The mysteries of the ’65/’66 recordings revealed (maybe)!

How deep can you go into a song? As Greil Marcus’ two recent books, The History of Rock ‘N’ Roll in Ten Songs and Three Songs, Three Singers, Three Nations, reveal, there’s no limit. Alice falling down the rabbit hole to discover a subterranean landscape dotted with surreal characters such as the “mad” Hatter, the White Rabbit and a hookah smoking caterpillar, has nothing on Marcus, who takes a song as deceptively simple as Bascom Lamar Lunsford’s 1928 recording “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground” and finds lost continents in its strange lyrics.

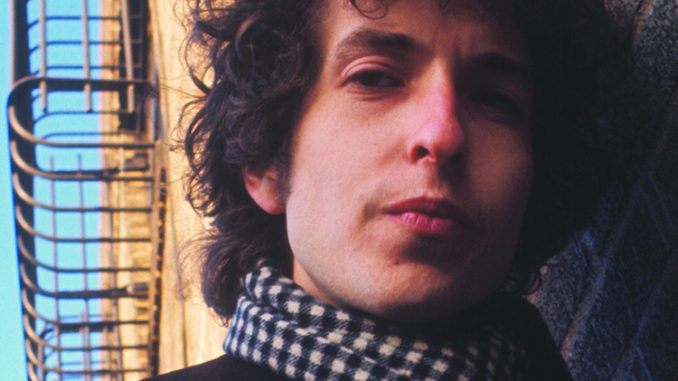

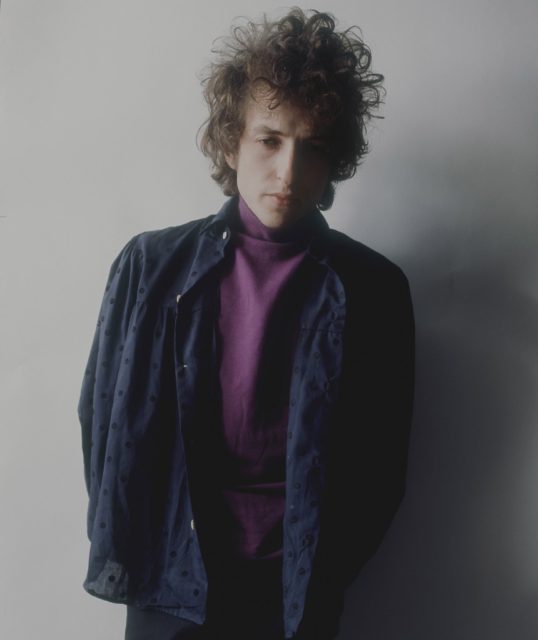

It’s no coincidence that Marcus is obsessed with Bob Dylan, the master of bottomless songs; Marcus has written entire books delving into what he hears in Dylan’s recordings. He’s been digging Dylan even longer than I have, and I’ve been in the Dylan Zone for 50 years.

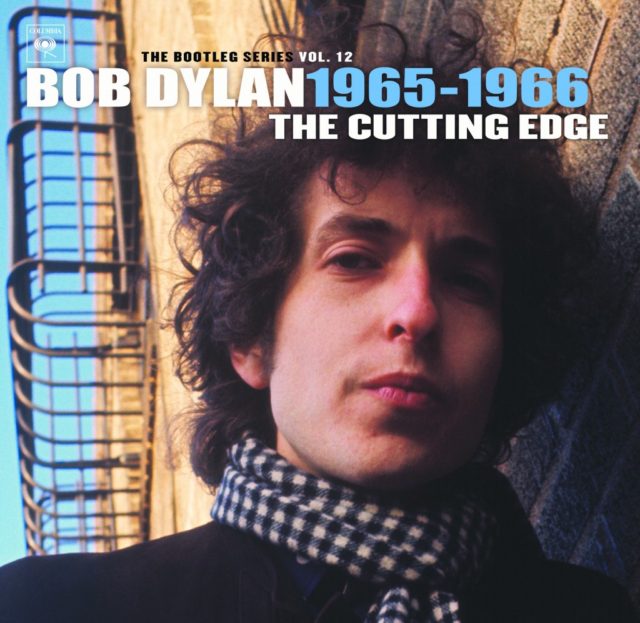

I read Three Songs… just prior to the arrival of the Collector’s Edition of The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12, a pricey ($599) 18 CD set that contains “every note recorded during the 1965-1966 sessions,” according to a Sony press release, as well as a CD of recordings made in hotel rooms while Dylan was touring during those years that include some wonderful, apparently never completed Dylan originals. Now if only they’d released all the live recordings, but perhaps that’s in the works, hint, hint…

Just so you understand, 18 CDs translates to over 18 hours of music. Close to a full day and night’s worth of Bob Dylan recording the albums that set a new standard for what rock ‘n’ roll records could be, and to this day influence musicians the world over. Many of the songs on those albums are deep. They are songs with trap doors and secret passages, songs that confound, defy, deny, and mystify.

