By Michael Goldberg.

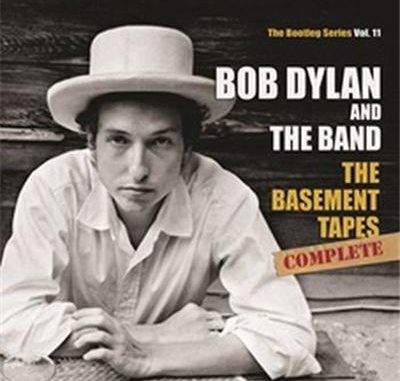

Bob Dylan and The Band

The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series Vol. 11 (Six-CD set) (Columbia Records)

Note: Because the Basement Tapes are, for me, about a time long past, and a place long gone, and the feeling of wonder I still had as a teenager back in 1970 when I first heard some of the Basement songs, I have taken an unconventional approach to this review, mixing fact and fiction, thoughts about the actual music with seemingly unrelated text about young love.

It was time to split the city. The Summer of Love was a bust. They were selling “Love Burgers” on Haight Street. If you’re too young to know, Haight Street in San Francisco was a kind of ground zero for the ‘60s counterculture in 1966. But it wasn’t 1966 anymore, and things had changed. A creepy-crawly vibe would soon turn all the colors black.

***

May of 1970, me and my chick in the back of that Ford pickup with all the camping gear. We’re heading for Big Sur. A bunch of us in five vehicles, maybe six. This was a long time ago. I was 16 and so was Sarah. We make a couple of stops along the way; the last one is to get gas and ‘cause some of us need to use the can. It isn’t a town, isn’t a full block same as you find in a town or a city. It’s some beater houses and a motel and the Texaco. What it is, is a no-name, one of those places you drive through to get from here to there.

Only reason I even get out of that pickup is ‘cause of the Coke machine.

***

The Basement Tapes are a myth. They’re one of those stories that serious music fans, the type of fan that most people would call a collector, and others might call crazy, a nut, get lost in. As the myth has been told and retold since the late ‘60s, Bob Dylan, then one of the greatest, if not the greatest, rock stars in the world, had a motorcycle accident.

After recovering from his accident in the seclusion of an 11-room house in the Byrdcliffe Colony near Woodstock, Dylan called up his band, a handful of musicians who had been known as The Hawks when they backed Canadian rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins, and they joined him, soon renting houses not far from where Dylan was residing, one of which came to be known as Big Pink.

Over the summer, in the basement of Big Pink, they recorded over 100 tracks, including some new Bob Dylan compositions that remain some of his best. When it was all over, Dylan moved on, heading to Nashville to record John Wesley Harding, an album of all new songs, none of which had been recorded in the basement.

As for what eventually became known as the Basement Tapes, acetates were made of 14 songs and sent out to artists with the hopes they’d be covered. The tapes with the rest of the songs were shelved.

Eventually the bootleggers got their hands on those 14 songs, and soon we, the serious, obsessed Dylan fans, heard them too. And as word spread that there were more recordings, many more recordings, we lusted for them the way collectors of ‘78s lust after original pressings of Skip James records, or those of Geeshie Wiley and Elvie Thomas.

And so, for the serious Dylan fan, for us nuts, those tapes became the Holy Grail.

***

It’s one of those ancient curved-corners all-red Vendo Coke machines. The V-81a. Filled with cool-ass bottles of Coke. Warhol’s “Green Coca-Cola Bottles” kinda cool-ass bottles.

Ever seen that Warhol deal? Homage to Duchamp, Warhol’s bottles. Warhol was heavy into Coke. Said Coke symbolized the egalitarian nature of American consumerism. Said it didn’t matter if you were Liz Taylor or a bum, a Coke was a Coke, and no amount of money could get you a better one than the one the bum on the corner was drinking. ‘Course what Warhol didn’t say was Liz Taylor could afford to get her cavities filled. The bum gonna end up with a mouth full of rotten.

I guess that’s what America’s all about. The phony-ass everyone’s equal trip. Authentic real, there’s a hierarchy. Fortune or fame, enough of either can put you up on your high horse, up on the steeple with all the pretty people. Warhol was wrong, Coke tastes a whole lot different if you’re drinking it out on the veranda of some place in Beverly Hills, than in the fucking gutter.

