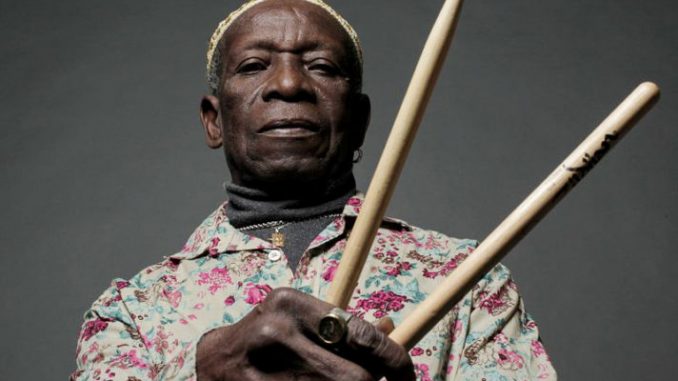

Tony Allen was an ace in the Afrobeat pack.

By Tony Hillier.

The pulse of Afrobeat may have stopped momentarily when drummer Tony Allen died suddenly in Paris on the last day of April, but the beat most assuredly continues in his wake.

Allen, who was 79, has left a significant legacy — if anything richer even than that of Fela Kuti, his partner-in-rhyme and co-architect in the genre that blended jazz with Yoruba tribal rhythm, funk, Highlife dance music and razor sharp social-political commentary.

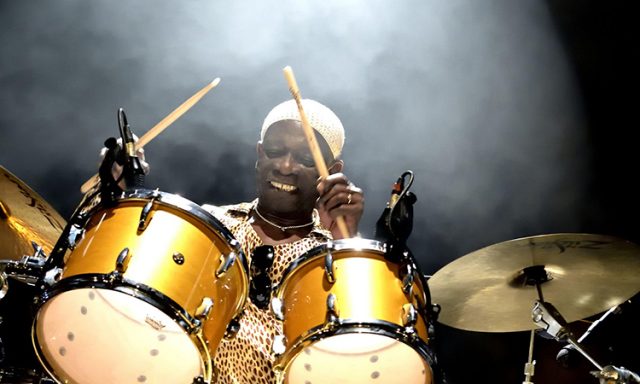

As drummer and musical director, it was Allen’s ultra-dexterous polyrhythmic rhythm that set up the platform for Nigerian and Ghanaian Highlife to morph into Afrobeat via Kuti’s Africa ’70 in the 1960s/1970s. And it was Allen who sparked a revival of the genre when he returned from a recording hiatus in the mid-1980s. Inspired by Allen, and subsequently bands led by Fela Kuti’s sons, Femi and Seun and others, Afrobeat has never been more popular or played more widely around the globe.

Fela Kuti is on record as having said that without Tony Allen, who taught himself how to play drums in his teens, there would have been no Afrobeat. Kuti’s progeny have acknowledged the support and friendship afforded to them by their father’s long-time drummer in past interviews with this correspondent.

Seun Kuti proudly told me before his shows at WOMADelaide in 2016: “Not everyone can count Tony Allen as their uncle. Uncle Tony and I have played a lot of gigs together.” Elder brother Femi, who in a separate interview recalled “Uncle Tony” taking him to school in Lagos when he was little, declared: “There’s simply no drummer like Tony Allen”.

In an interview I conducted with Tony Allen for the same article — he was sitting in with Seun Kuti’s Egypt 80 at WOMADelaide — the drummer ascribed his unique style as a legacy of being exposed to juju and other indigenous Yoruban music styles in his formative years, and then mixing those styles with American jazz. “Art Blakey and Max Roach were my masters of drums,” he declared.

While Allen always maintained that he didn’t invent Afrobeat per se, he asserted that his drumming was the genre’s backbone. He thought drumming should be tantamount to riding a bicycle. As he told The Wire magazine: “You have to use your four limbs, which was very rare among drummers when I was starting out.”

Tony Allen told me that when American soul legend James Brown, whose music was a seminal influence on West African musicians, visited Lagos he turned up a gig at Kuti HQ, The Shrine, to “try and understand my groove”. He recalled: “Back in those days in my country, I used to play drums all day long or all night long. People in Nigeria would have killed the band if they were not overtaken by Afrobeat live music.”

Allen asserted that Afrobeat was cemented after the band toured the USA in 1969: “The funk and jazz scene in the States gave us the vibes to step forward to another level.” He was as enthusiastic about Afrobeat then as when helping to create it with Fela Kuti four decades earlier: “It’s the only rhythm today that’s creating something,” he declared, adding “I wouldn’t be a drummer if I had to play something else. I don’t want to be a rock drummer, or strictly a jazz drummer.”

He also refuted any suggestion that Afrobeat was devised primarily as a platform for Fela Kuti to fire broadsides against the government. “The political and business context of that time made Fela fight and react against the corruption and the record music corporate companies associated with the local army dictator.”

However, despite his obvious respect for Kuti’s crusading zeal, the drummer indicated it was his musical partner’s rigid political stance that caused him to walk out on Fela and Africa 70 after the Berlin Jazz Festival in 1978. “I got tired of the entire mess with the organization. The music was not the main thing anymore … it was le vaudou [voodoo], religion and politics.” Allen said he last saw Fela in 1992, in Paris, where the drummer lived until his death last month.

While Allen recorded more than 30 albums with Fela Kuti’s Africa ’70, he has been equally prolific in recent years both as a bandleader and collaborator, releasing no fewer than seven albums either under his own moniker or with various projects in the past three years alone.

The latest release, Rejoice — a duo studio set cut with the legendary South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela in 2010 — was belatedly launched only a few weeks before Allen’s death and two years after Masekela passed away in 2018. Adding further irony to the timing, another giant of African jazz and fellow Allen collaborator, the great Cameroonian saxophonist Manu Dibango, died little more than a month before the drummer exited stage left.

Lamenting Tony Allen’s passing on Instagram, Benin-born afro-funk queen Angelique Kidjo, who utilised the drummer’s services on a track of her 2018 re-make of Talking Heads’ Remain In Light, observed that he had changed the history of African music.

Brian Eno described Allen as “perhaps the greatest drummer who ever lived.” Blur’s Damon Albarn, who made two albums alongside Allen as a member of the Good, the Bad and the Queen, was similarly effusive. The Red Hot Chilli Peppers’ bass ace Flea, who also spent time with the great drummer in London, hailed him as his “hero”.

Tony Allen, who reportedly modelled his superb technique on one of his heroes, Art Blakey, paid tribute to the great American jazz drummer and bandleader with a 2017 Blue Note EP. In the same year, a long-player for jazz’s premier label, The Source, saw the drummer return to his Afrobeat roots, with a big band approach, accompanied by a gun octet of French instrumentalists.

In the last decade of his life, Allen was the antithesis of one-dimensional. Apart from Afrobeat, he covered genres ranging from hard-hitting American jazz to cruisy French pop, from downbeat indie rock to electronic techno.

While the legendary drummer was fascinated by new music, his preoccupation was keeping the spirit of Afrobeat alive and passing on his knowledge to the younger generation. As recently as last month, he said in an interview that his plans for 2020 encompassed working on an album with young musicians from Nigeria, Paris, London and the USA.

Tony Allen’s services to Afrobeat, in particular, and the music world, in general, will be sorely missed.

* Tony Hillier’s review of Tony Allen & Hugh Masekela’s collaborative album, Rejoice (out on the World Circuit label), will appear in the July/August print and digital issues of Rhythms.