Listen to the 2CD version here:

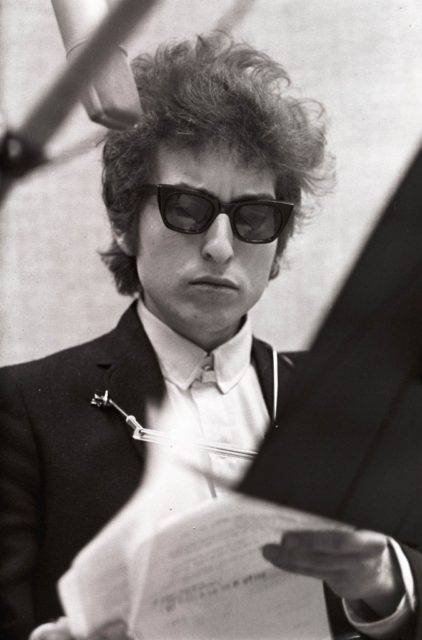

Here was an opportunity to explore not only the depth of the songs recorded during the sessions that produced Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde, but a rare look at the creative process of an artist at the top of his game: Bob Dylan attempting many takes of some songs, radically changing his approach from take to take in some cases while making minor changes in others. Dylan cracking jokes and cracking up.

“Like a Rolling Stone” Turned My World Upside Down

I’d just turned 12 the first time I heard Bob Dylan. His voice from the car radio singing his Top Ten hit as my mom drove me somewhere in the summer of ’65. I had been listening to rock music – including songs by The Beatles and the Stones and the Beach Boys and the Lovin’ Spoonful and The Byrds – for a year or so. This was different. This was “Like a Rolling Stone.” This was the ecstatic transmuted into a six minute, thirteen second recording.

This was “Like a Rolling Stone.” This was the ecstatic transmuted into a six minute, thirteen second recording. That song changed me.

That song changed me. There was rebellious fury in Dylan’s voice, in how he sang his Beat lyrics about class privilege and the fall from grace, in how he sang a song that managed to say what it took F. Scott Fitzgerald a whole novel, “The Beautiful and the Damned,” to say. But though I related to the lyrics, what slayed me was the music. And more. Dylan’s voice and the sound of that record made me know one didn’t have to go along with the rules society imposed, that there was another way to live. That it was possible to be fully alive, and not sleepwalk through life.

Or as Dylan sang, “It’s life, and life only.”

So for me, perhaps the pièce de résistance here are the complete studio recordings of “Like a Rolling Stone,” all 20 of them. As it turns out you can also get them on the much less expensive 6 CD Deluxe Edition; for many that will be the way to go. And let me be clear here: the 18 CD set is only for the total obsessives, the immoderates, of which I am one.

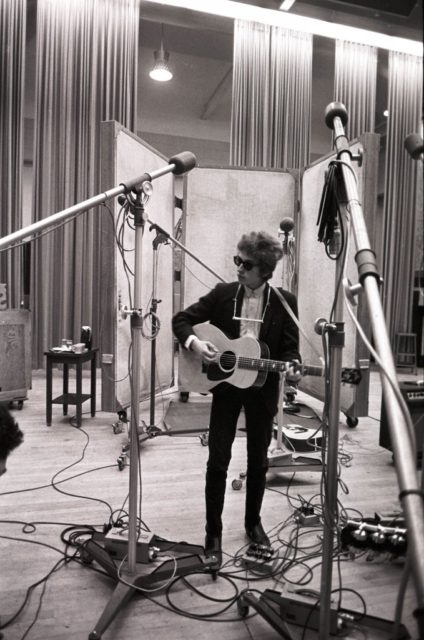

Listening chronologically to all the takes of “Like a Rolling Stone” provides a kind of fly on the wall view of how Dylan and a crew of extremely talented musicians – on the first day the song is attempted: Michael Bloomfield on guitar, Al Gorgoni on guitar, Paul Griffin on organ, Frank Owens on piano, Joseph Macho Jr. on bass and Bobby Gregg on drums; and on the second day: Bloomfield, Griffin on piano, Macho Jr., Gregg and the addition of Al Kooper on organ and Bruce Langhorne on tambourine – succeed against all odds in recording one of the great rock ‘n’ roll records.

