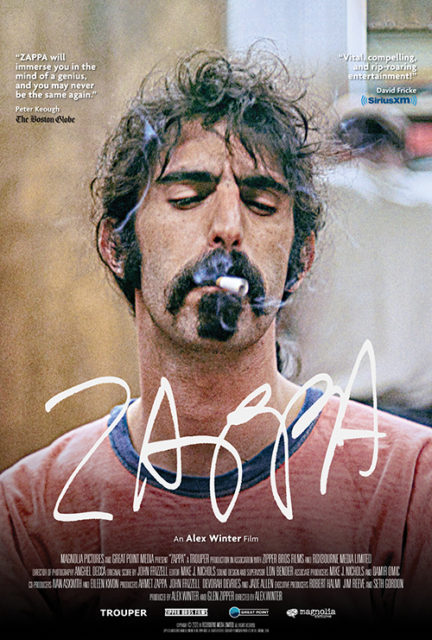

Alex Winter‘s new documentary on Frank Zappa screens nationally in cinemas from February 18.

Brian Wise spoke to Winter about the film in this in-depth interview.

ZAPPA (Umbrella Entertainment)

While it was difficult to resist the temptation to ask director Alex Winter about his other life as an actor – particularly as Bill in the wacky Bill & Ted movie franchise – it occurred to me afterwards that such an experience might have helped him appreciate Frank Zappa’s life and work even more.

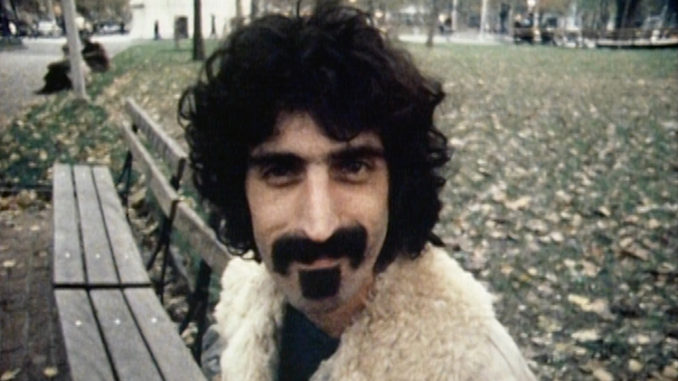

One of the most prolific musicians of the 20th century, Zappa’s music and his lyrics challenged conventions, shocked people, was constantly inventive and highly influential. While the closest he came to a hit song was ‘Valley Girl’ in 1982 (No.32 in the Top 100) and his only Top 20 album in 27 years was Apostrophe in 1984. By the time he died in 1993 at the age of 52, Zappa had released literally hundreds of recordings. He had also become a strident crusader against censorship in music and a political activist revered in the Czech Republic. Yet one of the most striking aspects of Zappa’s work was his humour which I was lucky enough to experience first-hand.

In June 1973 Zappa and The Mothers (of Invention) band toured Australia for the first time and appeared at Melbourne’s Festival Hall. The amazing ensemble consisted of some crack musicians including George Duke on keyboards, Jean Luc Ponty on violin, Bruce Fowler on trombone and Ruth Underwood and Ian Underwood on percussion and woodwinds respectively. I still recall Zappa constantly stopping the band and making them restart songs, for some reason know only to him. (George Duke once told me the story of how Frank also enjoyed putting musicians on the spot by demanding unexpected solos but that after Duke ripped out an incredible spontaneous solo he was spared from then on).

Apart from the incredible musicianship, I also recall rolling around in hysterics when he performed songs such as ‘Don’t Eat The Yellow Snow’ and ‘Nanook Rubs It In’ (and, no, I hadn’t been smoking jazz cigarettes).

“Ooh, that was a good one,” says Winter of the line-up when we catch up via Zoom to talk about the new documentary. “That’s fantastic.”

“That didn’t change as the years went on, that’s for sure,” he notes when I mention that Frank kept stopping the band.

