By Chris Lambie

For many, the Australian desert is the sound of didgeridoo and clap sticks. Or the robust drum beat of Midnight Oil’s Rob Hirst echoing the rhythm of corrugated outback tracks. When I think of Borneo rainforests, delicately woven notes of the sapé (a boat-shaped lute) take me there. Local legend Mathew Ngau Jau is to sapé what BB King was to blues guitar. An illustrated image of the now 72-year-old features in the Rainforest World Music Festival logo. The annual event is held at the picturesque Sarawak Cultural Village (from June 20-22 this year). Mathew’s association with the festival has endured over its 27-year history.

By the late 90s, with the passing of many Sarawakian exponents, ancient songlines were in danger of being lost to the past. Mathew was encouraged and supported to promote and preserve the heritage beyond the villages. He is known as ‘Keeper of the Kenyah Ngorek Songs’. His Lifetime Achievement Award was delivered in 2024 at the 19th BOH Cameronian Arts Awards ceremony in Petaling Jaya.

“I am Orang Ulu Kenyah,” he states proudly. The Kenyah people are one among 26 Orang Ulu (upriver) tribes. From a large family, Mathew learnt to sing and to play without formal lessons. Adults and children in the village worked long hours for survival – fishing, farming, hunting and building. “[As kids], we were doing our work on our own, actually,” Mathew recalls. “So, no teaching how to play or to make sapé. We just watched our uncles doing sapé, to follow suit.”

From observing elders including his late uncle Uchau Bilong, Mathew went on to play, build and decorate instruments for himself. The pair formed music group Lan E Tuyang, showcasing music and dance from village longhouse communities at the first ‘Rainforest’ festival. International tours followed. Mathew has since performed across Asia, Europe and the US.

From duo format, the line-up now varies to include Mathew’s son, nephew or local artists from the region. For RWMF 2025, Mathew has formed an ensemble featuring members from the Penan community, among others. The name Lan E Tuyang translates as ‘true friends’. Headhunter times ended long ago and tribal groups now peacefully join to embrace each other’s unique heritage. Mathew says, “The music brings all groups together. This time I have a very big group with practitioners from different areas. The Penan people are an ethnic group who have never been exposed internationally. They will join me to show their music and dance.”

Although Mathew himself no longer performs the warrior dance of his people, many young ones now recreate the graceful moves on stage and at workshops around the festival site. Local zithers, nose flute and percussion enhance the romantic sound of the past.

With the sapé’s popularity revived, demand for the instruments has grown. A new generation has learned the craft of creating them. Mathew explains, “The sapé is made from a single piece of wood. It used to take a month or more to make one, but with modern machines only around two weeks. It is not that easy now to find the wood, like 20 or 30 years ago when I started.”

Sapé originally had only 2-4 strings. New models bear six or more. “In older days with the healing ritual of the shaman, the strings were fashioned from the fibres of a jungle vine. From the iman tree, a type of creeper from the jungle. Like hair, black in colour. Then it changed to fishing line and now guitar strings. Today, players don’t like the big, bulky ones we used to have. Because now they mostly play with the pick-up,” he laughs. “I’m very more to the traditional and the younger one seem to enjoy the new ways of evolution of sapé now.”

Popular band At Adau (featuring Mathew’s son Jackson Lian and nephew Ezra Tekola) fuse the old and new in instrumentation and song structure. Around 2019, Ezra began learning to play the nose flute from one of the last authorities on the instrument. “He’s very, very good now. Not many can play it,” says Mathew. The band’s exuberance is infectious, with audiences joining in with chants and dance. “At Adau are doing very fine. They started playing the traditional music then with some mix of the modern. It’s very good for the young ones because they can jam with it. Making from the traditional music into upbeat. There’s room for both.”

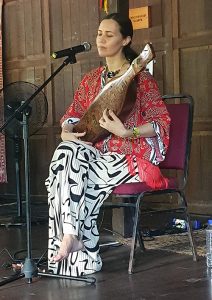

Mathew’s sapé student Alena Murang has toured widely as Sarawak’s first professional – and internationally recognised – female star of the sound. She sings in her own Kelabit and Kenyah languages. From gentle village folk song ‘Leleng’ to her own pop-folk compositions, she keeps the heritage alive and evolving. Her recently released single ‘Borneo Rain’ captures the essence of the local landscape and culture. Mathew says, “Alena and some other students, mostly girls, were quite young when they came to learn. The first time I taught the children, the old people were a bit sceptical about teaching women. It was not according to the omen where the girl wouldn’t play. But they seemed to be playing better, more beautiful than the boys. Since then, that’s the proof. They excel well. Alena is a good example. It’s a big encouragement, so many girls are open to playing now. When the old people see that the girls play well, it changes their mindset. I feel very proud because it’s not only me, but so many young people now play sapé.”

Australia-based young Kenyah performer Koleh recently appeared at WOMADelaide. It’s also become common to hear amplified sapé music.

“OK. That’s another one,” Mathew says. “Now it’s acceptable. No problem. They like it. Sapé can be very loud now. The young ones prefer it. But in the village, we always play the acoustic, real sapé at night, you see? Whenever we have any festival or event, so we have to have sapé. It wouldn’t’ be complete, lah, without sapé.”

That distinctive trickling tone is one of the most evocative and soothing you could hear. It conjures the inviting mystique of the rainforest, “Exactly.” Mathew agrees. “The birds, the jungle, the waterfalls. The sapé really blends to that sound. In the olden days, we didn’t have any doctors. So people depended on the shaman. They would play the sapé to cure the sick people. The sound is like, ‘Relax yourself’. For people in the city, it keeps you still. When I travelled to Rome, they invited me to the hospital. The doctor asked me to visit all the rooms and play. I don’t know if the patients liked it or not, or were curious, but they tried to open their eyes when they heard the sapé.”

A man of many talents, Mathew enjoys spending more time these days on his visual art. His designs adorn instruments, décor and paintings with intricate Tree of Life and other ancient motifs. The Rainforest festival introduces local culture to people from other parts of the world – guest musicians and fans alike. Just as visitors are welcomed on communal longhouse verandahs. Mathew’s travels have broadened his own taste in music. He laughs, telling me, “Now because I visit friends in the States, I tend to play sapé in the Country songs.”

Another honour was recently bestowed on Mathew. He and Alena Murang were chosen to be featured in the Hall of Fame at the Malaysian Pavillion for World Expo 2025 in Osaka. “The government appreciate you. There’s been hard work and a lot of challenges to keep my sapé going. It’s not for me, but for my people.”