***

On July 29, 1966, Bob Dylan, who as a kid idolized James Dean, had an accident while riding a 500cc Triumph Tiger 100 motorcycle on a road near his manager’s house in West Sugerties, not far from Woodstock, New York. Dylan was on break from a grueling world tour during which fans of his folk music booed his new rock ‘n’ roll sound. One of ‘em called him Judas.

“I was on the road for almost five years,” Dylan told Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner during a 1969 interview, looking back to that fateful day, the day of the motorcycle accident. “It wore me down. I was on drugs, a lot of things. A lot of things just to keep going, you know? And I don’t want to live that way anymore. And uh… I’m just waiting for a better time – you know what I mean?

Wenner asks a follow-up question.

“Well,” Dylan says. “I’d like to slow down the pace a little.”

Dylan did slow the pace. “I thought that I was just gonna get up and go back to doing what I was doing before…,” Dylan told Wenner. “But I couldn’t do it anymore.”

Dylan’s crazy schedule of touring and recording – he cut three of the best rock albums ever made, in 15 months! – was over. Instead he holed up with his family at the Byrdcliffe house, known as Hi Lo Ha, having replaced hectic New York with a pastoral scene. Working with filmmaker Howard Alk, Dylan completed a documentary, Eat The Document, using footage D. A. Pennebaker shot of the 1966 tour. The film was commissioned for the ABC television series Stage ’66, but was rejected by ABC and has never been officially released, although a bootleg version circulates, and periodically shows up online.

Still in upstate New York, at some point in early 1967 Dylan and some members of The Hawks began a series of informal music sessions in what was referred to as the “Red Room,” a sitting room at Hi Lo Ha that was no longer painted red, if ever it was. The music they made was recorded on a reel-to-reel tape recorder – one that took seven inch reels of quarter-inch tape — by Garth Hudson, one of the musicians who was also participating in the sessions along with Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko and Richard Manuel. Later they would be joined by Levon Helm.

The genesis of the sessions may have been pressure Albert Grossman exerted on Dylan to come up with more songs, songs for other artists to cover. Grossman owned half of Dylan’s publishing, so it was in Grossman’s financial interest to get more songs out of Dylan while he was still a big star.

Dylan told Jann Wenner, “No, they weren’t demos for myself, they were demos of the songs. I was being PUSHED again … into coming up with some songs. You know how those things go.”

Still, whatever the outside pressure, what happened when the tape was rolling was enjoyable, both for the musicians and for Dylan.

“The Basement Tapes refers to the basement there at Big Pink, obviously, but it also refers to a process, a homemade process,” Robbie Robertson was quoted as saying in Sid Griffin’s book about the Basement Tapes, “Million Dollar Bash.” That quote also appears in the liner notes Griffin wrote for The Basement Tapes Complete: The Bootleg Series Vol. 11, the 6-CD set was released on November 4, 2014.

“So some things we recorded at Bob’s house, some things we recorded at Rick’s house…we were here and there, so what it really means is ‘homemade’ as opposed to a single location in a formal studio.”

Talking about the sessions to Jann Wenner, Dylan said just moments after he spoke of being “PUSHED” to demo new songs, “They were just fun to do. That’s all. They were a kick to do. Fact, I’d do it all again. You know, that’s really the way to do a recording—in a peaceful, relaxed setting—in somebody’s basement. With the windows open … and a dog lying on the floor.”

***

After I check out the V-81a I call to her, “Sarah, a time machine.”

She climbs out of that pickup and runs over. We were both into old stuff – rusted signs, dusty felt hats, second-hand clothes. For sure she digs that Coke machine, and the Warhol green bottles we can see through the glass in the door, and I don’t have to say nothing more, me and Sarah tuned to the same station. She turns and leans back against the V-81a, her grey-blue eyes filled with me.

I know she wants one. Fifteen cents. That’s what a Coke cost back then. I buy two bottles, one for me, one for her. Before we split outta there, her still leaning against the V-81a, I get my arms around her, give her a kiss, her mouth so sweet, sweeter than any Coke.

***

Before the motorcycle accident, before Dylan really settled into the house in Byrdcliffe, back a few years to 1965 and 1966, he was someone else. A rock star. Hard and wiry, wearing a rock ‘n’ roll leather jacket or a mod houndstooth checked suit, black Beatle boots, sometimes pop art polka dot shirts, his hair frizzing high off his head, and always the shades. He played a real rock ‘n’ roll guitar, a Fender Stratocaster, just like another of his idols, the late Buddy Holly.

