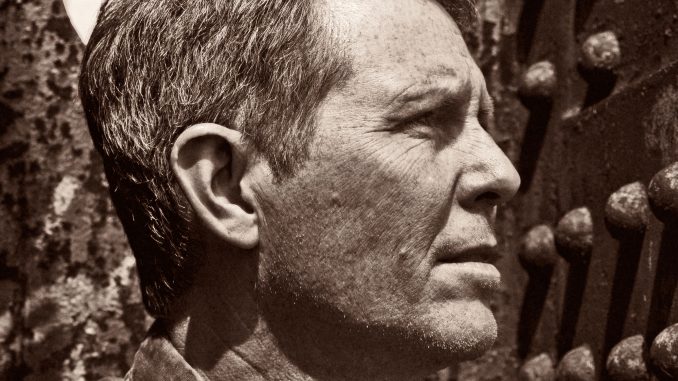

American country artist Robbie Fulks is huge in small circles here in Australia. Active since the late 80s as a singer, guitarist and writer, he’s the author of insurgent country classics, heart-stopping ballads, honky tonk masterpieces and more recently, the best old timey tunes an old-timer never wrote.

Robbie has been nominated for two Grammys this year; his beautiful album, Upland Stories (Bloodshot, Steve Albini) is up for Best Folk Album and single Alabama At Night, Best American Roots Song.

After meeting in Nashville last September, Robbie and I spoke via email recently.

I have always loved the range of your vocal approaches to different songs; listening to earlier work such as that on 13 Hillbilly Giants from 2000 reminds me of what a supple and ‘classic’ country voice you have. Then there are the many character and comedic parts you’ve played ( viz. Countrier Than Thou, Fuck This Town, We’re On The Road, I Wanna Be Mama’ed ) , the smooth countrypolitan stylings to be found on Georgia Hard, as well as the high-energy hollering that goes on occasionally. The last two albums you’ve made have an intimacy which I haven’t really heard you employ in the past. I’m wondering if this signifies an acceptance of a ‘true’ sound, the real Robbie if you will, and whether you’ve come to enjoy your own voice more over time, with less need for the tricks we use when younger?

I became aware that my voice annoyed some people after the first couple records. Mostly I got compliments on my singing but then when parties not inclined to be friendly, or maybe outside the bluegrass/country continuum, commented on or reviewed my records, sometimes they’d refer to the gratingly nasal singing…so to me any tricks are more a thing of now than then – e.g. I have a sort of husky vocal persona that I use now for a lot of ballad singing. It feels, at this point anyway, too natural for me to call it a trick; I don’t think about it anymore. And the intimacy – as I’ve made more records I’ve better understood how to relate to the microphone, how to judge what I’m hearing in a headset, etc. Mainly just projecting at 1/4 the intensity that I naturally feel like.

I attended a talk about Woody Guthrie at Americana which I loved, a panel of various experts discussing his relevance in today’s world ( the ol’ no-brainer, I would have said ) and one of the panellists described Woody as a ‘compulsive communicator’. I immediately identified with that idea and believe that apart from my love of showing off and clowning etc., my fundamental urge is to connect and share ideas and thoughts with others. I’m always listening out for the word, phrase, rhyme I feel I could easily have written myself and love the feeling of getting what someone else has written. Do you see yourself as a communicator, a conduit, a creator or all of the above?

I guess I see myself as making a ball that gets thrown out and then, if all goes as planned, returned. The ball itself, the song, isn’t of any use and in a way is only a potential object until the game is on.

I was thinking about my crippling need to resolve dilemmas in my songwriting. When I resist this temptation, the result is always better. Have you thought about this and how do you know when a story needs a resolution and when it doesn’t?

In my view there needs to be planted a perception toward the end of the song, no matter how gently, that we’ve gone from A to B, and that B is, if not some kind of a clear endpoint, then at least a logical place to close. That seems to me a bare minimum of what your job entails in making a story. In orally transmitted sets of lyrics this doesn’t often hold, and so a song like “Black Eyed Susie,” in which “all I need to make me happy is two little boys to call me Pappy” has no linear connection to “black-eyed Susie went huckleberry picking,” is hard to memorize in a definite train of verses. But if you’re writing a song of that nature, as opposed to learning one that already exists, then I think that, even then, the A-to-B idea comes into play. Writing comes with a set of formal (if very flexible) rules while passing by ear across time and generations doesn’t, and the two methods lead to different results. Opposite Black-Eyed Susie on the spectrum of gentle-to-definite lyrical resolutions might be a modern country ballad with an attached lesson, where some life situation leads inexorably to a realization about humanity or God or justice or a better way to live….

What other musical adventures does your wife Donna take part in? I love her vocal work on your albums, and her very distinctive full-throated sound.

She makes up great ditties around the house. “I’m Not Talking To You” is one of my favorites. She’s a good actress and did some musicals years and years ago, but she doesn’t do much theatrically anymore, and even less musically. Voiceover is her thing.

You’re prolific, yet I wouldn’t call any of your albums ill-considered or rushed. Do you set aside a certain amount of time every week/month/year to record, or is it more haphazard than that?

I work on new music most Tuesdays in studio these days, which compels a level of productivity. The stuff that ends up on released records is a small-ish subset of what I record and a much smaller subset yet of what I write – that’s the main quality control I use – surplus supply and lots of throwing away.

I find your ballads absolutely devastating – the best example of this I’ve heard recently is I Just Want To Meet The Man which I found on the Very Best Of, an excellent and fascinating compendium. There’s always a wry aspect, but my heart is shaken every time I hear your anguished, enraged roar at the end of that song. It’s not easy for most of us to move subtly between moods and points of view in songwriting and performance, but this is a masterclass in building emotion with twists resulting in a completely believable climax.

