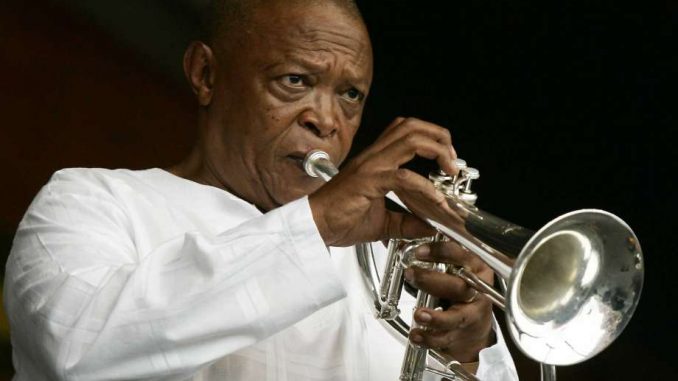

The death of legendary South African musician Hugh Masekela at 78 on Tuesday January 23rd, following a decade-long battle with cancer, has delivered a mortal blow to South African jazz and to the humanitarian and arts scenes in that country in general.

Widely known as the “Father of South African jazz”, the trumpeter, singer and composer pioneered the genre in 1950s’ Johannesburg as a pivotal member of the highly influential Jazz Epistles.

This scribe had the pleasure of interviewing Masekela long-distance back in 2009, then catching up with him face-to-face backstage at the Bellingen Global Carnival, where my band Kamerunga also happened to be performing. He actually agreed to jam with Kamerunga on a township jive influenced piece of ours (‘Afreels’) before realising that a gig in Sydney beckoned. Oh what might have been!

Forty-five minutes on the phone to him at his Jo’burg home was barely time enough to cover the projects he was juggling at that time, let alone his accomplishments in more than half-a-century at the top of the music tree or his achievements as a social and cultural warrior and his relationships with the likes of Nelson Mandela, Paul Simon, Fela Kuti, Bob Marley and many other legendary people. The trumpeting lion of South Africa might have turned seventy earlier that year, but there were scant signs of him slowing down.

During thirty years in exile, the flugelhorn maestro and his first wife, the diva Miriam Makeba, were voices abroad for their oppressed brothers and sisters back home. They helped bring an awareness of the iniquitous apartheid doctrine to the rest of the world. Masekela campaigned against conflict and social injustice and attempted to right the wrongs of South African society up to his death.

As a teenager, Masekela was mentored by master musicians and he’s always went out of his way to assist young players himself, giving a platform to a fresh generation of South African talent with his own record label Chisa Entertainment.

Co-founder of the Botswana International School of Music in the early ‘eighties, he subsequently set up an academy in his hometown, Johannesburg. “Outstanding young artists from the entire African diaspora will be able to come and learn those skills that they don’t have,” he enthused during our 2009 telephone hook-up.

Coincidentally, another famous South African jazz musician and exile, Abdullah Ibrahim, founded a similar establishment in Cape Town. Masekela and Ibrahim [aka Dollar Brand] were bandmates back in the late 1950s, in the aforementioned Jazz Epistles. “We did the first long-playing record here by a group,” the trumpeter told me. “We broke all attendance records in South Africa. We were booked to go on a major national tour when the Sharpville Massacre happened and gatherings of more than ten people were banned.” Sadly, The Epistles were forced to disband in their prime. “We would have gone far,” Masekela declared. “We lived and breathed music. We rehearsed all day and played all night, and we only rested to change and eat. It was a very dynamic band.”

Masekela managed to get a passport in 1960 and, with assistance from Harry Belafonte, fled a fast deteriorating situation in South Africa for New York. There he was befriended by some of the giants of the local be bop scene. “Miriam Makeba introduced me to Dizzy Gillespie and he adopted me; he was sort of like a foster father,” he told me. “Whenever he was playing at a club in New York I’d sit in with him. He was a most wonderful person. He was extremely generous. He introduced me to all the musicians, including Miles Davis.”

During his stay in the States, Masekela got to catch up with another of his heroes, Louis Armstrong, who had sent a 17-year-old Hugh one of his own trumpets several years earlier. “I had the privilege and joy to meet him a few times and he actually was one of the most humble people I’ve ever met,” the trumpeter related. “He never finished a paragraph without mentioning New Orleans. He said: ‘If you forget where you’ve come from, you’re doomed’. I never forgot that. I think more than the instrument he gave me, that was the one of the greatest gifts and pieces of advice I ever got.” Satchmo’s trumpet is now in the National Museum of South Africa: “They borrowed it for six months and they kept expanding that period. It’s safer with them than with me,” he laughed.