His songs, too, the ones on side one of Bringing It All Back Home and all of Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde were loud, raucous urban rock ‘n’ roll. During the 1966 tour everything was amped up with speed. Take a fork and jam it into an electric outlet. That was the music Dylan made in ’65 and ‘66.

The Dylan who eventually surfaced in Woodstock, who let Elliott Landy take a bunch of amazing photos, one of which was famously on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, appeared to be a different person. His hair cut short, Dylan let Landy photograph him in a seersucker sport coat, a white shirt and beige slacks. It’s obvious from the photos that he’s put on a bit of weight. At times he grew a short beard and wore a flat-brimmed hat.

Who was this country preacher who was still going by the name Bob Dylan?

And what kind of music would he make?

***

I could waste time filling you in on us getting to Julia Pfeiffer State Park in Big Sur, and setting up tents and all of it, but the reason I’m telling you about me and Sarah going to Big Sur is ‘cause of one thing, so that’s what I’m gonna tell.

Our friends had crashed out in their tents, and we were in ours too, lying next to each other, me hoping she’d let me touch her, and we’d make-out, only that’s not what happened.

“Want to get naked?” she says. “Under the stars?”

Oh man, that was so Sarah, pop out with some crazy deal I’d never think of in a million years.

“Well I’m doing it,” she says. “You coming?”

***

The music Bob Dylan and his band recorded that summer wasn’t like anything we’d heard from Dylan before. Sure Robbie was playing his Telecaster at times, and Garth was often at his organ, but what they created was a brand new sound that could have come from a 100 years earlier — even the rock ‘n’ roll sounded like something you’d stumble across in a shack of a bar in the Appalachians.

At some point the recordings became known as the Basement Tapes.

I’ve been hearing bits and pieces since I was 17. They first showed up on a bootleg, Great White Wonder. I bought that one in 1970 and I still have it, a two-album set with Great White Wonder stamped in purple ink in the upper right corner. There’s no other writing on the cover or inside. The round white labels on the discs themselves are blank. In 1970 you had know what this was; just to own Great White Wonder made you an insider.

Among the 25 then-rare Dylan recordings on the two discs were seven from the Basement Tapes sessions, and among those seven were five songs right up with the best Dylan had officially released: “I Shall Be Released,” “Too Much of Nothing,” Nothing Was Delivered,” “Tears of Rage” and “This Wheel’s On Fire.” Years later I learned that those were simply highlights of a massive treasure trove.

Now we have that treasure trove, 139 tracks (one is a hidden track at the end of the sixth CD) recorded during that infamous summer of ‘67, the same summer The Beatles released their grandiose Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Where to begin?

More than six and a half hours of music, from the sublime (“I’m Not There,” “Wild Wolf,” “Edge Of The Ocean”) to the ridiculous (“See You Later, Allen Ginsberg,” take one of “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere”) from overheated rockabilly (“Odds & Ends,” “Dress It Up, Better have It All”) to melancholy ballads (“The French Girl,” “Ol’ Roison the Beau,” “900 Miles From My Home”).

The sessions were never intended to produce an album. Recording was low-key compared to working in a traditional studio with the clock ticking. But for the musicians it couldn’t have been that low-key. They were on salary, working for Mr. Dylan, and he had something in mind. As crazy as some of the recordings are (Robbie Robertson described some of the sessions as “reefer run amok”), it’s all on Dylan’s terms. If Dylan wants to sing an absurd song such as ‘Lo And Behold,” that’s what happens, and if he wants to get serious and record “Sign On The Cross,” well what are you waiting for, boys?

At some point, after dozens of songs had been recorded, after Dylan had written a slew of masterpieces, some of which would become standards (“I Shall Be Released”), Garth Hudson was asked, probably by Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman, to put together a reel of the best of what Dylan had written. And so 14 songs ended up being sent out in hopes other artists would cover them. Not to worry, they did.

“They were just songs we had done for the publishing company,” Dylan told Kurt Loder in 1984, nearly two decades and a million lifetimes later. “For other artists to record those songs. I wouldn’t have put them out.”