In the epitaph to his 2005 book, Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads, Greil Marcus describes in detail what happened during the “Like a Rolling Stone” sessions based on listening carefully to the session tapes. When I read his book in 2011, I wanted so bad to hear what Marcus had described. His writing made me feel as close to being there in the studio as I imagined one could ever get.

I was wrong. Miracle of miracles! Now we can actually listen for ourselves, we can get even closer, we can listen in on a historic moment in rock history, when everything fell apart, then came together for those six minutes, 13 seconds – musicians, producer, singer, words, melody – and fell apart all over again.

As Marcus has written, and as is clear when you listen, nothing was going right. When they start in on the song at Columbia Studio A in New York, near the end of a long session on June 15, 1965 that has already found these musicians cutting ten takes of “Phantom Engineer” (the song that was retitled “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry”), and seven takes of “Sitting On a Barbed Wire Fence,” Dylan admits, “My voice is gone.”

Soon they pack it in, only to pick up where they left off the next day, which is to say, during the first few takes the song remains out of reach. It doesn’t have a hook to pull you in from the first notes, Michael Bloomfield hasn’t found the guitar riffs the song needs, Al Kooper is searching for what to play on organ, and Dylan hasn’t found the right tempo or pacing, nor settled on how he should sing his bitter words.

As I listened, first to the January 15 recordings, then the first few takes cut the next day, lost in the moments of those takes, despite knowing that Dylan and the band had eventually pulled it off, I started to have my doubts. It was as if they’d taken a wrong turn and were miles from the song. And then, amazingly, with the fourth take they hit pay dirt. Only they weren’t sure, and recorded ten more takes, once again losing their way.

Here’s Marcus writing about what happened:

“No matter how timeless ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ might turn out to be, what happened over the two days of recording sessions makes it clear that had circumstances been even slightly different – different people present, a different mood in the studio, different weather in the streets outside, a different headline in the morning paper – the song might never have entered time at all, or interrupted it. … ‘Like a Rollling Stone’ is a triumph of craft, inspiration, will, and intent, regardless of all those things, it was also an accident. Listening now, you hear most of all how much the song resists the musicians and the singer. Except on a single take, when they went past the song and made their performance into an event that down the years would always begin again from its first bar, they are so far from the song and from each other it’s easy enough to imagine Bob Dylan giving up on the song, no doubt taking phrases here and there and putting them into another song somewhere down the line but never bothering with that thing called ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ again. Following the sessions as they happened, it can in moments be easier to imagine that than to believe that the record was actually made… That is what makes an event, after all: it can only happen once. Once it has happened, it will seem inevitable. But all the good reasons in the world can’t make it happen.”

Dylan Goes Electric

The Cutting Edge is about Dylan’s move to working in the studio with musicians and electric instruments. Sure he played rock ‘n’ roll in his teens, but this was different. Now he was a folk music phenomena and a professional musician who had recorded four albums and written a major hit, Peter, Paul and Mary’s 1963 version of “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Producer Tom Wilson recorded Bringing It All Back Home, plus the first two Highway 61 Revisited sessions, which resulted in one recording, “Like a Rolling Stone,” that was released at the time). For still mysterious reasons, Wilson was replaced by producer Bob Johnson, who cut the rest of Highway 61 Revisited, “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window” and all of Blonde On Blonde. Both men recorded Dylan and the the musicians he was working with live in the studio, which was how most records were made back then.

In the early days of Dylan’s studio recording he would cut just a take or two of most songs. That changed. By the time he worked on Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde, he was recording as many as 30 takes, as was the case with “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?.”

It was in February of 1964, during a 20-day Kerouac-influenced road trip across the U.S., with Dylan working on songs in the back of a station wagon, that he heard The Beatles on the car radio and decided it was time to go electric. It wasn’t the first time he’d heard The Beatles, but this time he had a revelation.

