By Michael Goldberg.

Nearly 43 years after its release, Blood On The Tracks, stands the test of time.

I remember we were in the living room of the three-bedroom apartment on Sacramento Street. That was in San Francisco. The old San Francisco, long, long before the dot com boom. It was winter, January 1975. It was an old apartment. It was an overcast day. My best friend Dave and I had rented the place for less than $200-a-month and found a third roommate, a guy named Howie who, like us, was a serious music fan. The apartment was on the second floor; you walked up a flight of stairs to get to it. I had never lived in San Francisco before, and as it turned out, I only spent a couple nights in that apartment on Sacramento Street – and soon enough I’ll tell you why.

It was in the afternoon, and we were in the living room, the three of us, gathered around my stereo. I had the new Bob Dylan album, Blood On The Tracks. The album was a hit for Dylan, soon to reach number 1 on the Billboard 200 chart, and earn a gold disc (500,000 sales) on February 12, 1975, three weeks after release. Today it is considered one of Dylan’s finest albums. In a 2012 Rolling Stone reader poll, Blood On The Tracks was voted Dylan’s best.

In the weeks following the album’s release, reviews were mixed, and it was not heralded as Dylan’s best album. Writing in Rolling Stone, Jon Landau said he liked Dylan’s singing, and that the “writing is the source of the record’s power,” but spent much of his review trashing Dylan as a “record maker,” noting: “The record itself has been made with typical shoddiness.” Landau also wrote that Blood On The Tracks “would only sound like a great album for a while” and was “impermanent.”

Greil Marcus found the “backing on the album” to be “merely functional, undistinguished save for Dylan’s harmonica,” but still he wrote in a February 1975 review for San Francisco’s City magazine, “It is a great record: dark, pessimistic, and discomforting, roughly made, and filled with a deeper kind of pain than Dylan has ever revealed.”

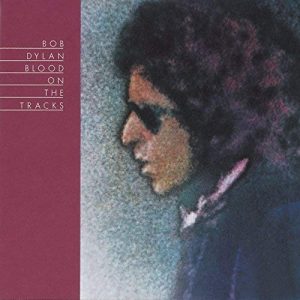

I had not read any of that when I stood in the living room of that Sacramento apartment and removed the vinyl disk from the sleeve. My friend Dave took the album cover from me to check out the strange, blurry cover photo of Dylan, and Pete Hamill’s poetic liner notes. I put the disk on the turntable.

Back then, and by that I mean starting around 1964 and on into the ’70s, the release of a new album by one of the greats – and Dylan was unquestionably one of the greats – was a big deal. I mean a really BIG DEAL. In 1975, long before Dylan’s fallow years of the ’80s began, the release of a new Dylan album was still ’cause for everything else to go into suspended animation. A new Dylan album? Are you fucking kidding? Stop the presses!

What I remember most about that first listen was “Idiot Wind.” The anger in Dylan’s voice. The fury. The way he lit into this woman who had somehow done him wrong. Or perhaps he was the one who had done something wrong, and now it was too late, and he was exorcising the anger he felt at himself. At the end of the song, he sang, “Idiot wind/ Blowing through the dust upon our shelves/ We’re idiots, babe/ It’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves.”

What I remember most about that first listen was “Idiot Wind.” The anger in Dylan’s voice. The fury. The way he lit into this woman who had somehow done him wrong. Or perhaps he was the one who had done something wrong, and now it was too late, and he was exorcising the anger he felt at himself. At the end of the song, he sang, “Idiot wind/ Blowing through the dust upon our shelves/ We’re idiots, babe/ It’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves.”

I was torn as I listened. On the one hand, I could dig the sarcastic “Like A Rolling Stone” vibe of “Idiot Wind” complete with swirling organ, but this wasn’t “Like A Rolling Stone.” The version of “Idiot Wind” on Blood On The Tracks was an echo of “Like A Rolling Stone.” I knew that, but I didn’t want to accept it. I tried to convince myself it was pretty great, but I couldn’t.

In those days I measured every new album from an artist I liked against their very best work. As I listened to Blood On The Tracks for the first time, I couldn’t accept that 1975 wasn’t 1965 and Dylan was a different person, in a different place, with different concerns. I wanted the angry, cynical rebel of the mid-’60s. I couldn’t accept that he’d grown up. I couldn’t accept his new album on its own merits. If it didn’t equal or top Highway 61 Revisited or Blonde On Blonde, it didn’t rate. That’s the way the young 21-year-old rock critic that was me thought in 1975.

There was another reason why an album that was mostly about a failed relationship did not click with me then. I had met a beautiful young woman, Leslie. We had kissed for the first time on New Year’s Eve, under the mistletoe as 1974 became 1975, and now I was spending most of my nights at the apartment in the Mission District she shared with two girlfriends. Romance was more than just in the air, and I couldn’t relate to the lost love Dylan was singing about on Blood On The Tracks. Not when I’d just found love.