Thanks…I was into that “Carrie” sort of ending for Meet the Man back then, but now I just make my voice low and deadly serious and kind of soft…

We know you spent time as a songwriter in Nashville. Were you writing only for other people at that time and hoping for a break as a performer too? Was there a particular incident that precipitated the end of that work or more of a cumulative realisation?

It was a 3-year contract and I just worked through it. At the end I was phoning it in because I could see nothing was coming of it, but for the first half or so of the term I was banging them out fast and furious. I wanted into the business of music in any way possible. In 1993 I was just getting into songwriting for country artists via the publisher, and at the same time I was starting to make my offbrand personal take on country music as an artist for Bloodshot, and though I didn’t really want to be stuck long in either of those boxes, I thought one of them might help propel me onto the next level. It turned out to be my own records, but I loved trying to get the hang of commercial writing, bulk writing, co-writing, all good things to immerse in and strengthen your craft. And I just like to stay busy too.

I just adore your onstage relationship with the other Robbie ( Gjersoe, dobro, guitar and vocals ) . You are perfect foils for each other physically and musically and so obviously love and enjoy each other. Tell me about you and him, would ya?

Thanks, he’d like hearing that. When we met, in our late 20s, we found that we shared the same offbeat tastes in what you might call unpopular popular music. In rock we were into T-Bone Burnett and NRBQ records, for instance. Outside of rock, he was more deeply into jazz and I into country and bluegrass, so we helped fill in one another’s gaps most likely, but even so he was well-informed on Doc Watson and Hank Williams and I was moderately up on Django and Blossom Dearie. So we had a double-persona thing going at the outset, and now, 27 years later, we’re able to anticipate and complete each others’ musical thoughts when we play – it seems to be what naturally happens when you play with someone for years on end.

You’ve cited singers such as George Jones and guitarists like Don Rich as influences on your singing and playing. As a songwriter, who floats your boat? Can you recall the first song you heard that melted your mind? And what effect has reading poetry and/or literature had on your craft?

Too many to name but to name a few: Harlan Howard, Roger Miller, Dennis Linde, Bob McDill, Bobby Charles, Arthur Alexander, Mickey Newbury, Lieber/Stoller, Doc Pomus, Stephen Sondheim, Nick Lowe, Otis Blackwell, Felice/Boudleaux Bryant, John D Loudermilk, Dan Penn, Dallas Frazier, Freddy Powers, Lucinda Williams, Norman Blake. Some of the first songs to melt my mind were those grisly folk songs. “SchoolHouse Fire” by Country Gentlemen, “Down With The Old Canoe” by the Dixon Bros., “Didn’t Hear Nobody Pray” by Roy Acuff, “Omie Wise” by Doc Watson…those songs were awful for a 5-year-old to hear! I think those death ballads must have directed me into a love of horror movies and other morbidities that’s become a permanent part of my aesthetic. Poetry I don’t really read much, except for Emily Dickinson, I pick up a little book of hers pretty regularly. Literature influences my song lyrics often rather awkwardly. I tend to work too cerebrally, too in the mode of lush metaphor and grandiose ambiguities, in my first drafts, and then most of my editing in later drafts is getting it simpler and trying to figure out what the hell I was getting at in the first place.

I’ve found the variety of styles on your albums dazzling. The way they hang together is amazing. Is there a conscious process to this assembly or choice of tunes or do they arrive in batches and seem to work together in a natural way?

Thank you, Sarah. It’s extremely conscious. Putting together albums I puzzle a lot over how broad the range should be, what’s the right orchestration, what song will go first and what last, etc. For most of my records I start with an idea of what I want to do. With Georgia Hard, a 1970s-influenced C&W album; with Couples in Trouble, a genre-defying lyric/story-prominent album; with Gone Away Backward, a bleak small-group old-school acoustic country album merging themes of contemporary USA and the mental life of a middle-aged guy. When about half the songs are in place, then the range and orchestration start really coming into focus. But even then, it’s not altogether known what I’ve got until it’s ready to go to mastering. A steady uncovering.

How do you care for your hands to keep them flying around the fretboard? Have you noticed any change to the way touring/recording affects you physically? I ask this because I’ve noticed an awareness of age in the songs you’ve published most recently; references to illness, infirmity, weakness, and wondering if that’s a fear you have or just a foreshadowing of the future?

Hm, I would say that death and illness feel fruitful to write about since they’re universal, and if I’m writing more about them now (though I’m not sure that’s so) then perhaps it’s because not being able to write so much about romance and sex, which would be a little disgusting at my age, opens a vacancy.

Nothing for my hands, so far they just seem to work on their own. Touring is no big deal, especially if I can keep on top of exercise and forego the 4th drink at the end of the night.

Is it true that you’re frightened of Australia’s poisonous spiders and snakes, sharks and aggressive kangaroos? We’re all wondering why else you might not have made your way south as yet…

I am frightened of frightening animals, true, but I’d come down there if I got a good enough offer, in a heartbeat.

Finally, are you going to take up banjo once again, despite Aunt Peg’s admonition to put it down? Is that you playing it on America’s A Hard Religion? ( That and I Should Have Never Come Home are my 2 favourite songs at the moment from Upland Stories.)

I play it all the time! And yes that’s me on America (and on Aunt Peg). She wasn’t as mean to me as I make out, she just didn’t kiss my ass. And she said “throw those picks away if you want to play like me,” which I definitely did not. I don’t care what anybody says about banjo music, I love it!