“We were driving through Colorado, we had the radio on, and eight of the Top 10 songs were Beatles’ songs. In Colorado! ‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand,’ all those early ones,” Dylan said during a 1971 interview with one of his biographers, Anthony Scaduto. “They were doing things nobody was doing. Their chords were outrageous, just outrageous, and their harmonies made it all valid … But I kept it to myself that I really dug them. Everybody else thought they were for the teenyboppers, that they were gonna pass right away. But it was obvious to me that they had staying power. I knew they were pointing the direction of where music had to go.”

Back in New York in March, Dylan rented an electric guitar. In April he dropped acid for the first time, and while he has denied that drugs impacted his songwriting, it’s hard to imagine that to be the case. Touring England in May he spent time with The Beatles and, of course, he was hearing records by the Rolling Stones and The Animals on the radio including a rock version of “House of the Rising Sun,” the folk song he’d recorded on his debut. Though Dylan recorded another acoustic album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, in June of 1964, the songs were more personal, mostly about relationships, setting the stage for what would come next.

Bring It All Back Home

Dylan was used to going into the studio, doing a take or two of a song, and moving on. He recorded his first album during two sessions. While he spent many sessions spread over a one year period recording The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, and six sessions on The Times They Are A-Changin’, he recorded Another Side of Bob Dylan in it’s entirety during one evening in June 1964. And even with Freewheelin’, most songs were cut in a take or two.

So when Dylan started making rock records with studio musicians he initially approached it the way he’d approached his solo records. He recorded the entire Bringing It All Back Home album, plus additional songs, during three days of sessions.

On disk one of The Cutting Edge there is an exquisite solo acoustic version of “She Belongs To Me” (Take 1, Jan 13, 1965). While the setting and approach is akin to what Dylan was doing on his “folk” albums, the words, which started to have a surreal quality, are pure rock – or at least rock as Dylan would soon remake it. The pairing of opposites in the lines “she can take the dark out of the night and paint the daytime black” is an approach Dylan would use again and again, just one example being some of the lyrics for the Blonde On Blonde song, “Stuck Inside Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” as well as the Bringing It All Back Homesong, “Love Minus Zero/No Limit,” where he famously sings, “There’s no success like failure, and failure’s no success at all.”

All the recordings made for Bringing It All Back Home mostly fit on two The Cutting Edge CDs, but those CDs overflow with tracks worth hearing.

Some favorites:

• An acoustic “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (Take 1, Jan. 13, 1965) that due to Dylan’s crude accompaniment on guitar sounds totally punked out. Yeah yeah yeah this is on Bootleg Series, Vol. 1-3, but it sounds quite different in the context of this collection, followed a bit later on CD #1 by Dylan’s reinvention of the song as a swingin’ Chuck Berry groove with Beat scene poetry (Takes 1 & 3, Jan, 14, 1965).

• An acoustic “Outlaw Blues” (Take 1, Jan. 13, 1965) gone rock ‘n’ roll, and, a bit later on CD #1, remade as an electric hard blues that’ll rip your head right off (Take 2 remake, Jan. 13 1965).

• The previously unreleased and incomplete “You Don’t Have To Do That,” a breakup song with a so-so lyric but a strong vocal and melody. Dylan sings one verse, then cuts it off because, he says, he wants to do it on the piano. Which apparently never happened. Too bad (Take 1, January 13, 1965).

• For the seemingly simple “On the Road Again,” Dylan and his studio band need 17 takes – at that point far and away the most times Dylan had attempted a song in the studio — to deliver a killer recording of this rockin’ blues, which by the final take includes the now classic opening harp note followed by a brief unforgettable guitar riff. Great example of how a song that seems to bog down take after take can suddenly come alive when the rhythm, supporting musicians and Dylan’s vocal gel (Take 13, January 15, 1965).

Of note: Dylan needs just two takes to record the devastating seven minutes, 29 seconds long “It’s All Right Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” (Take 2, January 15, 1965), one for the equally incredible five minutes, 20 seconds “Gates of Eden” (Take 1, January 15, 1965), two for “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” (Take 1, January 15, 1965) and one for the totally rockin’ “Maggie’s Farm” (Take 1, January 15, 1965).

