By Michael Goldberg.

Fifty years on the White Album sounds better than ever.

I was 15, lying on my back on the green and white shag living room rug, a few feet from my best friend Dave, staring at the ceiling of the Eichler house he shared with his parents and younger brother in Terra Linda, a Marin County suburb, only I wasn’t seeing the ceiling. What I saw was a weeping guitar and a hunter named Buffalo Bill, a “warm gun” and a blackbird “singing in the dead of night” – hallucinatory visions prompted not by drugs, but rather, the Beatles’ latest creation, the not-yet-released album The Beatles, soon to be known as the White Album.

Radio on. It was Saturday, November 23, 1968, two days before the album’s U.S. release, and an FM station was playing all the songs on the album in random order, over and over, and nothing but, all weekend, and Dave and I were gonna to do nothing but listen, dig the hip new sounds of a band we were both obsessed with, the band we knew was the best in the world.

The thing about the White Album is that with the first song, McCartney’s Chuck Berry/Beach Boys rock ‘n’ roll parody, “Back in the U.S.S.R.,” we are brought into the Beatles surreal musical world, a sonic magical mystery tour of a world which, as Jon Pareles wrote recently in the New York Times, takes us through a wide range of music styles, each stamped with the Beatles’ unique imprint, that include “blues, country, doo-wop, parlor songs, 1920s jazz, psychedelia, musique concrete, orchestral easy listening, Baroque harpsichord, bossa nova, Jamaican bluebeat, English brass bands, Bob Dylan” and the Beach Boys.

If you’ve heard this album and if you are familiar with the Beatles’ previous recordings, you know that Beatles’ songs all sound like Beatles’ songs. No matter what style they are parroting, their vocals, guitar and bass and drum sounds, are distinct to the Beatles. And that Beatles’ sound, is a sound millions of us love. Listening to The Beatles, we are able to enter the group’s world and it’s a world where we want to hang out. It’s a much better world than the one we actually live in. What I’m trying to say here is that for many of us, listening to The Beatles is much more than simply listening to an album. It’s a place we love to go. We loved to go there in 1968 and we still love to go there.

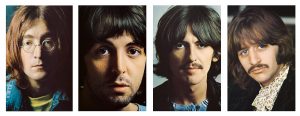

Is it even possible for those of you born in the’70s or later to understand how big a deal it was when a new Beatles’ album was released? The world is so different now. For many of us who were teenagers in the Sixties, the Beatles, especially John Lennon, were up there with such heroes as Martin Luther King Jr., Gandhi and President John F. Kennedy. We waited impatiently for a new Beatles’ song or album, and when it arrived, we dropped everything. I remember sitting by the radio waiting for a new Beatles’ song to be played again. Nothing was more important.

And so it was with the White Album, which is why Dave and I spent an entire weekend by his family’s stereo, listening reverently to the new songs.

The Beatles. The title and the cover were as modern as you could get. The simplicity of the title. Typically, a band’s name is used as the title of their first album, not their tenth. It was as if this were a new beginning. And the minimalism of the white cover with the band’s name embossed, also white, and a unique identifying number stamped in light grey in the lower right corner (perhaps signifying that each album was a unique communiqué from the Beatles to one of us).

This minimalism signaled the return to basics of the 30 songs and song fragments contained on the two-record set. A dramatic about face from the grandiose art-rock of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, an album mistakenly judged by some to be the Beatles’ best.

“On Sgt. Pepper we had more instrumentation than we’d ever had so it was more of a production, but we didn’t really want to go overboard like that this time…,” Paul McCartney said in 1968. “It’s a return to a more rock and roll sound. We felt it was time to step back because that’s what we wanted to do. You can still make good music without going forward.”

The White Album is not a concept album; the songs do not explore similar themes. Unlike Sgt. Peppers, but like the other Beatles’ albums, the White Album is an eclectic mix of lyrical themes and musical styles. When I was first listening to it in 1968, I thought it totally hung together; I had no idea at the time that it was really a collection of songs that, for the most part, were each written by just one of the Beatles in contrast to days past when Lennon/McCartney compositions were creative collaborations.

The songs were mostly written while the Beatles were on retreat with the Maharishi in Rishikesh, India. At least 19 of the 30 songs on the album are superb – Lennon showed up with some of his best material in years. And the other 21 songs, some of which are kinda marginal on their own (“Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da”), when heard in the context of the album are necessary and make the album work as a whole. They are part of that magical mystery tour of a world I wrote about earlier. For example, having an upbeat British music hall number, “Martha My Dear,” follow the slow ballad, “Happiness is a Warm Gun” and precede the equally slow “I’m so tired” makes for a much better listening experience than if “Happiness” had been directly followed by “I’m so tired.”

