By Tony Hillier.

Like each previous release, the new waxing from this prodigious and prolific performer is significantly different from the one that preceded it. While it could be considered a companion piece to 2012’s Concerto of The Greater Sea, which had the oud ace out front of Richard Tognetti’s Australian Chamber Orchestra, Live At The Sydney Opera House is arguably a grander and bolder undertaking than that album or even any of his three recordings in New York with various giants of American jazz or his 2016 tour de force World Music, on which he played no fewer than 50 different instruments.

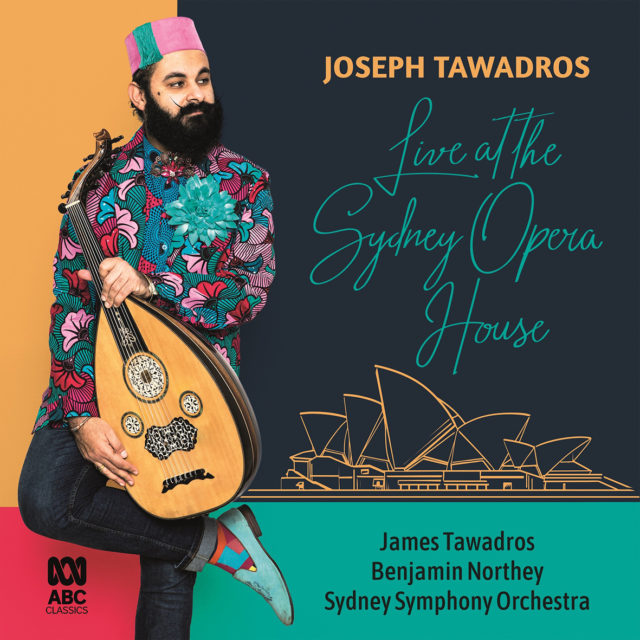

Aussie-Egyptian oud maestro Joseph Tawadros has played the Arabic lute in places and in settings in which it has rarely, if ever, been heard before. Live At The Sydney Opera House not only takes him and his instrument to the country’s most hallowed concert hall, following an appearance at the Royal Albert Hall’s prestigious Proms in London, but it also extends his astounding record of new album releases to seventeen years in succession.

Recorded live out front of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra (conducted by Benjamin Northey), the 76-minute concert features the world premiere of Tawadros’s 3-part ‘Concerto for Oud and Orchestra’, alongside re-arranged works from earlier studio albums. The set not only proves the player’s capacity to interact symbiotically with a full symphony orchestra, but demonstrates once again the extraordinary textures and range of his instrument and the virtuosity and variety of his playing and composing, to incorporate, with no trace of contrivance, traditional Middle Eastern modalities (maqam) with classical and baroque music and jazz, blues and folk elements.

Apart from exhibiting his own individual brilliance on tiny riqq tambourine and bendir frame drum, Joseph’s ever-dependable kid brother James plays a pivotal link role in providing a steady platform for the orchestra to drift over.

Tawadros’s ‘Concerto For Oud and Orchestra’, which occupies the opening 28 minutes of the concert, not only showcases the instrumentalist’s towering technical prowess, but equally saliently his ability to engage emotionally and energetically in such a setting. Orchestrated by Jessica Wells, the three movements are all in the key of C and in a combination of traditional fast-slow-fast structures, with melodies utilising the entire fingerboard and yet are distinctly different. In ‘Movement 1’ the oud enters, with full orchestration, in unusually low register and ends at the high end with similar accompaniment. ‘Movement 2’ starts with sombre oud figures before slowly building momentum with the SSO’s strings, then horns to the fore. The third and most impressive movement starts with a relative bang but has a quiet centrepiece featuring truly mesmerising oud tremolos and arpeggios before building with the orchestra to a spectacular finale.

Some inspired arrangements of pieces from Tawadros’s 2014’s release Permission To Evaporate take pride of place elsewhere. Jules Buckley’s reconfiguration of that classic album’s title track commences with harp and oboe in tandem before oud steps in majestically with the main melody, and closes with equally sublime Celeste. ‘Eye Of The Beholder’ benefits from a fuller and richer orchestral arrangement.

Joseph T’s oud playing in ‘Constellation’ is truly stellar, his slide phrases magically melding with ringing harmonics. A variety of Arabic rhythms drive James T’s ensuing tambourine tour de force. The brothers’ solo party pieces morph into a magnificent re-invention of ‘Bluegrass Nikriz’, in which the American West, conveyed by an Aaron Copeland evoking symphony, meets the Middle East while switching between 4/4 and 7/8.

Alternating time signatures also mark a dynamic curtain-closing rendition of ‘Constantinople’, in which Tawadros senior’s inner rock shredding fantasies are punctuated by several tambourine breaks from his bro of kit-drum intensity.