The trumpet that got Masekela going was given to him by anti-apartheid activist and Anglican priest Trevor Huddleston, and he later played in the Huddleston Jazz Band, South Africa’s first youth orchestra.

Back in 2009 when I spoke to him, Masekela was about to finish his second novel. “The first one was a township thriller, this one is a love story, but they’re both about contemporary times. The thriller is about a musician who’s just come back from abroad and is doing very well and then he’s framed for a murder that he didn’t commit, and he has to exonerate himself.”

Masekela was no stranger to musicals. As a young man, he played in King Kong, which enjoyed record-breaking runs both at home and on London’s West End. “It was the first South African musical,” he proudly told me. “It played to the whole country for a year. It was a major hit and launched Miriam Makeba’s international interests and gave me and many people a chance to try their talent abroad. For myself and the other musicians in the show it was a great privilege because it was the first time that we had earned that much money per week. We got twenty pounds a week for a year, which was a ridiculous amount of money for teenagers at that time. We got to see our own country from a very high level in terms of accommodation and travel. It was a fabulous experience.”

Three decades later, Masekela co-wrote the musical Sarafina! “It turned out to be much bigger than King Kong because it played Broadway for two years and toured Europe and the States. It also became a film, starring Whoopi Goldberg.”

Masekela penned Sarafina! — based on the Soweto Riots — after leaving Botswana, where his outspoken political stance made him a potential target for South African death squads, for London. It was during his stay in Botswana that he wrote his most famous song, ‘Bring Him Back Home’, which has become an anthem for Nelson Mandela.

“It was never intended that way,” its creator insisted. “When I turned forty-six, Mandela sent me a birthday letter, smuggled out of prison and delivered to me in Botswana. He knew the names of my children, my wife, everything I was doing. He was wishing me strength and success and I was just blown away that somebody who had been in jail for over twenty years could send such an inspirational message. So I just went to the piano and started singing it [the message]. My wife came in and said, ‘I don’t know that song — when did you write it’, and I said: ‘I didn’t write it; Mandela just sent it!’ When we recorded it, I didn’t expect it to become what it did.”

Masekela finally returned to South Africa in 1990, following Mandela’s release, and embarked on his first tour of the country. His shows sold out in the major cities, and his subsequent albums, Black to the Future and Sixty, were both massive hits.

The ‘nineties also saw him tour the world for three years as MD with Paul Simon’s Graceland. “I knew Paul from twenty years before he recorded that album because we had the same producer, Tom Wilson, who also produced Bob Dylan in the sixties. We remained friends. After he had done Graceland, he called me in London, where I was living, and said: ‘I’ve just done this album in South Africa and I wanna play it for you’. When I heard it, I was blown away. He said: ‘If it becomes a success would you join me on a tour’. He added: ‘I don’t know how I’m gonna do it because I recorded it with over a hundred musicians.’ I said: ‘I think what you should do is get Miriam Makeba to come and do it with us, and Ladysmith Black Mambazo, and we integrated that into it. Many of the people who brought that album had never heard South African music before so it was a great catalyst. It was a wonderful tour. Paul Simon is a very generous and very gentle person.”

Hugh Masekela and Paul Simon also worked together on a benefit gig for the South African AIDS Foundation, of which the septuagenarian was a staunch supporter.

Masekela also enjoyed fruitful liaisons with Afrobeat creator Fela Kuti and reggae legend Bob Marley. “Fela opened West Africa to me. He invited me to come and stay with him in Lagos. I stayed with him for a month in 1972. I’d had enough of the States by that time. He invited me to become a guest performer in his band, and took me on a West African tour.”

Masekela and Kuti remained close friends until Fela’s death. “We were very close because we had the common bond of being thorns in the side of injustice. He was also one of the funniest people that I ever met. We laughed so much. In fact, our relationship was based mostly on laughter.

The association with Bob Marley, he revealed, came up about through his friendship with Johnny Nash. “Johnny went to live in Jamaica for quite a while, and I used to visit him there and that’s when he was nurturing his reggae thing. He was the first to break out reggae with ‘Stir It Up’, which was a Bob Marley song, and then he did ‘I Can See Clearly’. He introduced me to Bob, who must have been about fifteen or sixteen then. I played on one of his first albums, on I think about four songs. We remained friends after that. We were very heartbroken when he got sick. I once did a cover of ‘No Woman, No Cry’ in the late eighties — I changed the lyrics to refer to the South African situation at the time.”

By Tony Hillier