Highway 61 Revisited

In mid-January of 1965 Dylan completed the recording of Bringing It All Back Home. His life was now accelerating. The high-profile Richard Avedon photographed him on February 10 and a week later he was interviewed on “The Les Crane Show” in New York where he performed “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” and “It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding,” with accompaniment by session guitarist Bruce Langhorne. In late March Bringing It All Back Home was released and “Subterranean Homesick Blues” went Top 10 in the UK. Dylan played some gigs in March in the U.S. with Joan Baez. In early April The Byrds folk-rock version of “Mr. Tambourine Man” was released and became a #1 hit in the U.S. and the UK. In late April and early May Dylan did the acoustic tour in England that was filmed by D. A. Pennebaker for the documentary Don’t Look Back. A great scene in that film shows Dylan, already looking like a rock star, not a folkie, standing outside a music store in Newcastle digging the electric guitars in the window.

After a vacation in Portugal with his soon-to-be wife Sara Lownds, followed by the recording of a couple of BBC shows in London, Dylan returned to New York and on June 15, 1965, showed up at Columbia Studio A to begin recording his first full-blown rock ‘n’ roll album, Highway 61 Revisited, just five months after completing Bringing It All Back Home. “My words are pictures and the rock’s gonna help me flesh out the colors of the pictures,” Dylan told a friend.

This time Dylan wasn’t going to get away with one or two takes of a song. What he started with Bringing It All Back Home is taken to a whole new level over the course of seven days of sessions spread across June, July and early August. Recording ends on August 4, 1965 and Highway 61 Revisited is released at the end of the month, on August 30, 1965, and soon charts at #3 in the U.S. on the Billboard Top 200 and at #4 in the UK.

Nearly six CDs in The Cutting Edge are devoted to Highway 61 Revisited. In addition to the 20 takes of “Like a Rolling Stone,” there are many fascinating tracks from the Highway 61 Revisited sessions.

Take 1 of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh…” (Take 1, June 15, 1965) starts with Dylan on piano. Soon the band falls in behind him and they get a good groove going. Among the lyrics that Dylan sings during multiple takes that day, but that he later changed, “Well I just been to the baggage car where the engineer been tossed, I stomped on 40 compasses, god knows what they cost.” Take 8 (June 15, 1965) is taken at breakneck speed, the train nearly going off the tracks. And Take 9 (June 15, 1965), released on the Bootleg Series Vol. 1-3, is even better.

When Dylan returns to the studio on July 29, things start off with a killer take of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh…” (Take 1, July 29, 1965) that, unfortunately, falls apart all too soon. It’s a raucous call-and-response blues with Dylan singing a line and Bloomfield firing back with a blistering, wiry, switchblade riff. They take a break and cut 12 takes of “Tombstone Blues,” including the one that ends up on the album (Take 12, July 29, 1965), and then they return to “It Takes a Lot to Laugh…” only this time it’s at a slow, lopping pace, and sounds terrific. Now they’ve got the acoustic guitar part that starts the song, and the barrel house piano running through it. Dylan’s refined the lyrics too. In place of Bloomfield’s searing blues guitar is much more restrained playing. Perfecto! In total, 17 takes of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry,” in which the song evolves from a blistering blues-rocker to the slow-paced ballad heard on Highway 61 Revisited (Take 4, July 29, 1965).

• Twelve takes of “Desolation Row.” My favorite here, other than the take that ended up on the album (Take 5, August 4, 1965), is the very first (Take 1, July 29, 1965) a droning Velvet Underground-like experiment. One hears a number of lyric changes during the “Desolation Row” sessions. For example, early on Dylan sings, near the songs conclusion, “Right now I don’t feel so good,” but by the final take that line has become “Right now I don’t read too good,” which is important in the context of the final four lines: “Right now I don’t read too good, Don’t send me no letters, no, Not unless you mail them, From Desolation Row.”

• Nine takes of “Highway 61 Revisited” were recorded on August 2, 1965. It’s only on Take 7 that the police whistle is tried out, and one can hear Dylan and the others crack up. That novelty effect, as used on the take that made it onto the album (Take 9, August 2, 1965) is crucial to the success of the song, and indicates to me that Dylan understood that he was making rock ‘n’ roll records, which had nothing to do with the folk records of his past.

• Thirty takes of “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” Dylan attempted the song with the Highway 61 Revisited musicians, but wasn’t happy with the outcome, despite a fantastic version (Take 17, July 30, 1965) that was mistakenly released as the A-side of the December 1965 single in place of “Positively 4th Street.” He tries again on November 30, 1965 with his new touring band, The Hawks, and cuts a version he likes (Take 10, November 30, 1965).

