring with Mick Thomas I kind of got the courage to start doing it myself, I suppose. Then I had a near-fatal electrocution at a Mick Thomas gig – he totally saved my life – and that gave me even more courage: I thought, ‘Okay, if I’m going to die for rock’n’roll, it might as well be mine!”

You can purchase Life Tax here: https://flippinyeahindustries.bigcartel.com