By Des Cowley

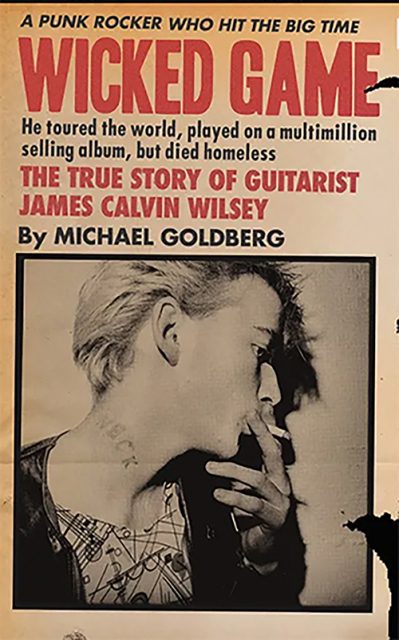

WICKED GAME: THE TRUE STORY OF GUITARIST JAMES CALVIN WILSEY

By Michael Goldberg (Hozac Books, 2022)

American music writer Michael Goldberg will be familiar to readers of this magazine. A former senior writer at Rolling Stone, his regular Rhythms bulletins on the unending stream of Dylan bootleg releases are mandatory reading. If Dylan can be said to embody the musical centre, then Goldberg, with his new book Wicked Game, has set his sights on the outfield, focusing his attention on the peripheral, the lost. Unlike Dylan, the late guitarist James Calvin Wilsey is anything but a household name. And yet, who among us could fail to recognise his trademark sound: the laid-back, smoky, romantic guitar-intro that ushers in Chris Isaak’s ‘Wicked Game’. It’s a sound once heard, never forgotten, played by a man routinely dubbed ‘The King of Slow’.

Goldberg begins his book with Wilsey’s death, at age sixty-one, in late December 2018. Wilsey had been sleeping rough in Los Angeles, homeless, his body ravaged by years of addiction, barely recognisable to the few friends who’d kept up with him. It was a sad, ignoble end, standing in stark contrast to accompanying photographs that show a young, smiling Wilsey, taken in 1977, at the outset of a promising musical career. What happened? As Goldberg says: “Jimmy’s story is the story of the American Dream, which always contains both dream and nightmare.” Such are the twin poles around which Wilsey’s life revolved.

While not a close friend, Goldberg establishes early on that he first met James Wilsey back in 1982, when he was a member of the second version of Silvertone, the band he’d formed with Chris Isaak. As Goldberg says: “To see Silvertone live in the ‘80s was to experience rock & roll for the first time, the Beatles at the Cavern Club, 1961, that kind of excitement… Isaak and Jimmy had a spellbinding charisma. Together, they were invincible.” In the intervening decades, Goldberg struck up a friendship of sorts with the guitarist, profiling him in Guitar Player, writing a feature on him for Rolling Stone, hanging out with him on occasion.

From there Goldberg dives back into Wilsey’s past, recounting his earliest years spent in a variety of locales: Indiana, California, Kansas, Missouri. He loved music from the get-go, and took to playing an old Harmony steel-string he’d found laying around the house. By 1974, he graduated to a 12-string acoustic guitar (“because Bowie played one”), before upgrading to a 1964 Stratocaster, then on to an early ‘60s hollow-body Gibson electric. But it was his move to San Francisco in 1976, at age-19, that spelled the end of his apprenticeship. The city’s first punk club, the Mabuhay Gardens, was open for business, and a year on Wilsey landed a spot with local punk band the Avengers, ironically holding down the bass chair. To this day the Avengers remain revered, arguably the best punk band that emerged on the west coast. Yet, despite being support act for the last-ever Sex Pistols show at Winterland in 1978, the Avengers imploded the following year, without ever having released an album. It’s one of the strengths of Goldberg’s book that he documents this burgeoning and influential wave of San Francisco punk.

The story of James Wilsey is, at heart, a parallel story of talent and addiction. As Goldberg notes: “Hard drugs were part of the SF punk scene from the start.” Wilsey was an early adopter, and for much of his life, aside from a series of tumultuous relationships, it is the line that connects the dots of his career. After the Avengers, he relinquished punk, finding himself more attuned to the sounds of Gene Vincent, The Sun Sessions, Eddie Cochrane. With his newfound musical taste, it was inevitable Wilsey would eventually cross paths with San Franciscan newcomer Chris Isaak, who’d grown up on a steady diet of country music and rockabilly. From 1980, when they met, until their creative separation in 1993, Wilsey’s ‘less is more’ approach was the defining sound of Isaak’s music, from first album Silvertone (1985) through to 1993’s San Franciscan Days.

Wilsey was an old-school guitarist. While he might have schooled himself on punk, his influences were eclectic and classic, ranging from Elvis’s guitarist Scotty Moore, Duane Eddy, the Shadow’s Hank B Marvin, Don Rich, and Link Wray. In the end, he was more than the sum of his parts. A master of minimalism, he “was low key and cool in his demeanour, but his heart and soul were in the notes he played.” Post Isaak, Wilsey would record just one solo album, 2008’s El Dorado, a masterwork of sonic western landscapes, sadly ignored at the time of release.

In Michael Goldberg, James Calvin Wilsey has found his ideal chronicler. Goldberg’s thoroughly researched account, combined with his devotion to his subject, has given form and shape to a life that was, for the most part, incomplete and fragmentary. Despite Wilsey’s long-term residency in both San Francisco and Los Angeles, his passing went unnoticed in the local press. This, as Goldberg reminds us, for an artist “intrinsic to the success of a multi-million selling album, and an international hit single that is still being streamed millions of times each month. No funeral. No mention at the Grammys”. In other words, his was a story destined to fall between the cracks, save for Goldberg’s investigative sleuthing. The business of music biography favours the winners, the successful. Life’s tragic failures – think Jay Gatsby – are more likely to be found in literature. With Wicked Game, Goldberg turns this maxim on its head, showing that the dichotomies of success/failure can hedge on the throw of a dice. Goldberg elects to explore what lies between, giving voice to the forgotten. In doing so, he delivers a complex morality tale, tinged with melancholy, that has all the drama and hallmarks of fiction.