Blonde On Blonde

Perhaps his most personal album up to this point, Blonde On Blonde is a surreal novel mostly about male-female relationships gone wrong. I’ve always imagined these songs taking place in Victorian-style homes with sitting rooms, large living rooms and a study, where the characters play out their doomed romances, as narrated in song by an unnamed male character. Yes the music was mostly recorded in Nashville, but there’s a baroque quality. Listen to “Fourth Time Around” or “Just Like a Woman” or “I Want You” or “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.”

As a model/ sometime journalist who observed Dylan and Robbie Robertson working on a song in an Australian hotel room in 1966 told Anthony Scaduto, “…he would say to Robbie: ‘Listen, Robbie, just imagine this cat who is very Elizabethan, with garters and a long shepherd’s horn, and he’s coming over the hill in the morning with the sun rising behind him. That’s the sound I want.’”

No album was so difficult to record for Dylan as Blonde On Blonde. Thirteen sessions with two sets of musicians in two cities – New York and Nashville. The five sessions in New York with all five members of what would become The Band resulted in just two recordings that were released at the time – “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window” (Take 10, November 30, 1965) as a single, and “One of Us Must Know (Sooner Or Later)” (Take 10, November 30, 1965), the only New York track to make it onto the album.

In the fall and winter of 1965, following a controversial show on August 28 in Forest Hills, New York, Dylan and The Hawks hit the road; for Dylan touring was a gruelling experience that continued through the first half of 1966.

For the first Blonde On Blonde session, on October 5, 1965, Dylan didn’t appear to be prepared. Perhaps high on the success of Highway 61 Revisited, “Like A Rolling Stone” and “Positively 4th Street,” or more likely high on the various substances he was using at the time, the only finished song Dylan brought in was “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?” which he had previously attempted with the Highway 61 Revisited band. Take after take was devoted to the so-so “I Wanna Be Your Lover,” which is perhaps a parody of the Stones “I Wanna Be Your Man” (which The Beatles also recorded). There’s a partial take of “Jet Pilot” (Take 1, October 5, 1965) for which Dylan had one verse; the song is notable for being about a transgender five years before The Kinks would release “Lola.” Also recorded were two takes of a verse of “Medicine Sunday” (Take 1, Take 2, October 5, 1965), which would seem to indicate that Dylan hadn’t completed the lyrics.

Nine of The Cutting Edge CDs are devoted to songs recorded during the Blonde On Blonde sessions. A few of the many amazements from those sessions:

• Seventeen takes of Dylan’s post-breakup song, “She’s Your Lover Now,” performed with and without band (in this case the members of The Band). Considered by some to be one of Dylan’s greatest songs, “She’s Your Lover Now” didn’t make the cut. The final version (Take 16, January 21, 1966), an eight minute solo masterpiece with Dylan accompanying himself on what might as well be the whorehouse piano Scott Joplin used, is equal to his genius Basement Tapes recording, “I’m Not There.” A mix of sarcasm, bitterness, humor and regret, the song features fantastic lyrics. At times Dylan is addressing a woman who has left him (or at least the character he is portraying), at other times he is totally dismissive of ex’s new lover. “They both were so glad, To see me destroy everything I had, Pain sure brings out the best in people doesn’t it?… It’s just like a dead man’s last pistol shot, baby… Your mouth used to be so naked, Your eyes used to be so blue, Your hurts used to be so nameless, Your tears used to be so few…” And this to his ex’s current lover: “And you, just what do you do anyway? Ain’t there nothin’ you can say?” And again: “And you, there’s nothing really about you that I can recall.” During the chorus Dylan sings with great sarcasm: “You better do something, She’s your lover now.”

• Eighteen takes of “Visions of Johnana,” some with most of The Hawks, others with the Nashville cats that nailed the recording found on Blonde On Blonde. The song shape-shifts from a full-bore rocker to the ballad that made it onto the record (Take 4, February 14, 1966).

• Two takes of “Medicine Sunday” (Take 1, Take 2, October 5, 1965) recorded with The Hawks, which eventually morphed into “Temporary Like Achilles.” “Well, that midnight train,” Dylan sings over The Hawks ragged but soulful accompaniment, “pulled out all down the track, You’re standing there watching with your hands tied behind your back, And you smile so pretty, and nod to the prison guard, Well, I know you want my loving, mama but you’re so hard.”

• Twenty-four versions of “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later) plus the four separate tracks — one with guitar and organ, one with the vocal, one with piano and drums and one with only guitar and bass – that were mixed to create the version we know and love (Take 24, January 25, 1966).

