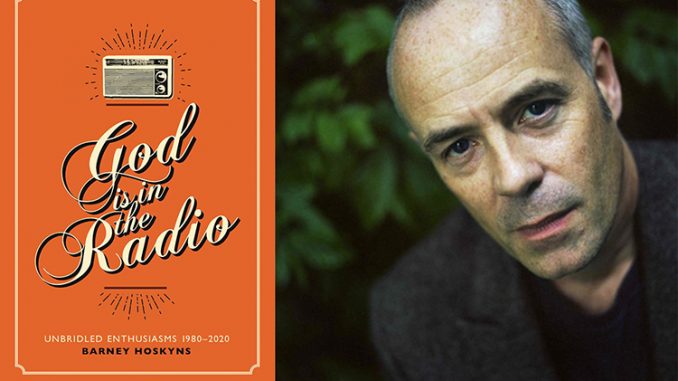

In his new book, God is in the Radio: Unbridled Enthusiasms 1980-2020, Hoskyns tells us why 50 of his fave artists mean so much to him.

By Michael Goldberg

Barney Hoskyns, a transatlantic friend who lives in London, is the author of a compelling new collection of his music writings, God is in the Radio. When I first saw Barney’s Facebook post some months ago about his upcoming book, I wondered about that title (which I found out comes from a Queens of the Stone Age song of the same name), but as I started reading the book, it made total sense. God is in the Radio is a love affair with music, music that has profoundly moved Barney—in some cases over many years. For Barney, like myself, perhaps for you as well, music does what religion does for some people. It can be a deep spiritual experience at times. God is in the radio? You bet!

For Barney, like myself, perhaps for you as well, music does what religion does for some people. It can be a deep spiritual experience at times. God is in the radio? You bet!

Barney writes in a sincere first person style much of the time. He’s an intellectual and well read; consider that he graduated from Oxford with a First Class (the highest honor) degree in English. To get a sense of his writing, dig this from his PJ Harvey profile: “Stories had been her most satisfying album to date – not least because it was her happiest yet. Trebly and sparkling, full of the euphoria of love and the mad energy of her part-adopted Manhattan, the album followed the fuzzy techno-murk of the equally great, Is This Desire? – a record implicitly haunted by her break-up with her sometime hero Nick Cave – like sunshine bursting through black clouds.”

He knows music and writes authoritatively about it. Here he writes about a Burt Bacharach three-CD box set. “Just as Bacharachian balladry offered a counterpart to Spector-esque pomp, so Dionne Warwick’s cerebral soprano defused the deep-soul sobbing of so many Sixties sirens. Not for her the hysterical melisma of much gospel, even if she was steeped in the stuff…”

And earlier in the piece: “But anyone who can’t hear past the cocktail-piano kitsch to what [Elvis] Costello calls Bacharach’s “sense of darkness” and “romantic doubt” surely has cloth ears. For here’s the point: as missing links between Rodgers & Hart and Lennon & McCartney, Bacharach and his principal lyricist Hal David transcended the conventions of Teen Pan Alley so effortlessly that their cool neoclassical peaks – “Make It Easy On Yourself,” “Don’t Make Me Over,” “Anyone Who Had A Heart” and so many more – tower over even the best songs of Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, Gerry Goffin and Carole King, and Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil. Only Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, whose work lay almost entirely outside the pop-ballad realm anyway, fully deserve to stand alongside them.”

Born and raised in the UK, Barney began writing about music in 1979 for Melody Maker, after graduating from Oxford. He joined the staff of the New Musical Express in 1983. Three years later he left the NME to write a book about soul music, Say It One Time For The Brokenhearted. He was Mojo’s U.S. correspondent from 1996 to 1999. He’s written or edited more than 15 books including 1996’s Waiting For The Sun: Strange Days, Weird Scenes & The Sound Of Los Angeles, which was nominated for a Ralph J. Gleason award. He currently writes and edits books and is Editorial Director at Rock’s Backpages, the online music journalism archive he founded in 2000.

When you read this book, it definitely helps to have access to a streaming music service because you, like me, probably haven’t recently heard some of the artists (Eddie Hinton? Lee Hazlewood?) Barney writes about. I would often launch Spotify and get the relevant song or album playing. And that’s a cool thing about God is in the Radio: it will likely introduce you to some artists you never listened to or took seriously. Jimmy Webb? Ron Sexsmith? Or provide an excuse to revisit all those Cocteau Twins albums you haven’t listened to in years.