It took years for me to appreciate how good the Blood On The Tracks songs are, that Dylan made a great album, and that he found his groove again. Still, there’s a reason I remember the afternoon when I first heard that album. What the weather was like. Where I was. Who I was with. Despite my denials at the time, on a deeper level that album meant a lot to me. I knew plenty about love gone wrong back then, I’d fucked up three previous relationships. I just didn’t want to think about it.

Blood On The Tracks, Redux

For a week now I have been listening to the new More Blood, More Tracks – The Bootleg Series Vol. 14 Deluxe Edition, six CDs that include nearly every recording made during the sessions that resulted in Blood On The Tracks. This is a remarkable collection of recordings – six hours worth. More Blood, More Tracks is of interest for a variety of reasons, not the least of which are the numerous standout tracks you will want to hear again and again.

As you may know, Dylan was having marital troubles at the time he wrote the songs for Blood On The Tracks. Though he has denied that the songs are personal, when Mary Travers (Peter, Paul and Mary) told him during a radio interview a month or so after it was released, how much she dug the album, he responded, “A lot of people tell me they enjoyed that album. It’s hard for me to relate to that—I mean, people enjoying that type of pain…” Dylan’s son Jacob later said, “…when I’m listening to Blood On The Tracks, that’s about my parents.”

Bob Dylan originally recorded the songs in New York during four days of intense sessions (September 16-19, 1974), mostly recording solo or with only bass player Tony Brown (and on a few takes keyboardist Paul Griffin), but on four songs backed by Eric Weissberg and Deliverance (“Dueling Banjos”). Dylan picked his favorite takes – a total of ten songs – and Columbia prepared to release them as Blood On The Tracks.

Dylan had second thoughts. So with the help of his bother David, he recorded in Minneapolis for two days (December 27 and 30, 1974) with local musicians and replaced five of the New York tracks (“Tangled Up In Blue,” “Idiot Wind,” “You’re a Big Girl Now” “Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts” and “If You See Her, Say Hello”) with the new recordings. Why? Perhaps some of those New York versions were too intimate. Dylan himself, interviewed by Cameron Crowe for the liner notes to Biograph, said, “The record still hadn’t come out and I put it [the acetate] on. I thought the songs could have sounded different, better, so I went in and rerecorded them.”

Listening now in chronological order to the over 86 takes (some partial, most complete), it’s clear that Dylan really was in top form for the sessions. What we get is a window into the whole of what Dylan was up to. What is most striking is his voice, and how beautiful/heartbreaking his delivery is time and time again. No matter how many times he records a particular song, each vocal is unique in often subtle, but sometimes dramatic ways.

Rather than a blow-by-blow of the 86 recordings, I will tell you about one song, a song first recorded on September 17, 1974, the first day of the sessions. It was only the fourth recording Dylan made that day. It’s the second take of “You’re a Big Girl Now,” and it’s exquisite. Dylan’s voice conveys his enduring love for this woman who has left him. She’s gone and he so feels the pain of that loss. Accompanying himself on guitar and harp, Dylan starts the second take with an intimate, somber delivery of the first two lines, “Our conversation, was short and sweet/ It nearly swept me, off of my feet.” The slight sad tremolo in his voice, “And I’m back in the rain.” What comes next is pure anguish as he sings “ooh ooh.” His heart is broken and it breaks yours to hear it. “You are on dry…” and he stretches out “la-and,” and then “mmm mmm, you made it there somehow.” A pause for some guitar, and his conclusion, “You’re a big girl now.” He stands in the rain, and he’s not on dry land; he’s a wreck. From his vantage point his former lover has survived this emotional storm, she’s moved on with her life, and left him to try but fail to pull himself together. All of that in just the first 37 seconds of a nearly five minute take.

The gap between the greatness of this sparse solo recording, which for me is a highlight of the set, and the version recorded in Minneapolis on December 24, 1994, three months later, that was included on Blood On The Tracks, is wide as the Grand Canyon. Here Dylan’s emotion is alive in every word. The fuller instrumentation on the version that was used on the album strikes me now as musical clutter, but it doesn’t hide the emotional remove in Dylan’s strained vocal. By the time he recorded “You’re a Big Girl Now” in Minneapolis, it was just a song, and not his life.

And that’s how it goes throughout the six CDs. Some recordings are better than others, all are worth hearing, and most, surprise surprise, are pretty damn great.

And about that young woman, Leslie, that I kissed with a passion that surprised us both that New Year’s Eve so long ago. We married in January 1976 and honeymooned in Oaxaca, Mexico; 42 years later we’re still together. To quote from a different kind of Dylan song than appears on More Blood, More Tracks, a song from John Wesley Harding: “Down along the cove/ We walked together hand in hand/ Everybody watchin’ us go by/ Knows we’re in love, yes, and they understand.”

Michael Goldberg was the founder of Addicted To Noise and is the author of The Flowers Lied (The Freak Scene Trilogy). He has also contributed two chapters to the recent book Kerouac On Record, including ‘Bob Dylan’s Beat Visions (Sonic Poetry)’.

You can also read this article, along with more than 50 other albums reviews in the latest edition of Rhythms magazine. Subscribe here: https://rhythms.com.au/subscribe/