Reviewed by Des Cowley.

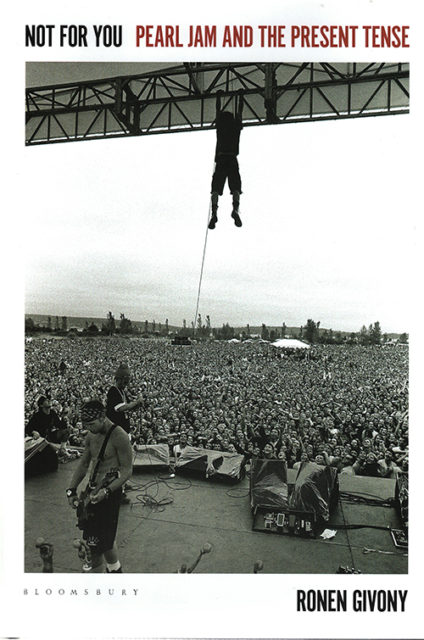

Not for You: Pearl Jam and the Present Tense By Ronen Givony (Bloomsbury)

A few years back, author Ronen Givony was commissioned to write a small book for Bloomsbury’s 33 1/3 series. This was an adventurous series, at last count running to almost 150 titles, giving writers free rein to flex their collective muscle by writing about an album of choice, one that presumably meant something to them. The series’ strong-suit – like Fight Club – was that there were no rules, writers were free to adopt any approach they liked, even stream-of-consciousness fiction, as they effectively descended down the rabbit-hole of obsession and fandom. Givony chose Jawbreaker’s 24 Hour Revenge Therapy, an obscure album by a punk band that, in his own words, “no one had heard of”. Reflecting back on the writing experience, he remembers: “the task had pretty much broken me”.

It borders on inspirational, then, to see that Givony is back for more – way more – in this hefty tome on grunge rockers Pearl Jam. Why Pearl Jam? That’s a question Givony expends plenty of words coming to grips with. Ok, he’s seen the band fifty-seven times, which seems not bad going, but this is a band that inspires genuine devotion among its fans. Givony is the first to call into question his own dedication: “There are people who would scoff at you for presuming to write a book after fifty-seven shows; and I don’t disagree”. If his book has a raison d’etre, it is to plumb his own fraught relationship to this music. Is it just a guilty pleasure? Is it simply a case of nineties nostalgia? Why is he happy to tell friends about seeing Radiohead two nights in a row, but not Pearl Jam? And right here is the rub: “Is Pearl Jam even any good?”

Givony’s book is not your standard biography of a band. For that, you’d need to look elsewhere (though there are surprisingly few books on Pearl Jam, especially in comparison to Nirvana). He has made no effort to interview band members, producers or roadies. He doesn’t take us into the studio when classic albums are being recorded. Instead, he’s gone where few would dare to tread – the dark web of Pearl Jam fandom. Is there a more bootlegged band, aside from the Grateful Dead? Early on, Pearl Jam encouraged fans to tape or film performances, with the result that there are few concerts that can’t be tracked down in some form. In the first two years of the new millennium alone, Pearl Jam released seventy-two official bootlegs of live material, each one a double-CD. That’s a lot of music to wade through. Thankfully for the rest of us, Givony is there to do just that.

Early on, Givony alludes to, without naming, Frederick Exley’s 1968 fictional memoir A Fan’s Notes. It could have been his own title. But how does one harness this vast amount of data and reconfigure it into digestible form? Givony finds inspiration in Ingmar Bergman’s film Scenes from a Marriage. What if, rather than attempting the totality, he instead breaks down Pearl Jam’s career into thirty stand-alone scenes, chronologically ordered, that might stand in for the whole? Key performances, recordings, events, big or small, the detail of which sheds light on the wider story. Some are unavoidable, like beacons on the landscape: the controversial video for early single ‘Jeremy’; the very public spat with Ticketmaster that kept the band off the road for several years in the nineties, and probably cost them a few albums; the disastrous Roskilde Music Festival in Denmark in 2000, at which nine young people were crushed to death near the stage; the band’s musical debt to The Who; or Eddie Vedder’s politics, right down to his invitation to the White House to meet with Bill.

Like punk, grunge music was a short-lived phenomenon, roughly lasting from 1991 to 1994, the year of Kurt Cobain’s death. After that, the energy began to flag, as lesser clones, like Bush or Creed, flooded the space, diluting the mix. For Givony, Pearl Jam’s years of greatness spans the nineties, incorporating an unbroken run of best-selling albums from Ten to Yield. Record companies today could only dream of such sales figures, with Vitalogy shifting 877,000 copies in its first week alone. Their initial rise was meteoric, going from playing small barns to stadiums in that first year alone. Rolling Stone magazine went as far as to say that if they broke up after their first album, which has sold some twenty million copies to date, their place in history would be secured.

The strength of Givony’s book lies in his readiness to make the tough call. His book is unreservedly opinionated, as so few these days are. Contrary to most PJ punters, he has no hesitation in citing No Code as their greatest album (strangely, I find myself concurring). He is kept awake at night worrying about whether Dave Abbruzzese, unceremoniously sacked in 1994, was truly the band’s best drummer. Givony proves himself a master of the bon mot, the memorable soundbite, demonstrating ample literary chops throughout. If I had room, I’d quote a hundred worthy passages. But all this outpouring comes with its downsides, not least of which is Givony’s tendency to quote Eddie Vedder’s onstage rambles verbatim, which can be dispiriting. His book is like a vast patchwork, a disassembled jigsaw. I came away thinking that perhaps it’s a book best dived into, like one of Eddie’s epic stage dives into the mosh pit, rather than studiously read cover to cover. His book, in a nutshell, proves both exhaustive and exhausting.

Thirty years on, Pearl Jam are still a going concern, having released their latest offering Gigaton early this year. Like the Rolling Stones, they long ago forfeited being a studio band, instead morphing into a live juggernaut still capable of selling out stadiums. Givony’s book understandably focuses on their first great decade, despatching the past twenty years in a few brief chapters.

By the end of all this soul-searching, what has Givony learnt? He certainly makes peace with his love of the band, though he remains unsure about their place in musical history.

Do they belong to the middle-brow bands of the early nineties (Smashing Pumpkins, Red Hot Chilli Peppers) or to the more credible, chameleonic types (Nine Inch Nails, Rage Against the Machine)? Their catalogue, he acknowledges, provides ammunition for both arguments. More fundamentally he recognizes that, in the intervening years since he first fell in love with Pearl Jam’s music, something essential has been lost to us: “It’s not just that album sales are down – but the very idea that an artist can bring people together – that’s increasingly extinct. Popular music was once a utopian, promethean, idealistic reaching-out. Today – like so much else – it is a retreat to our respective corners: an industry of spectators, algorithms, consumers and playlists”.

In publicly professing his continued love of Pearl Jam, Givony has chosen to side with the angels, holding steadfast to his belief in music as a unifying force.