Is there a “best Beatles’ album, and is it The Beatles?” There are a number of contenders, but certainly The Beatles, long dismissed by some critics as a collection of mostly solo recordings (somehow implying that this made the songs inferior to real Beatles’ songs), or the beginning of the end of the band, or an overblown two-record set that should have been edited down to one disc, now sounds to me like one of the group’s best.

And so, fifty years after The Beatles was first released, we now have a six-CD Super Deluxe Edition that contains a stereo remix of the original album by George Martin’s son Giles on two CDs, a third CD with the “Esher demos,” 27 four-track acoustic demos that were recorded in May of 1968 at George Harrison’s psychedelic-painted bungalow, Kinfauns, located in what Rolling Stone has described as “the leafy London suburb of Esher.” There are also three CDs of alternate takes, as well as some songs that didn’t make it onto The Beatles, and a Blu-ray disc with high-definition mixes. Plus photos, a poster and a hardbound book (details here) filled with photos and info on each of the tracks.

And so, fifty years after The Beatles was first released, we now have a six-CD Super Deluxe Edition that contains a stereo remix of the original album by George Martin’s son Giles on two CDs, a third CD with the “Esher demos,” 27 four-track acoustic demos that were recorded in May of 1968 at George Harrison’s psychedelic-painted bungalow, Kinfauns, located in what Rolling Stone has described as “the leafy London suburb of Esher.” There are also three CDs of alternate takes, as well as some songs that didn’t make it onto The Beatles, and a Blu-ray disc with high-definition mixes. Plus photos, a poster and a hardbound book (details here) filled with photos and info on each of the tracks.

What you likely want to know is whether what’s here is worth paying $121.50 U.S. dollars (at Amazon as of early December 2018) or its equivalent in the country where you live and my answer: that depends. Depends on what? Depends on how hardcore a Beatles’ fan you are. Me, I subscribe to Spotify and all the music is available there; after listening multiple times I am not motivated to spend the cash to own the CDs.

I find it highly offensive that Giles Martin would have the audacity to remix the album, given that John Lennon and George Harrison are dead, and had no say in having their art tampered with. It’s as if Jeff Koons was allowed to mess with a Picasso.

Unless you are a completest, while some of the studio alternate takes are excellent (John Lennon’s “Julia,” for instance), I think the highlights here are the Esher demos, which you can get on the 3 CD 50th Anniversary Deluxe Edition which devotes two discs to Giles’ remixes and a third to the Esher demos.

Imagine the four Beatles sitting around a campfire sharing new songs with each other that in some cases are yet to be finalized – that’s the Esher demos. There is casualness to these demos – no pressure, no attempt at perfection. Highlights: Lennon’s “Dear Prudence” is exquisite, both the sparkling acoustic accompaniment and his intimate vocal. This acoustic demo contrasts dramatically with the final version of the song, a fascinating experimental track that manages to be both stripped down rock and avant-garde in the unusual spread of the instruments both across the stereo field and in terms of each instruments volume compared to the others. Harrison’s “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” with just acoustic guitar accompaniment and a lovely vocal. Lennon’s “I’m So Tired.” McCartney’s “Blackbird.”

While I’ve dug hearing these early demos, I don’t expect to be coming back to them again, and the same is true of the many studio takes. The Beatles, as released in 1968, is an extraordinary album and that’s what I want to listen to. If you have yet to hear it, get the 2009 version, or even the 1992 CDs – while some disagree, I think both sound quite good and are definitely truer to the 1968 mix than the Giles Martin remix. Sure, all the additional recordings that fill the 50th Anniversary set are interesting, essential even if you care about understanding to some extent the process that resulted in The Beatles. But if what you care about is hearing exquisite Beatles’ music, for $13.99 U.S. (at Amazon as of December 2018) you can own The Beatles, and that’s really all you need.

Let’s return for a moment to that Saturday morning back in November 1968, when I first heard the White Album. The rear wall of my friend Dave’s living room was floor-to-ceiling windows, and we both remember light flooding into the room as we lay on the rug, staring up, far beyond the ceiling, basking in the beauty of those new Beatles’ songs. As Dave now recalls about that day: “We were illuminated from within and without.”