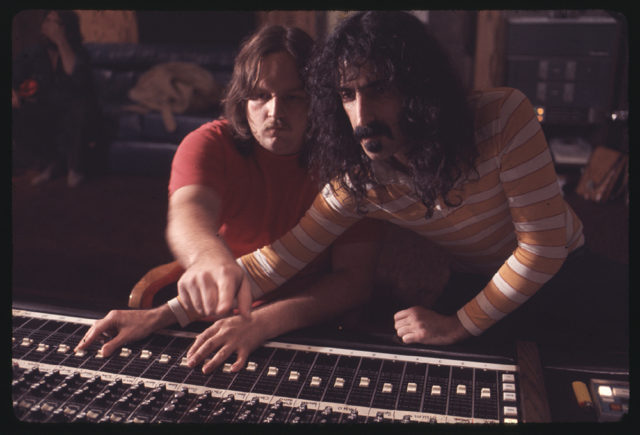

In Zappa, you can see plenty of Zappa and his bands in full flight. Winter and his team were given unrestricted access to Zappa’s archives thanks to Frank’s widow Gail and the estate. There is a glimpse of the massive archives which gives you an idea of why it took Winter and his crew some years to trawl through them.

“It was somewhat mythical, but I didn’t realize quite how expansive it was,” says Winter when I ask about the vault that housed Zappa’s archives, “and I’m not even sure the family really understood the depth of what was there because a lot of it wasn’t marked so it was kind of a journey of discovery for everybody.”

Gail Zappa is a major interviewee, along with many friends and collaborators who appear in the film, including Ian Underwood, Steve Vai, Pamela Des Barres, Bunk Gardner, David Harrington, Scott Thunes, Ruth Underwood, Ray White and others

“I was a big fan and I grew up in an era that was very Zappa heavy,” admits Winter when I ask him what drew him to Zappa as a subject for documentary. He had already made non-music films such as Showbiz Kids, The Panama Papers and Deep Web. “I grew up in the States, largely in the ’70s and he was a real cultural type to us growing up. He was more than just a musician, he was kind of a leader of social, political, sexual culture as well, and he was hilarious and he was a great artist. Everybody’s older brother had a giant Zappa poster in their room, and you grew up with a keen awareness of who he was.

“What made me want to make the doc was beyond that, to the degree that I always found his life and the events of his life to be incredibly fascinating, and him to be a really complicated and interesting person who lived at a very interesting period in our history. So, those types of characters make good subjects.”

“I mean look, you know Zappa, you know the world, and it was not easy and we wanted to get it right,” responds Winter when I mention that the film took years to make, “and we wanted to tell a story and make a movie that was entertaining but complex and kind of epic in its scope to encompass aspects of his life – not to tell just the sort of linear bio story and certainly not to make an album to album music doc, but to tell a kind of epic drama about an artist, who lived in a particular period of time and Zappa’s a complicated fella so it’s something that we really wanted to just take our time with and to figure out.”

“I was really interested in telling his intimate story if possible, especially given the fact that Zappa was so enigmatic and I did not want the film to feel like an outsider’s point-of-view,” says Winter when I ask him about the approach that he decided to take in telling the story. He no doubt could have found a very high-profile narrator.

“I really wanted it to feel like we were experiencing, as best as possible, what Zappa’s life was like from his own perspective, without cheating, without pretending it was a first-person narrative but using as much material as we possibly could to convey his interiority, to convey his life and his worldview. And Mike Nichols, the editor, and I really felt strongly that the vault material was giving us such an intimate way in. We found shelves and shelves of never-before-heard or seen interview content with him, a lot of which was just him down in the basement, shooting the breeze with friends and associates and being very honest and forthright about the things that were going on in his life, and we really liked that stuff. So, one of the first things we did was built a timeline of a narrative, comprised of all that material and that was very helpful to us in guiding the approach.

“The other thing we wanted to do is kind of convey Zappa’s style, musically and his film style because he was an avid film-maker, and his editing style was really specific so that was a guide for us as well.”