Now don’t jump to conclusions. Barney also writes eloquently about many high profile artists: Sly Stone, Laura Nyro, the Rolling Stones, Stevie Wonder, the Beach Boys, Bobby Womack, Steely Dan and on and on. Fifty in all.

Now don’t jump to conclusions. Barney also writes eloquently about many high profile artists: Sly Stone, Laura Nyro, the Rolling Stones, Stevie Wonder, the Beach Boys, Bobby Womack, Steely Dan and on and on. Fifty in all.

The book is divided into two parts: The first is called Short Cuts,: and it’s followed by Long Players. Short Cuts are reviews. Long Players are lengthy profiles and essays. There are 25 of each. Now the Short Cuts are good, but it’s the Long Players that, for me, really sing. And my favorite piece in the book is an essay, A Song for Her: Amy Winehouse, that was written for Back To Amy, a book by photographer Charles Moriarty published in 2018.

Barney begins his Winehouse piece by talking about Donny Hathaway, who committed suicide by jumping from a 15th-floor hotel bedroom to the street below. He writes that not only did Winehouse record Hathaway’s version of Leon Russell’s ‘A Song For You,’ but she also sang two more of his songs during live performances. He notes that at the end of her recording of ‘A Song For You,’ Winehouse says, “Donny Hathaway, like… he couldn’t contain himself. He had something in him, y’know?”

It’s a setup, the next graph begins, “The notion that Hathaway couldn’t “contain himself” was a revealing one in the context of Winehouse’s own life and eventual death. Perhaps she heard something of her own restless desperation in his plangent tenor voice; possibly she was haunted by his suicide…”

Barney loves Winehouse’s key album, Back To Black. He writes that the day it came out in England, he sat in a car listening to the CD. “I was unable to move, startled by the greatness of what I was hearing: not just the raw power of the voice, not just the liberating shock of her lyrics, but the soul and sophistication of her new musician touchstones.”

Winehouse was, as we now know, a drug addict and an alcoholic. Barney became addicted to heroin in his early twenties but has been clean for decades. Still, he is quite perceptive in writing about addiction (his addiction memoir, Never Enough: A Way Through Addiction, is the best book about dealing with drug addiction that I’ve yet read), and here he zeroes in on Winehouse’s troubled pop star life. “While there was something refreshing about an artist who simply didn’t give a damn – who didn’t (appear to) care about tact – you had to wonder about Winehouse’s anti-careerist ‘authenticity.’ … Was it, in fact, just another mask designed to obscure the truth of the pain Winehouse carried and acted out through addiction – not only to chemicals (legal and otherwise) but to binging and purging, to tattoos and hair extensions? ‘The more insecure I feel,’ she once revealingly admitted, ‘the bigger [my] hair has to be.’”

It feels like one is getting the real deal reading the pieces in this book. Barney has been at this (writing professionally about artists and the music they made) for other 40 years, but he’s also taken a hard look at himself and the result is a writer who doesn’t bullshit, a writer who puts truth on the page.

* * *

Also Noted:

Guitarist/songwriter Michael Belfer cofounded one of San Francisco’s greatest punk bands, the Sleepers, and played in Tuxedomoon. His excellent memoir, When Can I Fly? (HoZac Books) is a deep dive into the late ’70s SF punk scene, which was riddled with hard drugs and fucked-up musicians (like Sleepers singer/lyricist Ricky Williams, dead of a heroin overdose in 1992) whose talent couldn’t save them. Belfer, who eventually kicked his own heroin habit, tells his harrowing story: he’s a talented musician who time and time again comes so close to achieving popular and financial success, but never does. Yet as an artist, both with his music (give the Sleepers’ “Painless Nights,” which can be streamed on Spotify, a listen) and in telling his heartbreaking story, he has achieved great success. His book is a keeper, and one hopes he’ll write more in the years to come.

Michael Goldberg, a former Rolling Stone Senior Writer and founder of the original Addicted To Noise online magazine, is author of three rock & roll novels including 2016’s Untitled.