Reviewed by Bernard Zuel.

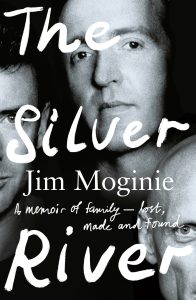

JIM MOGINIE

The Silver River (Harper Collins)

There are many things in this book, by Midnight Oil’s founding member/songwriter/guitarist, could be called, but one that does not and never was intended to apply is a comprehensive history of Midnight Oil.

There are many things in this book, by Midnight Oil’s founding member/songwriter/guitarist, could be called, but one that does not and never was intended to apply is a comprehensive history of Midnight Oil.

You want facts? You want figures? You want details? Forgedaboutit (well except for the specs on a lot of the gear he’s used over the years, which will satisfy tech nerds). Whole albums are mentioned only in passing, several major tours and shows are ignored or offered as afterthoughts, the intricacies of songwriting come in and out of focus, the critical and commercial responses throughout the career rate mentions but are not fully examined – Moginie, possibly bored of that detail, having lived it, figures you can get that somewhere else, along with your stats – and the relationships within the band are assayed lightly, at most in inference.

It’s not just that internal gossip and external judgement are avoided in the same way there’s not any serious whiff of bad behaviour – because frankly how could it be otherwise? Firstly, this is a band that never really indulged themselves in excess. Sensible, solid middle-class boys from sensible solid middle-class families who attended sensible solid middle-class private schools and sensible solid sandstone universities doing sensible solid degrees like science and law, they drank, they smoked dope, they played loudly, but didn’t see the point or satisfaction of trashing rooms, reputations or themselves.

None of them, and certainly not Moginie – who wasn’t as publicly silent as fellow guitarist/songwriter Martin Rotsey or their principal bassplayers, Andrew “Bear” James, Peter “Giffo” Gifford and Bones Hillman, but was well short of the voluble drummer/songwriter Rob Hirst and singer/songwriter Peter Garrett – ever spilled secrets during the band’s long existence or in their own memoirs (in the case of Hirst and Garrett), and that isn’t going to change now.

Maybe we have to accept that they really did like each other enough and respect each other enough not to, beyond a vague “some people” didn’t like this or that. And maybe we have to read between the lines when it comes to things like the mad genius/sometimes blustering boorishness of their longtime manager Gary Morris, and the role religion played in and around Morris and some band members.

What The Silver River is is a poetic and beautifully written at times personal story about a man who probably wasn’t made for this job, though he loved it beyond reason, a man who says he was too sensitive – to doubt, to any kind of promise of security – to survive this ridiculous career or relationships. And yet, he did, and somehow completed it by connecting to a source he had no idea existed.

Around vivid descriptions of natural settings – the detail missing in the band story here in the minutiae of flora and fauna he encounters in suburban Sydney, in remote Northern Territory, in more crowded American and European environments – the real story of this book is the ripples out from Moginie’s adoption when only a few months old.

Growing up undoubtedly loved, even if, as it was for so much of the postwar generation, the physical and actual language, is never found or displayed, Moginie is of place but also not. The revelation to him in adolescence of the adoption is casual and then not talked about for years, and he tells himself for a long while that it doesn’t change anything. After all, why should it? But the slowly dawning realisation that it underpins his sense of impermanence can’t be denied.

So, he chips away in front of us at the foundations of his life as the band blossoms, as his skills expand, as success grows, ebbs, reconfigures. He is someone looking for the nugget of truth in the stories we tell ourselves even as we know them to be questionable. But he becomes someone who wants to believe in something intangible yet seemingly very real, in this case the idea of roots no matter how long obscured having a hold on us.

It’s a tricky path to walk, in the writing as much as in the living, and in both cases Moginie doesn’t always manage it smoothly, his self-recriminations frank. But equally frank is his joy and deep satisfaction in the connection he makes with his birth parents and their children.

That doesn’t mean the music and the career he’s built is of no importance in the face of something supposedly more “valuable”. For one thing, the language of play and connection along with a physical presence enabled by that career, precedes his emotional connection with the land of his parents. And music’s ability to be his exterior as well as interior, resonates on most pages, bringing him what can in the end pass as security.

Indeed, The Silver River is a reminder that everything of us is entwined, whether we know it or not, whether we make sense of it or not.