“Oftentimes people called him a workaholic,” replies Winter when I mention how prolific Zappa was. (I once counted that there were at least 210 Zappa albums officially released and it is probably way more now). “It wasn’t a term I was interested in investigating too thoroughly in the film though we do mention it, we don’t shy away from it. He was someone who was incredibly committed to the life that he set out for, all the way back in his teens and to him, making art was of paramount importance and it’s what he wanted to spend as much of his waking hours doing as humanly possible so he made a lot of stuff and his output was prolific, but it also had a really high caliber of quality because he was such a perfectionist. Now, I don’t think there were too many popular artists from that era that had a life like that. I think Prince is somewhat similar and I think there’s a few others in other mediums that are similar, but he was pretty unique in his world.”

While Zappa’s albums with the Mothers of Invention contained material that these days might be considered politically incorrect, much of it also challenged conventions. However, Zappa was a fierce defender of free speech and spoke up publicly for other artists at a Senate hearing (along with John Denver and Dee Snyder).

“Essentially the three of them went to battle with all of these adversaries and succeeded,” explains Winter. “I would argue they succeeded largely because of Zappa’s testimony which was incredibly eloquent and persuasive.

At one stage during the hearings, Zappa suggested, with no trace of sarcasm, that song lyrics should be printed in full on the covers of albums. The committee members took it as a serious suggestion.

“I know, I know. They really felt a boot on their neck,” says Winter. “They were concerned that the art itself was going to be censored and that they wouldn’t be able to actually put out their work, so he was looking to try to create or show the willingness to create compromise.”

Of course, Zappa had a few less likeable characteristics which Winter’s film doesn’t really shy away from. I mention that his crude humour with the Mothers could be considered offensive these days.

“I mean, unless you listen to your average rap artists!” Winter retorts. “I think that that Zappa was a man of the times from the standpoint that essentially. He was a multifaceted person. There was the very kind of patriarchal, old school, Italian dad, but it was also the sexual revolution and he was really kind of ahead of the curve of even a lot of the artists around him because he was a little bit older than a lot of the artists around them, and so he spearheaded the groupie movement, you could argue. Pam Des Barres, who came up and, in that group,, also spearheaded that movement and so, I did not want to cast aside some of the more negative aspects of his personality and just blame them on the times, I think that’s a bit of a cop-out. I really did want to focus on what kind of person does that, that has a genuine interest in his wife, who he was extremely close with and they ran a business together and it was not just a bad marriage that they pretended existed. I mean, they really were very entwined, and he was very devoted to his kids and yet, he would take off on the road and the rules were completely thrown out the window. I found that interesting and I wanted to look at it.

The other important thing about Zappa’s career, towards the end of his life, was his involvement in politics, particularly with Vaclav Havel and the Czech Republic.

“I remembered it when it happened and I thought it was very impressive and very interesting,” says Winter. “What I did not realize until we got into the archival media, was how devoted he was to developing a greater understanding of world events. I found it incredibly impressive that he wasn’t just a kind of armchair, political pundit, kind of spouting off on what was going on. He went to Moscow and he went into different places of the world to try to roll up his sleeves and see what he could do to help and also to understand what was going on globally. That was something that was a surprise to me. I knew a lot about Zappa growing up, I did not know that and it was a very intriguing.”

How does Winter think Zappa would have managed the past four years in American politics had he been alive?

“I think that it’s impossible to know,” he responds, “because he was very much a man of his own values and his own mind, and I think that everybody who was a fan likes to claim him, whatever political persuasion they are. I understand why: he’s a really compelling political thinker – or he was – but the only thing I know about him that seemed to be steadfast from his childhood all the way through until the end of his life was, he was very, very, anti-authoritarian, very pro citizens’ rights, very much a believer in voting rights, something that he was at the forefront of from the very beginning of his music career. He was always, as I’m sure you remember, putting on his albums and trying to provoke people to get out and vote and stand up for their own rights. So, someone who was anti-fascist, anti-authoritarian, pro citizens’ rights, I think would have quite a bit to say about where the world is right now.