I don’t believe that. Whatever Dylan’s initial intention, as the great new songs piled up, Dylan must have known he was on to something. His comments to Loder are the kinda thing Dylan says in an interview, the public Dylan, the Dylan that once in a blue moon talks to the press. Dylan being Dylan.

But anyway.

As I’ve been listening to the six CDs, listened in some cases to songs that were also on bootleg Basement Tapescollections I bought in the past, I began to think about what it is that makes me keep coming back to these and other Dylan recordings.

Certainly it starts with Dylan’s voice, and the way he sings a word, or a phrase. No one sings like Bob Dylan, and in the ‘60s he was certainly at the top of his game.

For example, in the song “I’m Not There,’ Dylan sings a couple verses and then his voice rises and there’s an ache in his voice that just slays me as he sings:

“I believe where she’d stop him if she wants time to care

I believe that she’d look upon the side him to care

And I’d go by the Lord and when she’s on my way

But I don’t belong there.”

In his book, Down The Highway: The Life Of Bob Dylan, Howard Sounes quotes Robbie Robertson talking about how Dylan would bring in folk songs to teach the musicians, who knew almost nothing about folk or country music.

“I didn’t care that much for what he was turning me on to,” Robertson said. “[But] when he sang those songs I liked them a lot. And I couldn’t tell which were the songs that he wrote, and which were the songs somebody else wrote. For instance, when we were in the basement, and he would sing all these songs, I didn’t know whether he wrote ‘Royal Canal’ or whether it was an old folk song. And [it]was an extraordinary education to be connected to all of this great music. A lot of it came from the British Isles and from the mountains of America and down those mountains and into the cities.”

Listen to the Basement songs and you hear what Robertson heard, and understand why he enthuses in that way about Dylan’s singing.

But it’s not only the singing that makes these recordings so special. The melodies too. I love Dylan’s melodies, and how he plays the guitar. And the music the other guys make. And of course the words, always the words.

Put it all together and it adds up to so much more than the sum of the parts. Put it all together and it often forms a huge question mark. There is mystery in the music Bob Dylan made that summer. So many of the originals are like transcriptions of dreams, only transcripts for which the “cut-up” technique Burroughs borrowed from the Dadaists has been applied.

Dylan’s best songs are not the straightforward protest songs from the early ‘60s – “Masters Of War” or “The Times They Are A-Changing.” Rather, it’s songs like “Visions Of Johanna,” songs that are opaque. Songs whose meaning defies understanding. Those are the great ones. I’ve listened to “Visions Of Johanna” 100s of times and still its mysteries remain intact.

And a song such as “I’m Not There” – do you know what it’s about?

At the Big Pink house, Dylan would be upstairs writing, and when a song was finished he’d come down to the basement (actually a garage turned into a clubhouse/ studio) and they’d record it. Revisions and arrangements weren’t always done on the fly. According to Sounes, Dylan would ask Hudson for copies of songs he wanted to work on. Still, it sounds like a lot of what we get here came straight from Dylan’s brain onto the page and then, as Dylan sang and he and the band played, was captured on two-track quarter-inch tape.

The lyrics to many of Dylan’s Basement songs are opaque too; as if they’re written in an invisible ink, or in a language that defies translation. And it’s that mystery that keeps bringing me back. One line stands out, gives up something one day, then pulls it back on another.

I mean what does this mean:

“Nothing was delivered

And I tell this truth to you,

Not out of spite or anger

But simply because it’s true

Now, I hope you won’t object to this,

Giving back all of what you owe,

The fewer words you have to waste on this,

The sooner you can go

Nothing is better, nothing is best,

Take heed of this and get plenty of rest.”

Or this:

If your mem’ry serves you well,

We were goin’ to meet again and wait,

So I’m goin’ to unpack all my things

And sit before it gets too late.

No man alive will come to you

With another tale to tell,

But you know that we shall meet again

If your mem’ry serves you well.”

You try and try to figure it out, what Dylan is saying, and then you give up for a while and just dig the sound, and leave it for another day to try and try again.

Those are both incredible songs. We’ve heard them covered for decades now, and we’ve heard sub-quality bootleg versions. Now we get to hear them right off the tape they were originally recorded to, with the benefit of Garth Hudson and expert sound engineers, who did their best to get them to sound the way Hudson originally heard the music in the basement. And there are other Dylan originals here – songs you haven’t heart before such as “Wild Wolf” and “Edge Of the Ocean” that are just as good.