• Nineteen takes of “Leopard Skin Pill-Box Hat.” Early takes are of a slow 12-bar blues, before Dylan jacks up the tempo. He also tries to turn it into a novelty number (Take 16, February 14, 1966), starting with the ring of a doorbell (the sound courtesy of Al Kooper’s Wurlitzer organ) and some of the studio band answering, “Who’s there?” before Dylan starts in. Another sound effect from Kooper’s Wurlitzer, an automobile horn, becomes so irritating after a few listens that it’s no wonder it wasn’t used on the album version.

And That’s Not All Folks

The final CD contains 21 mostly fantastic hotel room recordings made while Dylan was touring, and includes another of Dylan’s great lost songs, “I Can’t Leave Her Behind.” In Dylan’s unreleased 1966 tour film, “Eat the Document,” we see Dylan and Robbie Robertson in a room at Glasgow’s North British Station Hotel on May 13, 1966 working out the song. That’s the version that ends up, in full, on this CD. Exquisitely beautiful. Also included is the version of Hank Williams’ “Lost Highway” Dylan and Joan Baez are seen singing on May 4, 1965 in his Savoy Hotel room in “Don’t Look Back.” In the film and on this recording Dylan forgets to sing the verse that begins, “I’m a rolling stone…” We hear Dylan’s friend Bob Neuwirth remind him about that verse. Given that Dylan recorded “Like a Rolling Stone” six weeks later, it’s likely that this song is where he got the idea for the chorus/title of his own song.

’Alcatraz to the 9th Power’

The more time I spend with these tracks the deeper I go. Within incomplete takes and complete ones that were not chosen for inclusion on one of the three albums are precious musical and lyrical bits and pieces that I find myself returning to again and again. A particular vocal or guitar riff, a hypnotic rhythm or some cool words Dylan discarded. On several occasions I woke during the night with the riff from “Medicine Sunday” repeating in my head; another night a verse from “She’s Your Lover Now” played in its place. The other morning I got up frantic to hear Dylan and the Highway 61 Revisited band run through take after take of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh…”

It’s as if each song that made it onto an album has all these audio footnotes. And the music aside, there’s pure pleasure in hearing producer Tom Wilson and Dylan banter back and forth before the start of a take, and other studio talk.

“’Alcatraz To The 9th Power,’” Wilson says.

“No!” Dylan yells. “That’s not the name of it.”

“That’s what you told me when you left,” Wilson says.

“I switched songs. This song is, uh, uh, uh, ‘Bank Account Blues,’” Dylan says, followed by a short laugh.

“Heh heh heh heh,” Wilson says. “Correct cue, ‘Bank Account Blues,’ take one, rolling.”

And Dylan sings a beautiful version of “I’ll Keep It With Mine,” accompanying himself on piano.

This Whole 18 CD Set is Crazy, Man

I can’t imagine what younger listeners, those who weren’t around in the mid-‘60s, will make of these 18 CDs – if they do listen. Someone who is 12 years old now, as I was when I first heard “Like a Rolling Stone.” Someone free of the kaleidoscopic times that were changing so fast back then, back 50 years, back when all this went down.

Yeah this is music, but it’s more than music. Just as Dylan was more than music. Just as 1965 and 1966 were more than years, more than time passing. I’m not saying those years were better than any others, what I’m saying is that unique shit went down during those years. Dylan was on fire during those years.

Dylan was in a particular mood each day he went into the studio. The sunlight and moonlight fell on the city a particular way. The news in the papers, and the news that didn’t make the papers was the news of those times. This music came from one man as he lived his very particular life during those years, often amped up on speed, letting his unconscious bleed onto the page, working with producers and musicians who were equally effected by what went down. A year later, perhaps even six months later, everything would have been different.

This whole 18 CD set is crazy, man. It’s so over-the-top, but then again, maybe not. Ralph Waldo Emerson said “moderation in all things,” but I say he’s wrong. Listening to 12 takes of “Desolation Row” may not unravel the mysteries of that song, but it’ll sure take you deep into it. If you listen. And this collection is all about listening. You don’t put it on as background music, you put it on when you want to time trip back to 1965 and 1966 and visit Columbia Studio A in New York and Columbia Music Row Studios in Nashville and the Savoy Hotel in London, when you want to remember events you didn’t experience the first time around, events that become part of your life as you keep listening.

Or maybe what I’m saying is this: you will bring as much to The Cutting Edge as it will bring to you.