The documentary is timely given that Zappa has faded into past a little; however, he was an incredibly important musician, not just because of the complexity of the music that he made and the diversity of the music. How does Winter assess his importance in those ’70s and ’80s?

“I’m loathe to try to pass myself off as an authority on Zappa,” replies Winter, “and I know that’s not what you’re asking me to do but I would just caveat it greatly that this is one guy’s opinion. I was a kid in the ’70s. I didn’t totally get the music. I enjoyed it but I wasn’t a fanatic, right, for Zappa. I didn’t really get Zappa until the ’80s and really probably even possibly the ’90s. I enjoyed listening to it but there was sort of a convergence of the more rock-oriented stuff, the Synclavier stuff and the orchestral stuff that really opened a door for me and once I understood – and again, this is personal, this isn’t an edict – but for me, Zappa wasn’t a rock and roll musician at all. He really was more of an avant-garde composer.

“I realise now that that’s why Gail let me make the movie when she didn’t let other people make the movies. I didn’t know Gail at all, I knew the kids a little bit, and I didn’t know what she did or didn’t think about her husband at all. But the very first time I met her, I told her my thesis, which is that I didn’t really get Zappa until I realised he wasn’t a rock musician, and he was really an avant-garde composer. She said, ‘That’s it. You’re absolutely right.’ I think she shared some degree of my perspective and beyond that, she had much of her own perspective but that was really what clicked for me. And once I perceived him that way, it opened up all of the music. It opened up all of Zappa to me.”

Does Winter you have a favorite piece of music or a favorite Zappa album.

“Gosh, I really do like so much of it. I love Dogs Breath Variations. I love everything from the whole span of his work. I love ‘Willie the Pimp’, I love enormously. If someone put a gun to my head and said I can only have one album…. It’d be a Desert Island Disc for sure, though I would be very disappointed to not be able to bring Yellow Shark along as well.

“But I really do love so much of it. I love Over-Nite Sensation and Apostrophe. You know why the fans talk about the big note and this idea of it all being one composition, because it kind of was, but you could say the same for Stravinsky, you could in a way say the same for Coltrane. I think there are certain composers who you feel like their work is a giant piece of work and that’s why it’s hard for me to break out Zappa’s stuff in that way.

In the documentary there is some film of Zappa in Australia but many here would recall Norman Gunston’s famous interview with him recorded in Los Angeles in 1976. [Gunston, the brilliant creation of comedian Gary McDonald caught many off guard with his disarming interviews]. During the interview Gunston took out a harmonica and asked to jam (or as Norman said, ‘In America you call it jelly’). When Zappa played the Hordern Pavilion in Sydney he invited Gunston up on stage.

“I may have. I mean honest to God, I spent so many years on this and watch so much stuff, I can’t the tip of my brain recall, but it sounds vaguely familiar,” says Winter. “That’s great. I love that.”

Winter has made a very successful transition to directing, although the Bill & Ted series remains a blockbuster.

“I started acting as a child and even as a kid I was interested in writing and directing films and so I went to film school for college, I didn’t go to college for acting and I started working professionally right out of film school. My acting career was much more public facing than my film work. It’s just the nature of that kind of work so they were always running in tandem and Bill & Ted 3 was fun because it gave me a chance to act again in public and I’ll probably do a little bit more of that here and there, alongside the film work. I like them both.”

Many music documentaries tend to be promotional videos but Zappa brings an in-depth look at a musician whose music deserves to live on. Of course, his son Dweezil is carrying the torch but this should bring a re-assessment of Zappa’s career and contribution to music.

“Thanks so much for the chat,” says Winter as we finish our interview. “It’s great that you got to see him and got to see him in such a special era too. That’s really lucky.”

Zappa is showing in cinemas nationally from February 18.