And the covers. So many songs that Dylan makes his own.

Five songs into the set we get Johnny Cash’s ‘50s recording, “Belshazzar” (“a religious kind of a song,” Cash called it), only where Cash did the song in what was typical Johnny Cash style, very straightforward and country with his “Folsom Prison Blues” guitar ticking through it, Dylan gives us an Okie rocker. Anchored by Hudson’s swirling organ and driving electric guitar from Robertson, Dylan’s version is all hocus pocus. But what makes this one such a keeper are the ragged male harmony vocals of Dylan and some of the Hawks as they sing the chorus:

“For he was weighed in the balance and found wanting

His kingdom was divided, couldn’t stand

He was weighed in the balance and found wanting

His houses were built upon the sand.”

There are also terrific versions of Johnny Cash’s “Big River,” “Folsom Prison Blues” and “Still In Town”; Hank William’s “You Win Again”; The Fleetwoods’ “Mr. Blue”; Red Souvine’s “Waltzing With Sin” and I could on.

Remember, we’re talking about 139 tracks. Sure some are, in some cases, multiple takes of the same song, but still. Even taking that into consideration, there’s probably 100 different songs here.

Where to begin?

***

We’re barefoot, carry our sleeping bags away from the tents, using the moonlight to make our way right to the edge of the cliff. Man, I could hear that huge-ass ocean, dark and wild, far below us. I turn on the flashlight and we find a flat spot where there aren’t too many rocks. Nothing worse then lying on a fucking rock. We get the bags down, one next to the other, and that’s when Sarah starts to strip.

***

You can get seriously deep into this music. Greil Marcus wrote an entire book about these recordings. He called it The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes. And Sid Griffin wrote a book about them too, Million Dollar Bash.

But you don’t have to read a book to appreciate this music. All you need are the CDs and plenty of time. When I first got a four-CD bootleg of most but not all of the music, it was too much for me. I was impatient. I listened, but I didn’t really listen. And then the CDs sat on the shelf for a few years. But I came back to them and spent more time listening. And as I kept listening more songs kept emerging as my favorites.

One week it was Ian Tyson’s “The French Girl,” a heartbreaking ballad about a chance encounter. For a month or more I was obsessed with “I’m Not There,” which for a while I thought was the best song recorded that summer. More time, more listening. And then one day it was the country covers by Johnny Cash and Hank Williams and others that made my day.

What I’m trying to tell you is you really need to invest some serious time. Sure there are some throwaways – Bobby Bare’s “All American Boy” for instance – but for me much of this set, most of it, is really good.

And the more you listen, the more that will be revealed.

***

It’s a quarter moon, but the sky clear and the air pure and the smell of the salt water. We’re at the edge of the planet, and I’m so alive.

There in the moonlight she undoes a strap of her overalls.. She’s got the other strap over her left shoulder, doesn’t even undo that one, pulls her overalls down and steps out of ‘em. Her legs pale, and I wanna touch ‘em, I want to rub my face against her thighs, but instead I undo my belt. She’s unbuttoning her blouse, gets it off, folds it careful and puts it inside her sleeping bag and her overalls too and I get my jeans off, and I stop. Oh man, nothing in the known world could stop my eyes from looking and looking and looking some more. First time I see her naked. Her breasts smooth and firm and dusted with sex dust. She pulls her hair out of her face, her nipples aimed right at me.

“God, Sarah.”

Back then I’m on the fence about God. Don’t know yet there isn’t a God. It wasn’t until everything was a ruin I figured it out.

She’s looking up at the sky. “What is it?” she says. “The stars?”

“Yeah,” I say. “The stars. Both of them.”

“Which stars?” she says.

“Don’t be silly,” I say. “Never seen anything — person or flower, tree or animal, mountain or ocean — crazy-wild beautiful as you, Sarah.”

Hearing me she doesn’t try not to smile ‘cause she knows I believe every word of it and she believes those words too, she believes I love her then, and will love her forever. It’s in the way those bigger blue eyes look at me. That’s the deal about when you’re still young and you got nothing for comparison. You can think something’s gonna go on and on forever. It’s only later I know how much I had, and how much I lost.

Michael Goldberg has recently published his rock ‘n’ roll novel,True Love Scars. It is available in Kindle and paperback at Amazon here:True Love Scars.